Disruption and Desperation are Closer Than You Think

Some of the most iconic stories of disruption involve energetic entrepreneurs tinkering in their kitchen, garage, or at their computer. But disruption rarely starts that way.

Far more often, we wait to try something new (disruptive) until we’ve exhausted all the normal channels and nothing else has worked.

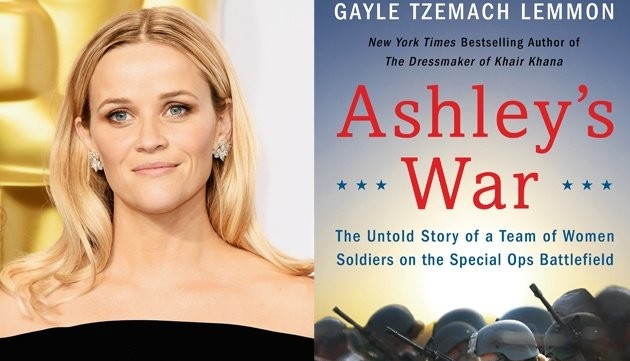

That’s what happened in Afghanistan. The U.S. was eight years into what had become the longest war in its history and it wasn’t “winning”. Desperate for any edge, military leaders ultimately started rethinking one of the fundamental rules of warfare: no women on the special operations frontlines. As vividly described in Gayle Tzemach Lemmon’s book Ashley’s War: the Untold Story a Team of Women Soldiers on the Special Ops Battlefield, the U.S. Special Operations Command eventually realized that they needed female soldiers to gain access to places and people that were out of reach, due to the strict gender rules of Afghan culture.

In Afghanistan, family is central, and women are the linchpins: they see, overhear and understand what is happening in their households. But if a foreign man speaks to an Afghan woman, let alone enters her quarters, he dishonors her and the men designated to protect her. As a consequence, male U.S. soldiers were forbidden to have any contact with Afghan women, leaving special operations often blind and deaf to half the population of Afghanistan. The U.S. desperately needed better intelligence to change the course of the war, so in 2010, the U.S. Army Special Operations Command (SOCOM) created Cultural Support Teams (CST), a group of handpicked women from across the Army who would be embedded with regular special ops (e.g. Army Rangers and Navy SEALs) teams.

Though officially banned from combat, these female soldiers could speak to and enter the rooms of Afghan women, hives of information hidden to the male soldiers. On a typical mission, a CST and an interpreter would go into Afghan homes at night, speak to the women and children, often protecting them from battle fire, while also ascertaining the identity and whereabouts of suspected insurgents.

A year into this pilot program, the head of SOCOM, Lt. General John Mulholland said, “These women have provided enormous operational success to us on the battlefield by virtue of their being able to contact half the population we don’t normally interact with.” Some aver that the success of these Cultural Support Teams provided the foundation for opening up all roles for women in special operations.

But the Army may not have changed its policies regarding women had circumstance not forced its hand. “Women eventually became part of the solution, because all the usual answers by this time had been attempted and found wanting. All anyone wanted at this point was people who could help accomplish the mission,” says Lemmon. Disruption was possible because of exhaustion, exasperation and stalemate.

Just because it was important to think outside the box to win the war doesn’t mean it wasn’t painful. The male soldiers needed the female soldiers, but that doesn’t mean they wanted them. As one trainer at Ft. Bragg said in trying to prepare the women for the internal cultural challenges ahead, “They [the male soldiers] are going to hate you and you have to be prepared for that.” Disruption is rarely painless. For any organization to remain vibrant, it needs fresh ideas, but those ideas often come with the price tag of engaging with people who are not like us and have conflicting views. The inevitable intellectual skirmish can call into question our feeling of belonging and insider status. In our desire to escape that psychic discomfort, we inadvertently label certain people and ideas as outsiders, rejecting the very resources that could help us get out of the box.

One important note about the decision to create these Special Ops roles for women: the Army didn’t have to find new recruits. The women they needed were already in Army – some serving as Military Police and intelligence officers -- or the National Guard – women who had been waiting and in many cases, wanting such an opportunity their entire lives. It was a simple matter of reassignment. It often happens that the talent you need for disruption is already within your organization.

Take for example, a large cardiology practice in northern Michigan. In order to be selected for absorption by a hospital corporation it needed to undergo a restructuring with an increased emphasis on customer service. Neither the physicians nor staff was customer-service or sales-driven. The practice administrator, for example, was an effective coder for insurance purposes, but wasn’t trained in running the front desk and writing thank-you notes. Nor could they hire a customer service manager due to a tight budget. As Wendy Lipton-Dibner, author of Focus on Impact, and her team worked to find a solution, they noticed how the doctors and staff displayed customer-friendly behavior on the personal front, from sending holiday cards to answering personal calls. As the twelve doctors and ninety staff members began to leverage what they already did personally, they were eventually able to divide amongst themselves the tasks that would have otherwise been done by (3) full-time customer service people – day, swing and night shifts– and their patients were better served.

Finding hidden or previously overlooked talent within your current staff can make disruptive ideas happen faster and at a much lower cost.

It’s a lot easier to come up with disruptive ideas if you’ve had some practice. U.S. Special Operations Commander Eric Olson was a highly decorated Navy SEAL. Special operations forces favor small units over large forces and independent problem solving over the formal, traditional military hierarchy. As a member of the elite forces, Olson had been disrupting his entire career. So when traditional tactics weren’t working in Afghanistan, Olson turned to his problem solving abilities. “Crucial information was hiding within a population to which special ops forces, nearly a decade into the war, had virtually no access: the women.” Because he was used to disrupting, Olson was able to see a solution that might have been unfathomable to someone embedded in lock-step tradition. If we are going to ride the waves of disruption, we need individuals inside of our organizations who can and will question the status quo, but also have the gravitas to get the answers.

In describing the evolution of the special operations forces, General Stanley McChrystal, sums it up with a business analogy: “We started the war as the greatest booksellers in the world and ended as Amazon.com. “ If you and your business have exhausted all possibilities, it may be time to step outside the box of tradition, to search out and find the resources already on hand. When you are driven to disrupt, you may just win the war. Or at least stop from losing it.

***

For more on this topic, see Tzemach Lemmon's excerpt on TED. For information on the film that will be produced by Reese Witherspoon, click here.

If you would like to receive updates on when I publish, including tips on personal disruption, sign up for my newsletter at whitneyjohnson.com. You can also pre-order my book "Disrupt Yourself: Putting the Power of Disruptive Innovation to Work" (release date: Oct. 6, 2015).

Athletic Intelligence Team

7yLena Salter

Columnist Contributor at BIZCATALYST 360

8yNice and worthy experiences to learn from

English -High School

8yWhat a wonderful article! Super excited to read the book and see the movie! I'm especially hopeful your move goes smoothly!

Payroll Manager

8yEnlightening. Thanks for sharing.