Mexico City: measuring air quality and the spread of disease

There is no better example of a city turning things around – and quickly, said Seth Schultz, director of research, measurement and planning at C40 Cities. “It was not long ago that Mexico City held the dubious distinction of [being] the city with the world’s dirtiest air. That is no longer the case.”

A monitoring network to measure air quality, alongside new policies, have led to a reduction in persistent pollutants. The project is lauded as “one of the most successful and long-lasting health protection programmes in Mexico,” said Schultz.

Mexico City, which is susceptible to the spread of disease in hot weather, has also worked to improve its epidemiological monitoring during summers. Schultz said: “This has helped the city to uncover a major cause of gastrointestinal sickness: street food that is inadequately preserved during periods of warmer temperatures. The city has recently increased its prevention actions during heat waves to reduce the spread of these germs, especially among the elderly.”

Copenhagen, Denmark: calculating the power of the bike

For Charlotte Ersboll, corporate vice president of corporate stakeholder engagement at Novo Nordisk, Copenhagen stands out as a one of the best cities to move around in. “There are more bikes than citizens, and cyclists in Copenhagen collectively cycle 31 times around the world each day,” she said. “And it’s safe because of the bike lanes.”

Another key factor to the city’s success is that responsibility for public health is shared by all city administrations, said Victoria Pinoncely, research officer at UK planning body RTPI and author of a research paper on promoting healthy cities.

Copenhagener Esben Alslund-Lanthén, research analyst at thinktank Sustainia, agreed that decisions about cities should be made from a “holistic societal point of view”. This includes measuring health outcomes. “For instance, Copenhagen has found out that one mile on a bike is worth an economic gain to society of $0.42 [27p], while one mile driving is a $0.20 loss. This is the kind of calculation that is needed to build momentum towards more sustainable cities,” he said.

Chennai, India: rethinking the transport budget

“With more than 10,000 traffic crashes reported every year, the city has one of the highest rates of road deaths in India,” said Sustainia’s Alslund-Lanthén. But in 2012, Chennai implemented a policy that requires 60% of the city’s transport budget to be spent on infrastructure for pedestrians and cyclists.

Plymouth, UK: smashing down silos

“We are very much used to talking and thinking in silos, where food is one silo, workplaces are one silo, cities another and health is the healthcare sector,” said Alslund-Lanthén. He added that if all organisations were to integrate health into their practices, there would be greater workplace productivity, better performance in schools and more sustainable cities.

Things are starting to get better. Pinoncely, of RTPI, said many UK local authorities have started working alongside planning and public health teams. “For instance in Plymouth, a place-based, integrated approach to planning, health and social care is being implemented.”

Atlanta, US: partnering up

This city suffers from urban sprawl, traffic pollution and high rates of childhood asthma, said Behrooz Behbod, founder of Oxford Public Health. But he pointed to the Atlanta BeltLine, a city-wide redevelopment programme that is highly successful because has gained “the community’s engagement in all aspects of its design and implementation”.

The programme, a collaboration between various bodies in planning, health, transport, housing and elsewhere, could provide inspiration for many organisations that find it difficult to partner up. “Everyone wants to partner in theory,” said Chrissie Juliano, director of the Big Cities Health Coalition. “Some need incentives to pick up the phone and find a colleague in another agency. Some are worried they won’t understand ‘a different language’ in trying to problem-solve in a multi-sector way. Success stories need to be shared more broadly.”

Johanna Ralston, chief executive of the World Heart Federation, agreed that it can be difficult to get organisations and individuals in the same room. “Co-creation plays a role – getting everyone involved. [It’s] not easy, but bring a few sceptics inside the tent,” she said.

Belfast, Northern Ireland: involving the community

“We need to actively involve communities if we want to create better environments,” said Pinoncely, pointing to Belfast. The city encourages planners to engage with communities during the planning process, provides children with an opportunity to express views about how their environment impacts on their health, and gets older people to assess the walkability of the city, she said.

James Thornton, environmental lawyer and founding CEO of ClientEarth, agreed that citizen buy-in is a key element to creating healthier cities. “And how does the normal citizen get motivated? A lot of it has to do with the press, and making information available.”

Philadelphia, US: creating an active environment

The public health department in Philadelphia launched Get Healthy Philly in 2010, a project to promote healthy eating and create an active and smoke-free environment. “Its activities have contributed to real decreases in obesity among youth of colour,” said Chrissie Juliano, director of the Big Cities Health Coalition.

Cities should be designed to incorporate physical activity, and provide access to healthy food, positive social contact and contact with nature, according to Rachel Toms, lead on the Design Council’s Active by Design programme. “Every person needs these functions for their physical and mental health,” she said.

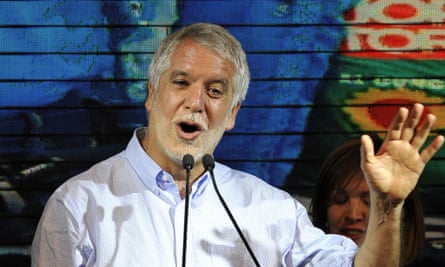

Bogotá, Colombia: leadership at every level

Leadership is crucial to getting health initiatives off the ground – whether it’s political leadership or comes from within the community, said Juliano. RTPI’s Pinoncely pointed out that Bogotá managed to implement many positive changes because of the leadership of Enrique Peñalosa, mayor of the city from 1998 to 2001. He has just been re-elected for the 2016-19 term.

Effective leadership needs to be broad enough to affect wide policy, according to Leo Hollis, author of Cities Are Good For You: The Genius of the Metropolis. He said: “Peñalosa was a good example of that, although he benefited from inheriting the job from Antanas Mockus, who should not be forgotten as a social pioneer. Can ground-up, local or neighbourhood pressure make a difference?”

San Francisco, US: preparing for climate change

San Francisco is linking health and climate change impacts together under one programme, which aims to educate and empower citizens and improve the resilience of public agencies, said Alslund-Lanthén. The city is using data and health indicators to inform climate adaptation plans and policies.

However, Hollis argued that its planning framework is incredibly confusing. “How can one have a progressive health and resilience planning structure when there is such a problem with gentrification?” he said. “Resilience cannot just be data-driven, or designed. If the social fabric is under threat, resilience is impossible.”

These comments were made during a livechat about how to create healthier cities.

Talk to us on Twitter via @Guardianpublic and sign up for your free weekly Guardian Public Leaders newsletter with news and analysis sent direct to you every Thursday.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion