At the end of February last year, Bernard Turner, a 68-year-old former gamekeeper from Bodenham, Herefordshire, died of pneumonia. He had lived with multiple sclerosis for eight years, bedbound for five. Luckily – if anything still was lucky – he had his wife, Val, who not only loved him enough to be his full-time carer, but was also an experienced operating theatre nurse, then manager, who knew her way around patient care. They’d been married for 44 years by the time Bernard died, with Val beside him. He had never known that she was dying, too.

Two years earlier, Val had discovered a lump in her breast and guessed the worst. She had already seen her sister die of breast cancer, and knew that if she entered the world of scans and surgery and side-effects, she would have to stop caring for her husband – to say nothing of the sorrow, guilt and anger it might cause. So she did nothing, and the lump grew. She was 66 when Bernard died, and her own health fell apart more or less immediately afterwards. When the truth could no longer be hidden, she told it to her already grieving daughters, Julie and Clare. Ten days later, on 17 April 2015, Val Turner died, not two months after her husband.

“A work of art,” the music producer Tony Visconti called David Bowie’s death, but all except the very fastest and the slowest have to be. Along with the horror of a terminal diagnosis comes the obligation to choose who you tell, or don’t tell, as well as when you tell – and whatever you choose becomes a statement that will shape you in their memory. Not everybody wants to be remembered as a patient.

Leah Wilby, from Great Yarmouth, knew what it was like. She was only nine years old when she was diagnosed with neuroblastoma, a cancer of the nerve tissue. She was treated at Addenbrooke’s Hospital in Cambridge – she even gave the Queen a bouquet – and five years later she was in remission. Then the cancer returned, a week before Christmas 2009, and this time it could not be beaten. Wilby was a teenager by now, at a new school where her friends hadn’t known her as the girl with cancer, so she decided not to tell them. Instead she focused her last months on her GCSEs, even once she knew that she would probably not live for the results. Her treatment was arranged for the evenings so she would not miss school. She died, aged 15, on Monday 13 June 2011, and was buried in the prom dress that she never got to use.

An important distinction: privacy is what Wilby wanted, not secrecy, and what Bowie did too. It would be hard to imagine two more different cases, yet it seems that all either of them wanted in their final days was to carry on living. Bowie’s fans, like Wilby’s classmates, were shocked when they heard the news, but what could they have given David and Leah if they had known? Not normality, that’s for sure. Bowie’s cremation without a funeral shortly after dying, if that’s what happened, seems a clever way to keep his family from the same glare.

Canny to the end, Jackie Collins did something similar, telling no one but her three daughters about her breast cancer for more than six years. A few weeks before the end, she told others close to her, including her sister Joan. Finally, with six days left, she announced everything in an interview with People magazine, achieving maximum exposure for her final message: get yourself checked.

“It’s actually more common than you might imagine,” says Jayne Molyneux, a nurse who helps people manage prolonged conditions as a clinical change manager at Bupa. “We find that when people are first diagnosed they’re more likely to keep it to themselves initially … Often people need to think through their condition themselves, and then, when they’re feeling in more control, have that sense of control about sharing.” As a result, though every case is different, news of a terminal illness tends to move outwards, layer by layer, as each shocked group feels strong enough to tell the next, as the end gets closer, as the evidence gets harder not to see.

Whether or not the patient tells their family or friends, Molyneux would certainly encourage talking to someone. Often people who are seriously ill worry about the effect on their work, although they needn’t, technically. It is unlawful for an employer to sack you because of your health. Indeed, under the Equalities Act 2010, they are required to make any reasonable changes to your workplace or conditions that may help you do your job. Nevertheless, people worry about subtle shifts in attitude, or maybe a weird reluctance among clients and colleagues to commit to anything longterm.

That was Nora Ephron’s fear, or one of them. The writer, director and screenwriter was apparently worried that no one in Hollywood would back her projects if they knew she had myeloid leukemia. For six-and-a-half years she lived with the diagnosis, telling almost no one but immediate family. When she died in June 2012, having seemed so healthy to her many friends, it was a profound shock.

A sharp wit, a snappy dresser and a controlling character – though much-loved – Ephron’s approach to dying, like Bowie’s, was carefully thought through. In 2010 she published a book, I Remember Nothing, which now looks like a farewell. (For instance, it ends with lists of the things she will and won’t “miss”, and offers acknowledgements to “my doctors”.) She also left precise plans for a memorial service, even specifying friends who did not know that she was ill to give the eulogies. “She really did catch us napping,” Meryl Streep said, when her turn came. “She pulled a fast one on all of us. And it’s really stupid to be mad at somebody who died, but somehow I have managed it.” Being chosen made Streep feel “so privileged and so pissed off and so honoured and so inept all at the same time that I can’t help thinking that this is exactly what she intended”.

There is a hard question implied here. A few people asked it about Ephron. When you’re dying, how selfish do you get to be? Obviously you are entitled to choose what you want, and to get cut some slack, but you can’t take away your bereaved friends’ entitlement to be annoyed with you. As Molyneux has seen for herself, people kept in the dark, then left behind, have a lot to grapple with. “They wonder: why wasn’t I told? I wish I could have helped. I could have done more if only I’d known. We could have got something sorted out. I would have been there more. There are all of those questions,” she says.

The columnist Frank Rich was a close friend of Ephron’s for many years, and found himself among those who were “pissed off at first”. “Nora exemplified self-awareness and truth-telling,” he wrote in New York magazine. “Her choice to keep her illness a secret was not just out of character, but a Herculean task … What was she telling us by making her final chapter a secret? What, if anything, was she telling us about ourselves?” Like so many of Bowie’s friends did this week, Rich found himself sent off in search of clues. He went back through Ephron’s books (and found the last pages of I Remember Nothing). He replayed and re-evaluated his memories. He re-read her old emails. Had she meant to set a puzzle for him or Streep or any of the others? That was the puzzle itself. It’s the kind of thing you can’t stop wondering about. Mystery is the enemy of closure.

Not everyone agrees. Ephron’s son Max said in his address at her memorial: “I think that she just kept quiet so the rest of us could keep enjoying being with her as much as possible.” Had he known, he said, “All of those moments would have been bittersweet or sanctimonious … I am so glad they weren’t that way.” Compare this with the Australian journalist Amanda Platell, whose older brother Michael died of lung cancer, aged just 40, without telling many of his other friends or family that he was even ill. Writing about it in the Daily Mail, Platell gave thanks for the “precious times, a chance to say the things you should, but never do”. She is glad she had “plenty of time to remember – and to talk … I don’t think I would ever have forgiven Michael if he had not told me until the end”. These are – let’s say it again – different cases, but maybe those left behind need to find a way to be glad about whatever happened, in order to move on.

Dike Omeje met Mike Garry in 1995 at a poetry slam, where they finished in first and second place. Garry’s mother, it turned out, had taught Omeje at school. They even lived in the same part of Manchester, and shared doctors and dentists. They became close friends. Over the next 12 years they saw each other often at poetry events, they spent time with each other’s families, and round each other’s houses. On Friday 12 January 2007, Omeje rang Garry and they arranged to meet. “We went down to this reading and afterwards we chatted,” Garry says. “I remember I had a Vespa. He said: ‘I’m going to get one of those, you know. I keep getting parking tickets, and it’ll save me the hassle.’ I also owed him some money and said I’d go to the cashpoint and get it. He said: ‘Don’t worry. Get me on Monday.’ Then he went home and died.”

Omeje had a type of lymphatic cancer. He’d had it for 18 years, according to Garry, spanning the entire period of their friendship, and he never said a word. He did not tell his family, and only told “two or three” friends when circumstances forced it. He refused all medical treatment, which doctors offered with increasing desperation. Garry believes that Omeje hoped to survive the disease through a combination of healthy living and meditation. Instead, he died alone in his flat, aged 34, that Friday night. It was Sunday by the time he was found.

Like Ephron’s, some of Omeje’s friends were initially angry. Like Rich, Garry found himself hunting compulsively for clues to his dying friend’s thoughts and feelings. There was that time Omeje refused to give a blood sample at a sickle-cell anaemia event – most unlike him. There were those casual mentions of being so tired that he fell asleep at the wheel. Garry has since seen his own mother die of cancer, and now speaks admiringly of Omeje’s “honour”. “If I get cancer I’m not telling no one, I’m just disappearing,” he says. “I’m not putting people through the slow, drawn-out inevitability of death.” On the other hand, moments later: “Even after nine years, I’m still not right with it. I still find it hard to come to terms with his loss.” Might his friend’s secrecy be behind that? “You might well be right. I’ll sit here and I’ll say he did the right thing, but I’m still deeply affected by the death of Dike. I think about him all the time.” We can only guess how those “two or three” who kept the secret must be feeling.

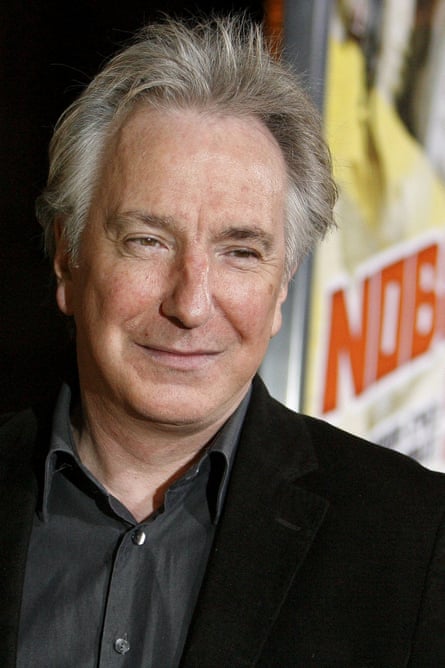

Omeje’s decision was at the extreme private end of a scale that is longer than it used to be. Alan Rickman’s illness was neither publicised nor, it seems, zealously hidden. Iain Banks announced his on his own website in April 2013, a month after he found out about it, and two before he died. Terry Pratchett invented a new career for himself as a right-to-die campaigner, following his diagnosis with Alzheimer’s. In October, Victoria Derbyshire broadcast a video diary of herself from her hospital bed following a mastectomy. Indeed, the cancer diary, once a shockingly raw novelty in the newspapers, is now a genre, with its own stars such as Stephen Sutton, and with old masters such as Clive James and Jenny Diski. (They “still battle it out for third place”, Diski wrote in November, following the deaths of Oliver Sacks and Henning Mankell.) Among such openness, is it now privacy that shocks? Does shocking people matter? That’s for the dying to decide.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion