New Yorkers Have Been Illicitly Cracking Open Fire Hydrants For Centuries

Summer in New York. (Photo: Rebecca Wilson/flickr)

Summer in New York. (Photo: Rebecca Wilson/flickr)

It’s become a tradition for New York City reporters. The scene: a steamy day in July or August, heat distorting the air above a scorching pavement. People hold bottles of cold water or cans of soda to their foreheads. And some kids, or teens, crack open a city fire hydrant. The cool water is the block’s savior. Kids and adults alike dip their hands, feet, and faces into the gush of water. (Not coincidentally, these images and stories tend to come with a side dish of exoticization: It’s more likely to see a hydrant bursting in Bed-Stuy than the Upper West Side.)

For years, the city responded to reports of open fire hydrants with penalties, up to $1,000 fine or a 30-day sentence. It’s much the same in other cities with frequent recreational hydrant issues, from Chicago to, recently, Paris, where one video of Parisians opening a hydrant is accompanied by this commentary: “It seems the residents are copying this from what they see happens in American ghettos during hot weather.”

More recently, New York City has taken a harm-reduction approach, with substantial educational outreach programs to convince people not to open the hydrants themselves, but to allow a fireman to do it in a controlled manner. It’s much the same technique that some countries use for treating drug addiction: people are going to do this no matter what, so why not just ensure it’s done safely?

And it could be argued that another official city concession, way back in 1896, was responsible for starting this whole thing.

When a Hydrant Was Just a Hole

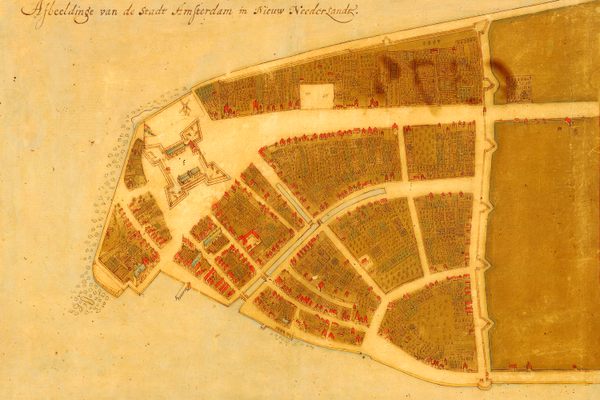

The earliest “hydrants” in New York City (dating back to the early 1700s but lasting until the late 1800s) were simply buckets of water scattered around the five boroughs, left locked by the fire department so as to keep out thieves and vandals. The next generation of devices, ones that tapped directly into city water mains, were a little bit more exclusive. According to the New York Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), the group responsible for maintaining hydrants, these early water taps were not so much hydrants as, well, holes.

Water mains, which were only accessible by the rich, ran in limited numbers underneath the city, made mostly of hollowed-out logs. If a fire department needed water, they’d drill a hole in the pipe, take what they needed, and then leave a cylindrical wooden “fireplug” in the hole they’d just made. (Most cities, including New York, had competing fire departments in the 1700s. Whoever actually put out the fire would get paid, so the departments would have their biggest, toughest guys guard their plugs to stop other companies from tapping their holes. That’s where the term “plug uglies” comes from.)

The first New York City fire hydrant, which differs from a fireplug in that it’s above-ground, was installed in 1808 at the corner of William and Liberty streets, far in the south of the island of Manhattan, near Wall Street. After 1808, the city began ramping up its water infrastructure and rapidly improving its hydrant technology.

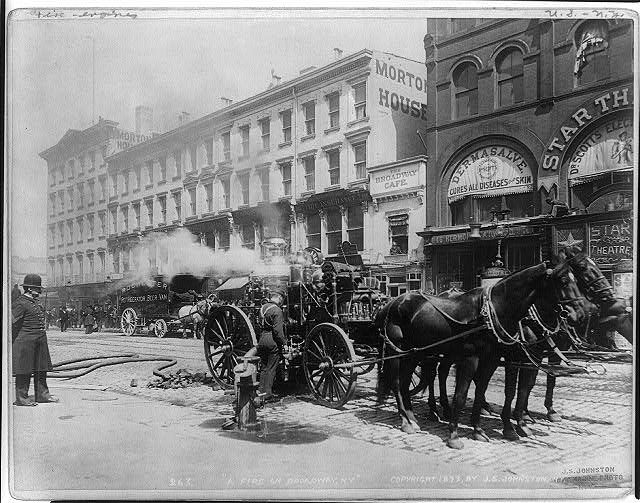

A fire on Broadway in 1893, with a hydrant in the foreground. (Photo: Library of Congress)

A fire on Broadway in 1893, with a hydrant in the foreground. (Photo: Library of Congress)

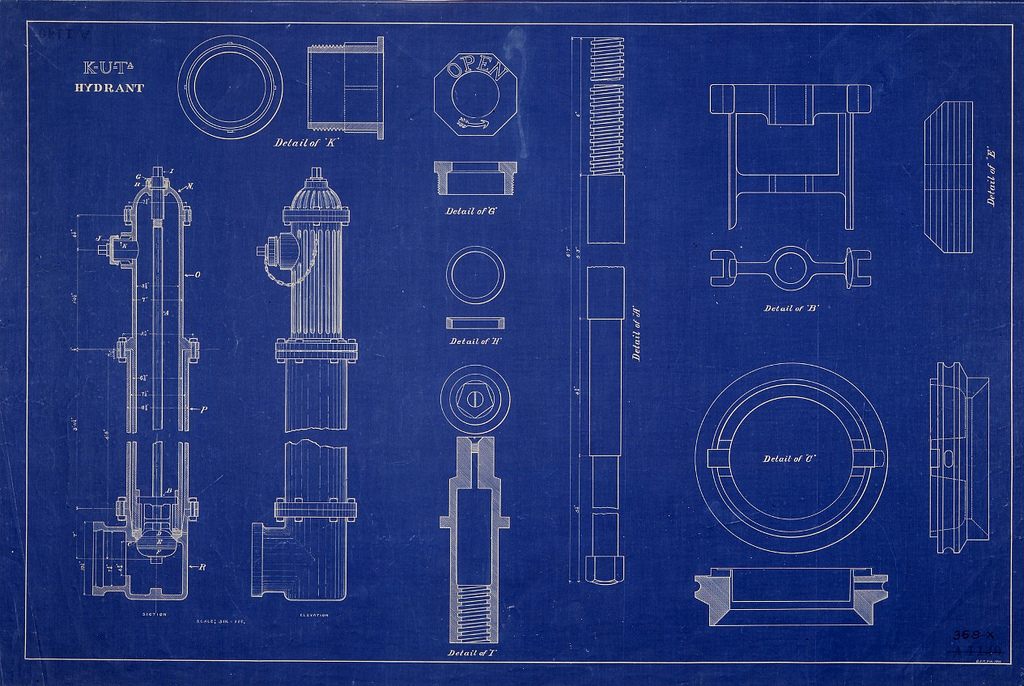

The first iron hydrant was installed in 1817, and in 1869, a New Yorker named Birdsill Holly patented a new kind of fire hydrant, one that could cope with the highly pressurized water system in New York City. Fire hydrant design hasn’t really changed since 1869; there are some different aesthetic looks, but their operation has remained fairly static. That may change, as fancy new designs for fire hydrants made of tougher materials that won’t freeze or crack in the winter have popped up. But the venerable iron hydrant remains the standard in New York. Today, New York City has about 109,000 fire hydrants.

The first mention I can find of people using New York City fire hydrants for recreation comes from Edward P. Kohn’s excellent nonfiction account of the disastrous 1896 heat wave, Hot Time in the Old Town. The 1896 heat wave is a relatively unknown but incredibly deadly natural disaster; about 1,500 people died, especially clustered in the cities of New York, Chicago, Boston, and Newark. “The concrete, brick, and stone of the buildings and the asphalt of the city’s streets can conduct heat three times faster than soil,” writes Kohn. (More detail here, if you’d like the science.) “Unlike the hills and trees of the countryside, urban walls, roofs, and streets act like a maze of reflectors, bouncing the heat back and forth between absorbing surfaces.” The most advanced temperature measurements at the time, which incorporated lack of wind and high humidity, pegged the temperature in the summer of 1896 at over 135 degrees Fahrenheit.

Worse, the conditions of the poor, especially in the tenements of lower Manhattan, were horrific. There wasn’t enough room for people in the best of times, and when temperatures indoors rose well above 100 degrees, staying indoors became intolerable, often deadly. People slept on roofs, on fire escapes, in the streets, on the piers. People swam in the rivers (which were not any more sanitary than they are now) and flooded Coney Island. Keep in mind that this was also a time when the vast majority of people had no refrigeration and no ice, let alone electric fans or air conditioning.

A blueprint from c.1906 showing cross-sections and designs for a fire hydrant. (Photo: NYC Water/Flickr)

A blueprint from c.1906 showing cross-sections and designs for a fire hydrant. (Photo: NYC Water/Flickr)

Eventually, with the death toll rising sharply, the police commissioner, a young Teddy Roosevelt, demanded (among other efforts like allowing people to sleep in parks) that the fire department plug into the fire hydrants in lower Manhattan and spray down the streets, cleaning off the garbage, filth, dead animals (many many horses were killed and left on the street if they got too hot), and various other horrible substances and smells that were plaguing the city. New Yorkers, enterprising as always, treated this like a water park. Writes Kohn, quoting a letter written by the head of the fire department at the time:

“It was a great boon to the poor people in the tenement district,” Collis wrote. “Parents literally brought their children in the street to have the water poured on them and there was at least 50,000 little ones to whom it was a perfect holiday. Many of the adult citizens thanked me and everybody seemed to think it was a good thing.”

Hot Times in the City

The first mention I can find in the New York Times archive of somebody cracking open a fire hydrant during New York’s brutal summers comes from May of 1904, with the headline “Busy Street Deluged: A Little Boy’s Prank.” Apparently some jerk of a kid used a big wrench to pry open a fire hydrant at 5th Avenue and 14th Street, where it drenched and outraged many New Yorkers.

By the 1930s, the practice of opening fire hydrants was common, and dangerous. It didn’t take much, at the time. Tools easily gotten from a hardware store or a garage could open one. (Specifics are being left out at the request of the New York Department of Environmental Protection; the techniques, like the hydrants themselves, remain largely effective to this day.) In the less affluent parts of the city, fire hydrants are a fantastically economical way to cool down.

By the late 20th century, opening a fire hydrant was almost a tradition. A scene from Spike Lee’s 1989 movie Do The Right Thing shows the preparation for a hydrant party during a Brooklyn heat wave. It’s easy enough to open a hydrant, but that’s not the end of the prep-work. Break off the top and bottom of a metal can, making a tube—you can use this to direct the water upwards, instead of merely down onto the street. These images, as much as a Nathan’s hot dog on the Coney Island boardwalk, signify New York City summer.

The water itself is even safer than eating a Nathan’s hot dog. A DEP representative confirmed to me that the water that comes from the hydrants is the exact same, legendarily high-quality, delicious water that gets piped into our faucets. The water spilled from a centuries-old iron hydrant in the Bronx is higher quality than the best tap water in all of Los Angeles. It’s not only fine to play in—it’s luxurious.

But that doesn’t mean the act of tapping a hydrant is safe. It’s wasteful, for one thing; the hydrants let loose with about a thousand gallons of water per minute, a figure sure to make any Californian very uncomfortable. It can cause a drop in water pressure throughout the neighborhood, which is annoying for neighbors and possibly dangerous for any fire department that needs to tap an adjacent hydrant. And there have been many instances of people, especially small kids, being slammed by the force of the water out into traffic, where they can be hurt or killed.

Playing with hydrant water in 1943. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Playing with hydrant water in 1943. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Since 2007, the New York City DEP has multiple programs to combat the illicit opening of the city’s hydrants. With very few exceptions (some hydrants, like in Breezy Point, Queens, are still privately owned, for some reason, and others are locked), you can go to pretty much any firehouse in the five boroughs and ask for a spray cap. The fire department will come to the hydrant of your choosing, open it up for about 12 hours, and install a cap that creates several thinner streams of water, like a giant lawn sprinkler. This cap uses only about 25 gallons of water per minute—still enough to be fun, but not enough to cause much damage or waste all that much water. And the DEP has a team called the Hydrant Education Action Team (HEAT), arrays of volunteer teens who go around their neighborhoods telling people about the dangers of opening hydrants and the benefits of spray caps.

The spray cap in action. (Photo: NYC Water/Flickr)

The spray cap in action. (Photo: NYC Water/Flickr)

This solution seems better than just criminalizing a hallowed tradition—but old habits die hard. As of July 6th of 2015, the DEP received 4,458 complaints of open fire hydrants, more than for the same period of either 2014 or 2013. If you still want to dabble in the dark arts of the open hydrant, all you have to do is look.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook