Mysterious structures found deep inside a French cave are the work of Neanderthal builders who lived in the region more than 100,000 years before modern humans set foot in Europe.

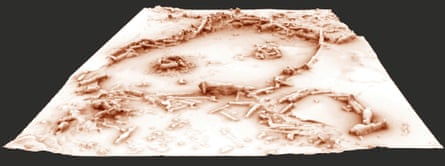

The extraordinary constructions are made from nearly 400 stalagmites that have been yanked from the ground and stacked on top of one another to produce rudimentary walls on the damp cave floor.

The most prominent formations are two ringed walls, built four layers deep in places, which appear to have been propped up with stalagmites wedged in place as vertical stays. The largest of the walls is nearly seven metres across and, where intact, stands up to 40cm high.

“This is completely different to anything we have seen before. I find it very mysterious,” said Marie Soressi, an archaeologist at Leiden University, who was not involved in the research. Unique in the history of Neanderthal achievements, the structures rank among the earliest human building projects ever discovered.

Parts of the walls show clear signs of fire damage, with the stalagmites blackened or reddened and fractured from the heat, leading researchers to suspect that the Neanderthals embedded fireplaces in the structures to illuminate the cave.

This article includes content provided by dailymotion. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. To view this content, click 'Allow and continue'.

Dotted around the construction site are round holes in the ground where the stalagmites were wrenched from the cave floor, demonstrating that builders have not cleared up after themselves since at least the Middle Pleistocene.

Local cavers happened on the mysterious formations in the 1990s, more than 300m from the entrance to the Bruniquel cave, near the Pyrénées mountains in southwest France. Back then, the stalagmite structures were assumed to be 50,000 years old, the same age as burnt animal remains found nearby.

But fresh tests on the structures, reported in the journal Nature, reveal the simple walls to be much older than thought. Stalagmite tips and pieces of charred bone found in the walls date them to at least 175,000 years ago. According to French and Belgian scientists who led the research, only Neanderthals could have built the structures. While bears in the cave left behind claw marks, paw prints, tufts of fur, and even hibernation holes, they were not able to stack stalagmites into foot-high walls, the researchers say.

Neanderthals lived in Eurasia from about 400,000 to 40,000 years ago and died out just as modern humans arrived in the region. Though often dismissed as thick-browed thugs, our human relatives were immensely capable, as evidenced by hauls of stone tools and other artefacts they left behind. The Neanderthals harnessed fire, lived in shelters, wore clothes, and mastered the art of stone tool making. Some researchers believe they deliberately buried their dead, and even adorned the graves with offerings such as flowers.

But that is not all. The Iberian Neanderthals had a fondness for sea shells, and turned scallop and cockle shells into jewellery by painting them with mineral pigments and probably threading them on strings. Other Neanderthals made artificial glue by careful burning of tree bark, to help fix their sharp stone tips to spear shafts.

For all the feats Neanderthals achieved, until now, building had never seemed one of their strong points. “Early Neanderthals were the only human population living in Europe during this period,” Jacques Jaubert at the University of Bordeaux writes in the journal, suggesting the early human species were even more sophisticated than even expert researchers appreciated.

The site is remarkably well preserved because the stalagmites became encased in calcium carbonate soon after the walls were built. Had they not been constructed so deep inside the cave, however, they would probably have weathered away in the 175,000 years since they were erected.

What the structures were for is far from clear. “At this stage, all options are open,” said Soressi. It is not even certain that the walls were made for a specific purpose. But more intriguing to Soressi is what the Neanderthals were doing so deep inside the cave, where the lack of natural light would have left them in total darkness without fires to illuminate the space. The discovery raises plenty of questions, she adds. Were the walls built when Neanderthals found themselves deep inside the cave by chance, or was making underground structures a common practice for them?

“It’s becoming really clear with the Neanderthals, that given their abilities and capacities, there is not so much of a jump between them and contemporaneous modern humans,” Soressi said. “But this is very strange behaviour. I’d like to understand why they did it.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion