To Be Asked for a Kiss

Suicide’s Note

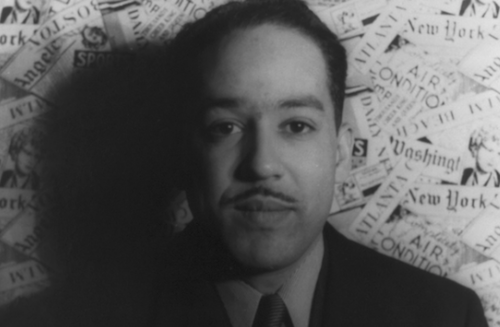

by Langston Hughes

The calm,

Cool face of the river

Asked me for a kiss.

The desire to be dead and the desire not to be alive and the desire to kill oneself are three different desires.

The desire to die is not the desire to be dead. Anyone who has ever been in love knows this.

And though all of these desires seem—to those who have never had them—synonymous with the desire to run away, they are not the desire to run away. Any look at the recent statistics on gay teen suicide is proof of this.

I am, because I’ve been assigned to think in this way about this poem, trying to remember the last time I wanted to kill myself. I don’t have to remember the last time I wanted to die because that would be as simple as remembering the last time I had sex without a condom.

When people ask me to examine a poem I love, they mean for me to dismantle the poem . . . to undress the one I love before them down to his linebreaks, his rhythms, his slick and sustained use of metaphor. They want to know why I love and how they should. They want love coming out of my mouth to be more mathematical than it is in their own lives.

“Suicide’s Note” is one sentence long. Counting its title, the poem is 14 words, 17 syllables, a single tercet.

Here, an audience would like for me to say a thing or two about haiku and its relationship to the blues stanza, but I’ll get to that later. Maybe.

Langston Hughes published “Suicide’s Note” in his first book, The Weary Blues, in 1926, which means he was less than 24 years old when he wrote it.

I don’t know whether or not Hughes ever considered suicide, and of course, I don’t think that matters.

Or do I?

I believe it matters that Langston Hughes was careful not to do anything to make us perceive him as someone capable of a negative thought. And so a star is born. And so black folk know the name of at least one black poet.

But none of that is my assignment.

I am to examine a poem I love. And examine means that you want, at least, to know what I think of the title.

“Suicide” is both a verb and a noun. The title of the poem and the lack of an article before the word “suicide” allows us to begin to think of the act as a being, a personage capable of writing something as thoughtful as a note.

If I had committed suicide when I was 12 or 14 or 16 or 18 or 20 or 22, I would not have left a note.

Now I remember. I was 22. Look at what writing can do. It can help me remember and to smile at Sexton’s “unnameable lust return[ing]” to me every other year for ten years.

Where was I?

The note.

The joy I had in thinking of how best to get rid of myself was always tied to inventing ways for it to seem an accident. What time is the bus that’s on time when I’m late and rushing across the street? Do I know anyone on the roof of a building I can help? How many pain pills is an accident?

I would not have left a note because the suicide is—believe it or not—the most competitive person in the world. I once understood death as a competition. I had to do it before anyone or anything else did it to me. I was interested in winning, and I was convinced that someone would interpret a note left behind as a letter of surrender.

The first line of the poem is end-stopped, marking the beginning of the speaker’s end. The break after “the calm”—such a truncated phrase—calls again to our understanding of a single word with two functions. If the title of the poem shows us some embodiment of the act of suicide, then the first line defines its outcome as “calm.”

Whenever I read a poem, I read for what it doesn’t say. In the church where I was raised, one of the things for which so many people publicly prayed every Sunday is peace. The calm of the suicide, like his note, is the dream of the speaker, the self he is after, the self that is not there.

Alliteration starts the second line, and we begin to understand “calm” more fully as an adjective and not only a noun.

Here comes the blues I was supposed to play earlier.

While the poem is not a blues poem in its form exactly, the second line fully positions it as a blues poem in its content. As in haiku, the blues stanza juxtaposes two seemingly different images or ideas or emotions in order to show the interrelatedness of the two.

In his 1926 essay, “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain,” Hughes calls the blues, “incongruous humor that so often . . . becomes ironic laughter mixed with tears.”

What is a “cool face?” If it is a face that expresses disapproval or the aloof nature of its owner, don’t we wonder why she is so mean and how we can please her? If it is a face in full confidence of its beauty or with features that attract us, don’t we want that face to look our way?

The alliteration of “calm” and “cool” in this poem ties me to its pull down toward its final piece of punctuation. And “the river” means to make that movement downward toward the end all the more gentle. Water quenches thirst. Water flows free.

Langston Hughes wrote what is probably his most famous poem, “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” when he was 18 years old.

He wrote about rivers until the end of his life. In some of the poems, they are sites for murder. In others, they are sites for suicide.

In Hughes’s poems where rivers are sites for suicide, the speaker is the victim of unrequited love.

Yes, we could drown in a river, but we could also drown in someone’s loving arms. Now doesn’t that sound like the blues?

The act of suicide as a personage is, in this poem, one with the river. It flows in one direction.

I don’t know why I stopped wanting to kill myself. I didn’t have a therapist. I didn’t take medication. I imagine I am the last of those raised by binary believers. To us, it was told that white people had few troubles, and they couldn’t deal with any of them without another bill to pay for anti-depressants or for someone to listen.

I am old enough to be of a generation of black people who didn’t think black people killed themselves. Adults would say as much.

When my lover cries about a black boy as far away from us as Johnson & Wales University in Providence, Rhode Island, hanging himself in his dorm room, my lover cries because nothing we heard adults say while we were young seems true.

Forty-three percent of black gay teens have contemplated or attempted suicide. My lover has never been to Rhode Island.

Alliteration moves to consonance and then back again to alliteration in the final line of the poem. Only now, the sound we’ve encountered by way of the letter “c” comes to us through the more definite letter “k.”

Africa. Afrika. Clan. Klan.

“K” is the first letter in the word “kindness.”

Suicide—“the calm, cool face of the river”—was kind enough to have “asked” the speaker. And for what?

Whenever I read a poem, I read for what it doesn’t say. The speaker—and this has a great deal to do with why I love this poem so much—is dead. He talks to me, to us, from the grave.

Even from the grave, he admits that all he ever wanted was to be asked for a kiss.

“Suicide’s Note” is not a poem about suicide. On the contrary, it is a poem about living forever. About finally getting what we want and getting it even after death.

The poem is interested in the immortality of poetry. The speaker doesn’t want to die as much as he wants to oblige. Who doesn’t want a kiss? Who doesn’t want a cool face to ask for that kiss?

I don’t remember why I stopped wanting to kill myself, but I do know how I stay alive. Though I love to kiss my lover, it is not because of his kisses. Though I am laid open when he cries, it is not because of his tears.

I live to write poems. And I write poems because it’s all I can do to stave off death, or as Sexton said before killing herself, “Suicide is, after all, the opposite of the poem.” After all.

Only poems allow me the opportunity, even when I get them wrong, to try at communicating with the dead and, hopefully, with those who have yet to live.

By the time I turned 22, I don’t know that I wanted to stay alive, but I did, and still do, want to write a poem.

Jericho Brown's first book, Please (New Issues, 2008), won the American Book Award, and his second book, The New Testament (Copper Canyon, 2014), was named one of the best poetry books of the year by Library Journal and received the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award. His third collection, The Tradition (Copper Canyon, 2019), won the Pulitzer Prize...

-

Related Authors

- See All Related Content