Can a Notorious New York City Jail Be Closed?

A former Rikers Island inmate has made it his mission to close the infamous facility.

For Glenn E. Martin, the fight to close New York City’s Rikers Island is personal. Martin spent a year as an inmate there and served five years in a New York State prison after being convicted of armed robbery. He believes his experience, like that of hundreds of thousands of individuals released every year, provides needed perspective in the growing national call for reform. He also believes New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio could do more. The mayor published an opinion piece this month in which he outlined structural and service changes at the facility that have yielded positive results.

Martin is the founder and president of Just Leadership USA, an advocacy organization working to cut the U.S. prison population in half by 2030. He has gathered over 50 member organizations into a national coalition to work on the issue. I spoke to him recently. A slightly edited version of our conversation follows.

Juleyka Lantigua-Williams: Why focus on Rikers, besides the personal connection?

Glenn E. Martin: Rikers is every jail and every jail is Rikers. While Rikers definitely stands out as one of the long standing notorious large institutions that has really turned out a tremendous amount of human carnage over the last few decades, the fact of the matter is that there are many components of Rikers that are reflected in jails across this country where over eleven million people cycle through those jails each year. So, why Rikers? Because it is here in our backyard. As an organization with a very ambitious goal, we can’t imagine doing this work around the country without making a statement about our work right here in our backyard.

Secondly, it happens to be a jail where there has been a tremendous amount of attention recently. What is interesting about this for us is that communities that are affected by Rikers Island have been calling for closure a whole lot longer than some of the elite players that are now weighing in. Why? Because they have experienced the damage that is caused by Rikers Island, it has been long-standing, and there has not been political courage to stand up and do anything about it. The couple of times we have taken a look at whether it is feasible to close Rikers, mainly during Mayor Koch’s administration and then again during Mayor Bloomberg’s administration, the voice of the community has been left out of the discussion even though the community itself has been the one calling for closure a lot longer than anyone else.

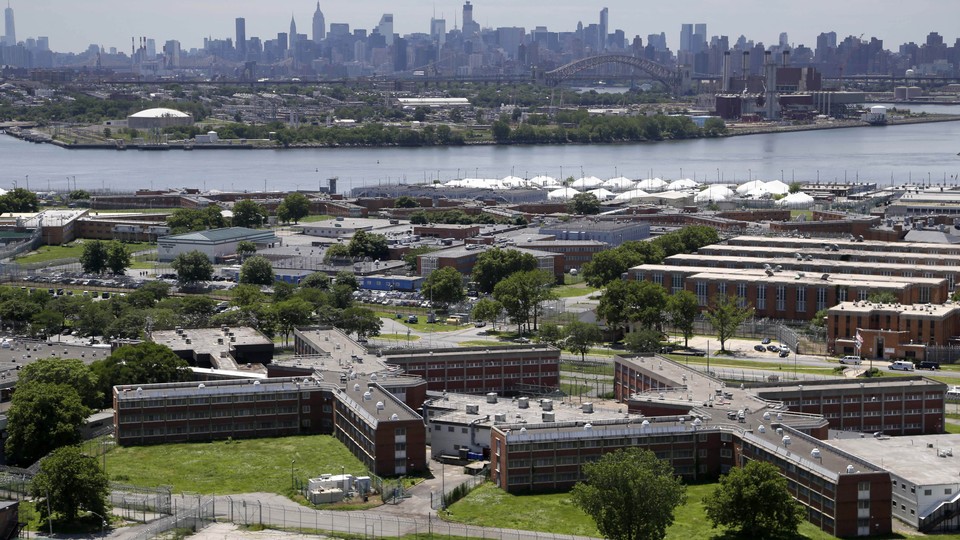

We hope to send a strong message to our allegedly progressive mayor that now is the opportunity for him to do something bold. He talks about “a tale of two cities.” As an organization, we argue that there is a third city that he is not paying attention to and that city is sitting just 200 yards from LaGuardia Airport, Riker's Island, what we call our torture island, here in one of the most progressive resource-rich cities in the United States. It seems like such an abomination for us to have this facility continue to operate. To people who want to be pragmatic: we are spending $167,000 per bed per year to operate a facility that churns out so much damage to New Yorkers, particularly young New Yorkers of color.

Lantigua-Williams: Here’s a pragmatic question: What would the steps be to actually close Rikers?

Martin: Let’s start out by pointing out something most people don’t know, which is when I was on Riker's a little over 20 years ago there were 20,000 people there. We are down to about 7,800 today. So there has already been a tremendous reduction in the number of people at Rikers Island. Even in New York state, our prison population has been down 27 percent in the last 15 years. So there is a precedent for heading in the direction of what we call decarceration and evidence of the fact that we can do it.

I envision a couple of things. One is court delays: In New York City, the average amount of time it would take a person to go to court was 100 days just going back 10 years or so. Now we are up to over 200 days in terms of how long it takes to process a case. So if the mayor used his political capital to engage the Office of Court Administration and the Judiciary and the other players in the court we could reduce court delays. That alone would reduce the Rikers Island population by thousands. Remember, 85 percent of the people at Rikers Island are not convicted of anything. They are just awaiting trial, and most of those folks have bail under $2,000. I think when you put it that way for most New Yorkers, the question is why do we have so many people sitting at Rikers on any given day? The answer is simple: because they are too poor to pay bail and because the bail lobby is pretty strong in New York and across this country. If we were able to work to undo those things, we could reduce the population by half in no time with no jeopardy to public safety in New York.

Lantigua-Williams: Why not push for something “more realistic,” like pretrial services?

Martin: First, the bail industry would be the biggest opponent of going in that direction. Second, the problem with suggesting that pretrial diversion is the way to go is that no one has an appetite for this—even our mayor. Everyone is concerned about the one case that is not going to go well. I hate to tell people, but that is the nature of criminal justice. If we continue to make policy based on that one case that might not go well, we are going to stay stuck right where we are. That is what got us here. What got us here is a bunch of criminal justice policy-making that made for good politics and bad policy, and all of it was based on that one horrendous case. Think of how many laws we have that are named after young white children that unfortunately were killed or hurt or maimed at the hands of someone who should not have been [there] or should of been in [prison]. We have heard the stories over and over—the Willie Horton stories.

Communities that are impacted by these issues would like to see a solution that is commensurate with the scope of the problem. What we are seeing from people like mayor de Blasio and other decisionmakers is they want to create these incremental small boutique programs and then only make eligible people who, arguably, should not have been anywhere near our criminal justice system in the first place. [For example,] right now we are doing electronic monitoring for a few young people that allegedly is going to be a way to keep them off Rikers … From what I hear, there have been no efforts to take it to scale. You also have to think of it this way: if you have a system that is increasingly oppressive to specific New Yorkers in a way that doesn't lend itself to public safety, why does the solution need to be more tethering to the criminal justice system? If we are admitting that these people probably shouldn't be there in the first place, then maybe we should [give] people their liberty until they have their day in court. If their bail is $2,000 $1,500 that to me is indicative of a judge suggesting that this person doesn't represent any significant risk to public safety. What is really holding these people in jail is that if you are on public assistance $2,500 may as well be $2 million. These people end up stuck on Rikers.

Lantigua-Williams: Let’s talk about the rest of the country. What’s your proposal for cutting the jail population by half by 2030?

Martin: Let’s remember that 636,000 people are released each year, even though we have 2.2 million in prison on any given day, which means that you need to go further upstream and figure out where the bodies are coming from. It means that your policies way upstream are a huge part of the problem. We believe what has been missing from the discussion is an ingredient that is included in every civil rights movement within the United States, every movement, which is leadership from people it impacts, the voices of people who have been most impacted by the system being elevated and being allowed to speak out about how the system has affected them. 70 million Americans have a criminal record on file, but where are those voices? Where are those leaders?

When you have an issue that affects 70 million Americans if you are not investing in their voices, you are not creating a space for them to come out of the closet. If you are not giving them a chance to lead, then your movement is doomed from the beginning. I think that formerly incarcerated people are served up in a way that serves the needs of what has become a very professionalized and institutionalized movement to reform the system that doesn't match the type of damage that has been caused in the community that I care most about.

Lantigua-Williams: Do you see a role for police and correction officers in this?

Martin: My older brother was a correctional officer for 10 years and now he is a US Marshall and my father was a police officer. I approach this issue from multiple lenses, multiple perspectives, and I try to leave space for all stakeholders to have a voice in moving towards a more progressive criminal justice system. I do believe, however, that law enforcement agencies are mostly paramilitary in their structure, which means that cultures are heavily ingrained and even when you have progressive leadership it is still difficult to shift those cultures.

In fact, part of my motivation for closing Rikers was hearing commissioner Martin Horn on his retirement day after 40 years in correction say that his biggest disappointment of his entire career was his inability to shift the culture at Rikers Island one bit. That was really powerful for me to hear, and so I am hopeful that folks in law enforcement can see themselves as change agents to move towards a more progressive criminal justice system, particularly because many of those folks are now people of color who you would assume would be natural allies.

However, I also understand that systems change people long before people change systems. When you’re this bright-eyed bushy-tailed rookie officer or rookie correction officer going into a job wanting to change the world, I think it is really difficult. I think they find that not only is there inmate-on-inmate violence and officer-on-inmate violence but officer-on-officer violence if you don't become part of the culture and you don't assimilate. I think to it is a really difficult place to fight from. I had a correction counselor who took the time to tell me I should go to college and that was a moment in my life that turned things around, so I do think there are things that people in law enforcement can do in terms of individual relationships to really try to help people in one-on-one relationships. But it is going to be a rare case where any one officer, or handful of officers, are able to shift an entire culture, particularly because of the paramilitary nature.

If I had my way, and we were starting from scratch, no correction officer job would be a career job. At the very most people would work seven years in correction and that is it. It would not become a career job tied to a union and a pension. When you monetize misery, when you decide that some groups of people are going to benefit based on the disadvantage of another group or based on the punishment of another group you end up with what we have ended up with, which is not just the privatization of punishment in this country through private prisons and private probation but also government-run institutions that have a perverse incentive to continue to operate. What I am saying is that the system has a life of its own. We have created this monster that needs to continue to feed and it feeds on the fact that we have decided to criminalize so many new things to keep the system going.