Saving Historic Radio Before It’s Too Late

A first of its kind Library of Congress project aims to identify, catalogue, and preserve America’s rapidly deteriorating broadcast history.

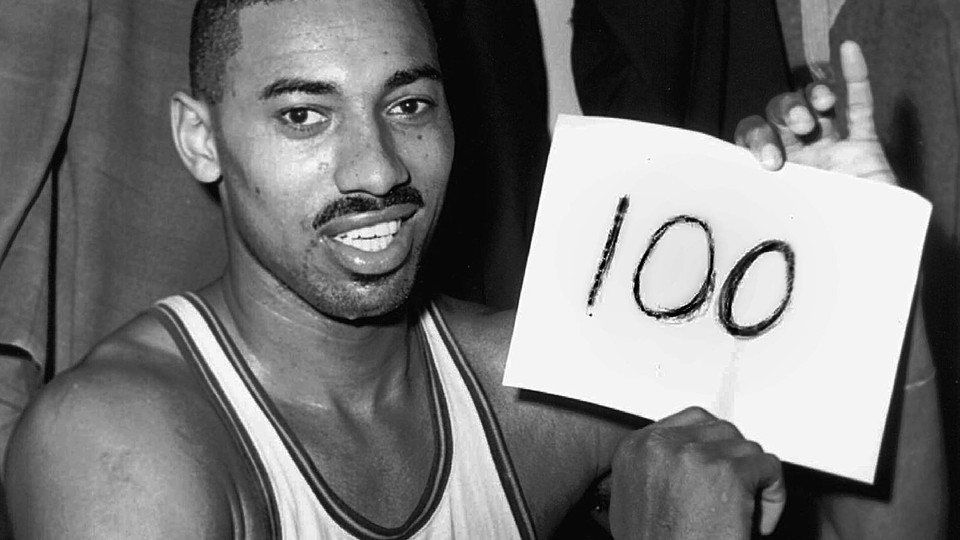

It was the most amazing scoring performance in the history of the professional basketball. So remarkable, in fact, that conspiracy theorists have floated the idea that it never happened at all.

On March 2, 1962, Wilt Chamberlain scored 100 points in a Philadelphia Warriors victory over the New York Knicks. No NBA player had ever achieved the feat, and none has repeated it since.

But you had to have been there to begin to understand how electric the atmosphere became in the Hershey Sports Arena, in Hershey, Pennsylvania, when Chamberlain set the record.

The game wasn’t televised. There is no known video footage of it. And newspaper accounts couldn’t do it justice.

The New York Times acknowledged Chamberlain’s performance was an “amazing feat,” but also understated what he’d accomplished, calling it “simply another plateau” for Chamberlain. Then again, the man himself downplayed his performance: “I was hot that night,” he said, according to the Times. “It was just one game.”

The most visceral artifact we have from that night is a short segment of audio: 36 seconds of a radio broadcast that includes the moment Chamberlain made it official. You can hear the whooping and whistling of thrilled fans spilling out onto the court. You can hear broadcaster, breathless, shouting over and over again, “He made it! He made it! He made it!”

And you can hear all this because, somewhere along the way, someone saved this little piece of audio history. Today, those 36 seconds were entered into the National Recording Registry at the Library of Congress.

Most radio isn’t so lucky.

Before radio came along, people thought the telephone might be the world’s first major broadcast device. In 19th-century demonstrations of the telephone, orchestras played over the line. People speculated that concert halls and churches would some day be filled with telephones, rather than people—so audiences and congregations could stay home and listen to performances and Sunday services from the convenience of the receiver in their front parlor.

These early predictions got the technology wrong, but they anticipated a phenomenon that would define the 20th century: broadcasting.

The radio ushered in an era of mass communication. It was intimate, immediate, and transformative. “Perhaps no invention of modern times has delivered so much while initially promising so little,” wrote Guy Gugliotta for Discover magazine in 2007. In the early years of the 20th century, ham radio operators were everywhere. Science and technology magazines devoted huge sections of each issue to helping amateur broadcasters build their own radio sets. “You could just set up a transmitter and start broadcasting stuff,” Rick Ducey, formerly the head of research for the National Association of Broadcasters, told Gugliotta. “That’s all it took.” By the 1920s, the radio seemed unstoppable—with tens of thousands of new stations opening each month.

But serious discussion of how to preserve early audio collections, and what to preserve, didn’t really begin until the 1960s, by which point decades of historic audio had been lost, destroyed, or never recorded in the first place. And format changes over the years have forced preservationists to start anew every few decades.

There’s no way to quantify how much of broadcasting history has been lost, except to say that most of American radio will never be heard again. That is, many scholars argue, in large part the fault of the Telecommunications Act of 1996, which eliminated mandates for local ownership and led to major consolidations across the radio market. New ownership often meant the obliteration of recorded history. “They literally incinerated and trashed entire local collections,” said Josh Shepperd, the national research director of the Radio Preservation Task Force at the Library of Congress.

Last month, the Library of Congress hosted scholars from more than 100 museums, radio archives, and universities for a symposium on preserving the country’s radio heritage. The conference was organized in response to an earlier Library of Congress report, from 2013, that found a slew of interlocking issues that threatened the history of recorded sound. “Research concluded that many recordings of radio broadcasts were untraceable and numerous transcription discs of national and local broadcasts have been destroyed,” Library staffers wrote in a statement. “Little is known of what still exists, where it is stored, and in what condition.”

Archivists know at least part of what has to be done, but that doesn’t make this task easy. In what the Library of Congress is billing the largest digital humanities and history initiative in the discipline of film and media, the Radio Preservation Project seeks to identify, catalogue, and preserve a gargantuan—and, for now, disparate—collection of noncommercial radio recordings in the United States. Ultimately, the plan is to create a massive searchable database of sound that anyone can use to hear the past. Some of those moments are historic in the traditional sense, in that they’re audio records of significant events: The 1936 Olympics in Berlin, believed to be the most widely recorded global event in the years leading up to World War II, for example, and a St. Louis radio station’s coverage of the first post-prohibition case of Budweiser leaving the factory (so it could be delivered to the White House).

But just as important is the identification and preservation of bits of radio that may, at first blush, seem ordinary. Mundane, even. “Radio was really primarily a history of public forums, interviews, discussions, and local histories—a lot of civil rights history, LGBT history, and feminism history,” Shepperd told me. “It was a way to communicate with [niche] communities, and it did not always leave paper trails. You had to be in a certain place at a certain time.”

Radio’s inherent ephemerality—especially long before the days of websites and podcasts—is part of the problem: Much of it wasn’t recorded in the first place. (That doesn’t mean audio produced in the Internet Age is safe from annihilation, however.)“Very little of it was saved, or it was lost,” Shepperd told me. Entire cultural narratives—radio history among indigenous communities, for example—have been nearly wiped out. The Radio Preservation Project will aim to find and save as much as possible of what remains.

Much of what’s already been lost will never be known to us. But scholars do have a wish list of radio that they’d like to find: Like tape from the Pittsburgh station KDKA, which aired presidential election returns in 1920—it represents one of the most prominent early news broadcasts—or audio from the 1925 Scopes Monkey Trial, one of the most significant court cases in American history and the first live radio broadcast of a criminal trial.

It seems unlikely that such tape will be found—recording equipment was still experimental in the 1920s—but discovering forgotten audio certainly isn’t, if you’ll excuse the pun, unheard of. One of my professors in graduate school once discovered a long-lost recording of the journalist Edward R. Murrow describing, in 1954, what it was like to fly into the eye of Hurricane Edna. It’s a lovely piece of tape.

In 2005, the sportswriter Gary Pomerantz went looking for people who had witnessed Wilt Chamberlain’s 100-point game. “At the outset of my research, I knew of one person at Chamberlain’s 100-point game: the Big Dipper himself,” he wrote. “Eventually, I interviewed 15 Knicks and Warriors players. I found the referee Pete D’Ambrosio, joking at 83, ‘You probably thought I was already dead, didn’t you?’” Pomerantz also tracked down Bill Campbell, the Philadelphia Warriors broadcaster who can be heard on the tape from that epic 1962 game, elated at what Chamberlain had achieved. Campbell was a man with a booming voice, “deep, full, and so smooth one listener was convinced he gargled with Turtle Wax,” Pomerantz wrote in his book, Wilt, 1962: The Night of 100 Points and the Dawn of a New Era.

By the time Chamberlain had notched 83 points, Campbell was ecstatic. “If you know anybody not listening, call them up,” he said. “A little history you are sitting in on tonight.” Pomerantz, in his book, paints a vivid picture of the scene that night—the carnival smell of chocolate, hot dogs, and popcorn, the thud of a leather basketball on “clicked-together maple hardwood,” and the smoke—from all the people smoking Lucky Strikes and Marlboros—wafting in the air.

But even this masterful description isn’t enough. You have to hear it. And, thankfully, you still can.