This week I have been thinking and reading about monocentric and polycentric cities. In urban real estate economics, the monocentric city model has historically been an important economic model. Developed in the 1960s, it attempts to explain land use in cities with one core, or central business district (CBD).

In its most simplest terms, the model states that as you move further away from that core, land prices will fall. But since retail and employment need to be at the center of large catchment areas, they will remain in the middle, while the residential will naturally spread out.

When you begin to factor in transportation costs, there is an argument to be made for why inner cities neighborhoods were often poorer in North American cities (no car; higher transportation costs) and why the suburbs were often wealthier. In this latter case, the rich wanted to consume more home/real estate and their transportation costs weren’t as significant. They had cars and subsidized highways in which to drive them on.

Of course, there are many ways in which you could argue against the above. Today, urban neighborhoods are some of the most desirable areas in many cities.

But perhaps the most obvious thing to question is the idea that cities only have one central business district. I mean, just look at all the employment nodes in Toronto. Yes, downtown Toronto is still the dominant zone, but could we really be considered monocentric?

From what I remember, the model had mechanisms for dealing with polycentricity. But at the same time, so much has changed since the 1960s. The central business district with its big department store was only just getting introduced to the likes of fully enclosed, climate-controlled suburban malls. And of course today, we are now living in a world of Amazon Prime and independent workers.

So what does this mean for cities?

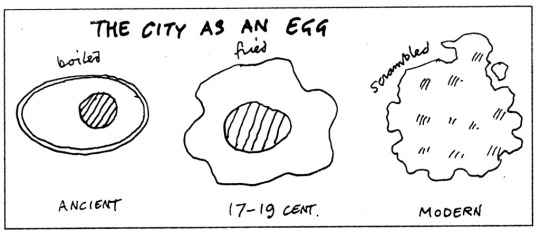

Well, as I was reading up on this topic I stumbled upon this diagram by architect Cedric Price (1934-2003):

I wish I knew exactly when this diagram was created, but I wasn’t able to find that online. In any event, the diagram uses different kinds of eggs – boiled, fried, and then scrambled – to explain the urban morphology of cities over time.

In the ancient world, cities had a clearly defined core and a clearly defined perimeter – often a wall for defence (boiled egg). In the 17-19th centuries, cities started to expand outwards through the advent of technologies like rail. This gave them a more irregular shape (fried egg). And then finally, Cedric argues that the modern city had, or would, become all mixed together like scrambled eggs.

I wouldn’t say that our cities have become completely scrambled. But I would agree that we are moving away from the simple fried egg of a city (or monocentric city model). So I guess the big question is really: How scrambled do you think we’ll get?

Pingback: Rightsizing in Kits Point | BRANDON DONNELLY