On September 13, 2001, four US Senators from both sides of the aisle introduced the first version of the USA Patriot Act, a sweeping, 342-page bill that overturned virtually all US privacy laws and led to the creation of the global, pervasive surveillance programs that Edward Snowden disclosed in June 2013.

It’s possible that four senators and their respective staffers wrote the Patriot Act in a mere 36 hours, while America went into a panic over the worst terrorist attacks in US history. It seems a lot more likely, though, that the Patriot Act was already sitting in someone’s desk-drawer, waiting to be tabled when a suitable disaster occurred.

The conspiracy-minded point to Patriot’s swift introduction as evidence that 9/11 was an inside job, and that Patriot was just part of the plan. I think this is pretty implausible, and not merely because I don’t think that the parties involved would be depraved enough as to commit those atrocities, nor smart enough to get away with it.

A much more plausible explanation is that these surveillance-minded authoritarian political operators predicted that eventually something would happen, something big and terrible and eye-catching, and that this would create an opportunity to ram through their agenda. It was opportunism, not mass-murder. It’s not far-fetched: just last week, a leaked email from the General Counsel of the US Office of the Director of National Intelligence revealed that America’s spooks had decided to withdraw their calls for a ban on cryptography, but planned to reintroduce them after the next terrorist disaster had put Americans in a receptive frame of mind.

The goal of using disasters to seize power is terrible, but the tactic of thinking through the political possibilities of future events is fundamentally sound.

There will be terrorist attacks in the future – rare, overblown, and showy, but they’ll occur, because all you need to make a showy terrorist attack is a couple of idiots with bad ideas, and there’s a bottomless supply of both. Doubtless, there are authoritarians writing sequels to the Patriot Act to produce when the next atrocity strikes.

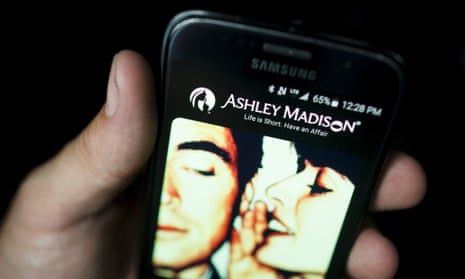

If the odd future terrorist attack is likely, then grotesque, cataclysmic privacy breaches are sure bets. The big breaches of the past year like Ashley Madison and the Office of Personnel Management, were so noteworthy that they crowded out the drumbeat of unimaginably terrible credit-card breaches at the likes of Hilton and Walmart and Target and literally dozens of other major companies.

What does this mean for privacy advocates? Since the internet’s inception, electronic privacy advocates have tried (mostly in vain) to convince people that they need to take online privacy seriously. From now on, we’ll get the hardest part of our job done for us, for free, by criminals and big, stupid companies and incompetent regulators.

Why did we suck at convincing people to care about privacy? Maybe because it was impossible. Humans are really bad at training their intuition to correctly assess propositions whose cause and effect are separated by vast expanses of time and space. The privacy disclosure you make today might never bite you in the ass, or it might come back to haunt you in ten years. When it does, you won’t be able to recall the thought process that you went through when you gave out that data today, and you won’t be able to learn any real lessons that will help you get better at disclosure tomorrow.

But now the privacy breaches and their consequences are coming in fast and furious. Ashley Madison and OPM were tremors, not quakes. There are bigger, scarier databases with more info on more people, and they aren’t any better (or worse) protected than any of the ruptured databases we’ve seen this year. The only way to be sure you don’t leak data is to not collect or retain it, and Big Data’s hype and the cheapness of hard drives has turned every pipsqueak tech company into a Big Data packrat with a mountain of potentially toxic personal info on millions of people, all protected by a password that’s simple enough for a CEO to remember it.

Every week or two, from now on, will see new privacy disasters, each worse than the last. Every week or two, from now on, will see millions of people who suddenly wish there was more they could do to protect their privacy.

For privacy advocates in 2015, the job is clear: have a plan in your drawer. A plan: how to safeguard your privacy, how to understand your privacy, how to understand the breach. A plan that explains that your lack of security isn’t a fact of nature, it’s the result of conscious decisions made by people who were either hostile or indifferent to your wellbeing, who saved or made money through those decisions. A plan that shows you what you can do to keep you and yours safe - and whose head your should be demanding on a pike.

We should still be advocating for better practices, businesses, technology and rules for privacy, but our job will be made simpler with an army of supporters. That army is ready to enlist, too, even if they don’t know it.

Yet.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion