ln Washington state, a fledgling movement is looking at bringing back parole to reduce the number of people behind bars. Liberals and conservatives nationwide are questioning “tough-on-crime” policies that have contributed to the world’s highest incarceration rate.

Watching Anthony Wright deliver a speech, you’d never guess that about a dozen years ago he was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to 138 years in prison.

Even in his prison-issued gray sweatshirt, he exudes the confidence of a practiced speaker. “Good afternoon!” he began at the Monroe Correctional Complex last year for an annual conference held by inmates like Wright, members of the Concerned Lifers Organization.

“Good afternoon!” the crowd responded.

He smiled and held his hand over his heart. “I feel the love.”

Then he got to the point. “Is human transformation possible?”

“I know men who challenge their insecurities day in and day out. Weeks on end. Months on end. For years. I see true transformation. But guess what? The public doesn’t.“

A fledging local movement is trying to get the public to look inside this locked-away world, and to accept the idea that some people no longer need to be there. Activists, lawyers, judges and at least one prosecutor, King County’s Dan Satterberg, have during the last six months been discussing the possibility of bringing back parole or some system to review what Kirkland Democratic legislator Roger Goodman calls “unbearably, incomprehensibly long prison sentences.”

In meeting rooms and prisons, sometimes including the ideas of inmates themselves, the conversations have attempted to settle on proposals for the 2016 legislative session or the one after. The state Sentencing Guildelines Commission is to hear two proposals at its Nov. 20 meeting.

It’s well understood as a tough sell, despite the likely need for a costly new prison if the number of incarcerated isn’t reduced.

“I just want to wake you up to the political reality,” said Goodman, chairman of the state House Public Safety Committee, at a June kickoff held by the Washington Coalition for Parole.

Around the country, liberals and conservatives are asking whether throwing away the key for massive numbers of inmates makes sense. The effort has financial and moral implications, and raises fundamental questions about the nature of justice.

Decades of tough-on-crime policies have left the United States with the world’s highest imprisonment rate — one that has amounted to “huge costs in dollars and lost human potential,” as former U.S. House Speaker Newt Gingrich and former Republican California legislator Pat Nolan wrote in a 2011 Washington Post op-ed.

Momentum against mass incarceration has continued to pick up steam. The Koch brothers, billionaire industrialists known for pouring money into conservative causes, are teaming with the Center for American Progress, a liberal think tank, and the American Civil Liberties Union to find ways to reduce the prison population, rethink sentencing and reduce recidivism. In July, President Obama became the first sitting president to visit a federal prison, where he marveled that locking up so many people is “not normal.”

The federal government is now in the process of granting early release to roughly 6,000 drug prisoners. And in Virginia, the governor announced a commission to study the possibility of reinstating parole.

Washington, where the prison population stands at about 18,400, is somewhat unusual. Along with Virginia, it’s among the roughly one-third of states without parole, according to Marc Mauer, executive director of the reform-oriented Sentencing Project.

Prison population,

by the numbers

Approximate state prison population: 18,400

Inmates 65 and older: 519

Inmates serving at least 15 years: 6,164

Approximate number serving life without parole: 663

Source: Department of Corrections

States that don’t have parole usually got rid of it in the 1980s and ’90s to conform with a growing call for “truth in sentencing.” Life means life, as the saying went, not 15 years before getting out on parole.

That wasn’t Washington’s only motivation. The Sentencing Reform Act, which also standardized sentences, aimed to eliminate inconsistencies and racial bias that came with judges’ and parole boards’ discretion.

But those championing new reforms say the current system — which still allows parole for some inmates, including those sentenced before 1984, hurts everyone, especially African Americans, who make up a disproportionate share of the prison population.

Such reform “is exactly where the conversation needs to go in Washington,” said Alison Holcomb, a Seattle lawyer leading the ACLU’s national, multimillion-dollar project to combat mass incarceration.

Yet, she said, the conversation may be hampered by Washington’s self-image. “We don’t see ourselves as one of the ‘bad states,’ ” she observed. “People think the problem is in Texas, or Florida or Louisiana.”

Just ask Mike Padden, the Spokane Valley Republican who chairs the state Senate’s Law & Justice Committee, giving him an outsized role in determining whether legislation will live or die. “We’ve already done so much,” he said, noting that Washington has one of the nation’s lowest incarceration rates.

Indeed, drug courts and other sentencing alternatives flourish in Washington.

At the same time, the incarceration rate has jumped — more than doubling since 1980 — just not as fast as most everyone else’s. In the same period, the operating costs for the state prison system have quadrupled, to $857 million last year, according to the Washington State Institute for Public Policy.

The three-strikes law, passed in 1993 as the nation’s first and still one of its toughest, plays a part, eliminating the possibility of parole for those convicted three times of serious crimes. The Hard Time for Armed Crime initiative, passed by lawmakers two years later, dramatically lengthened sentences for crimes with guns.

According to the Department of Corrections, roughly a third of Washington’s inmates are serving sentences of more than 15 years; 663 are serving life without parole, 289 of those under the three-strikes law.

“I think locking people up forever and ever without taking a second look at them is indefensible,” said Carol Estes of the Washington Coalition for Parole. As a longtime volunteer at the Monroe prison, she’s convinced that people change.

Snohomish County Prosecutor Mark Roe believes that, too. “I am completely blown away at times at how different these guys are from when I prosecuted them,” he said.

“But some of them did absolutely evil things. And I believe in punishment.”

A child’s murder

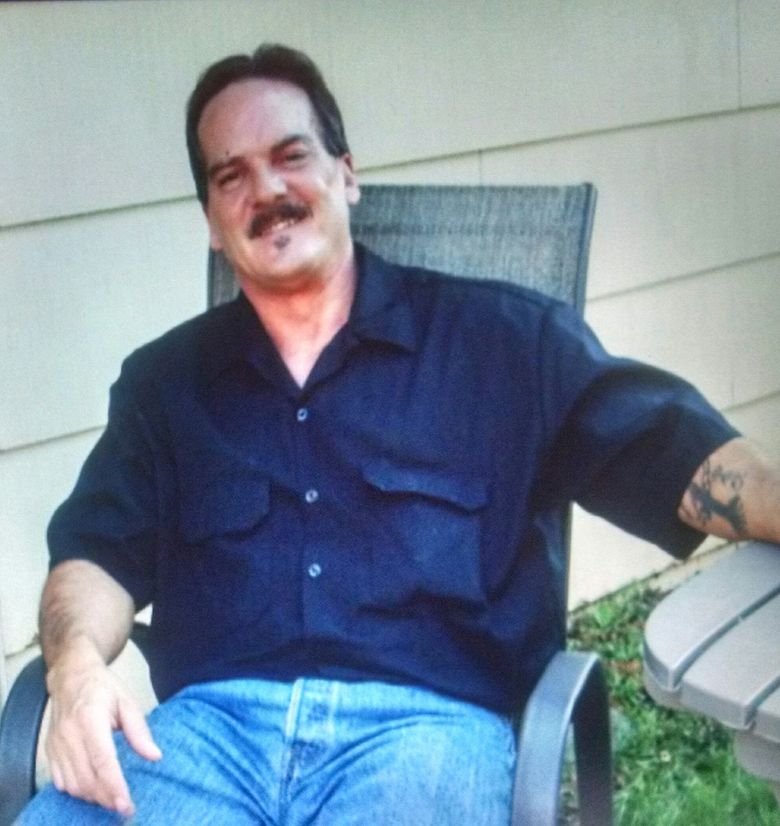

On the night of Feb. 9, 2001, Anthony Wright, then a gang-affiliated crack dealer in Spokane, walked up to a house where he believed a man owed him money. Two men came along, according to court records.

In short order, bullets ricocheted through the house. One hit 3-year-old Pasheen Bridges. She died within the hour.

Wright maintains he didn’t fire a shot. A jury convicted him not only of murder, but attempted murder and six counts of first-degree assault, owing to all the people in the house at the time.

Although just 28, he couldn’t possibly see the end of his 138-year sentence.

He’s 42 now. One thing about prison, he says, you have time to think. Over and over again, he said he asked himself: “Where did I go wrong?” He came to some conclusions, including the fallacy of his drive to make money “by any means necessary.”

Most Read Local Stories

To a large extent, what saved him was math. Taking courses through the nonprofit University Beyond Bars, co-founded by Estes, he loved that “you got one answer but you can get there all kinds of ways.”

He started tutoring other inmates. At the lifers conference last year, he brought down the house with a story of how he motivated a three-striker who was trying to get a GED but struggled with math.

“If you were in a boxing match and someone hit you in the chin really hard — boop — knocked you down. Would you look up at him and say, ‘I quit?’ Let’s just say he gave me a real strong no, an emphatic one.

“I said: ‘Well, math is kicking your ass, what you going to do?’ ” The inmate persevered.

How do you measure Wright’s seeming transformation against the life of the toddler he helped kill?

He knows that lies at the heart of whether he should get a chance at parole. It’s a hard question, he said, really hard. And his ultimate answer is this: “I think I can do more good out there.”

Lew Cox, executive director of Violent Crime Victim Services, a Tacoma-based nonprofit, is skeptical of such claims. He said he’s working now with a man whose daughter was murdered by a Florida parolee.

Cox’s own daughter was murdered in 1987 and, as it happened, he spoke this past week, hours after attending the California parole hearing of her killer. Such hearings, he said, “revictimize the families,” who relive their pain. He spoke with bitterness about the board’s decision to release a “psychopathic” murderer.

Even some considering a system of early release have their limits.

In meetings over the summer and fall, a Sentencing Guidelines Commission subcommittee weighed a proposal that would allow all inmates to be considered for early release after 15 years.

“I don’t think 15 years is long enough,” said Satterberg, the King County prosecutor, who is on the subcommittee. Not when it comes to aggravated murderers.

Instead, according to Satterberg, the group will recommend that the larger commission focus on two groups: offenders older than 60 and three-strikers — in both cases, only those who serve at least 20 years.

Of the older inmates, Satterberg said, “they no longer pose a risk for public safety, at least as an actuarial matter.” Studies show recidivism declines markedly with age, while prison costs escalate due to medical care.

As for those serving under three strikes, Satterberg has long argued some do not deserve a life sentence, especially those who might have been sentenced to a year or two in prison before the law was passed.

Statistics are hard to come by; the state keeps spotty records on three-strikes cases. But newly compiled figures from the Washington State Caseload Forecast Council show that 58 people have “struck out” on a robbery 2 or attempted robbery 2 charge, crimes that don’t involve physically hurting anybody.

‘I screwed up’

“Is it true he never touched anybody?”

In 1997, then-King County Superior Court Judge Michael Fox asked that question of a prosecutor handling a three-strikes case against Joseph Scott Wharton, an addict who over a decade had held up a string of stores and banks by pretending he had a gun in his pocket. As Fox recounts the story, the prosecutor affirmed his understanding. But, given the law, the judge had no choice but to hand down a life sentence.

It haunted him. Justice, he felt, had not been served. Thirteen years later, approaching retirement, he finally set out to do something about it. He visited Wharton in prison, satisfied himself that the three-striker had behaved well and lined up a pro-bono attorney for him.

Although Washington lacks parole, offenders do have one shot at review: a clemency hearing — if they can get one. The state Clemency & Pardon Board holds only a few dozen a year, then its recommendations often sit with the governor for months or even years, awaiting a decision.

Wharton got a hearing. Impressed by Fox’s testimony, the board recommended release. In 2013, Gov. Jay Inslee concurred, on the condition Wharton spend nine months at an addiction-treatment center.

But Wharton faltered at the center. He found its behavioral techniques demeaning and he butted heads with his counselor, all the while dealing with a bout of bronchitis and a dying mother.

After a couple months, he walked out. He returned two days later but quickly left again, hoping, he said, to find a different treatment center. Three days after that, he turned himself in to the Department of Corrections — but not before trading a pack of cigarettes for two lines of methamphetamine with a guy he met at a bus station.

Early release comes with risk; relapse is always possible. Yet, not all relapses are equal.

If Wharton had been out on parole, Fox speculated, his slip-up might have been handled the way drug court handles those who show up with a dirty urinalysis. “We’d put them in jail for a couple weeks.” But there are no provisions for slip-ups with clemency, which depends entirely on the governor’s favor.

Inslee revoked Wharton’s clemency.

“He violated the rules, and he did so in a way that could have potentially caused problems for others,” said Nicholas Brown, Inslee’s general counsel.

“I screwed up,” Wharton conceded, speaking by phone from the Washington State Penitentiary in Walla Walla. “But I don’t think it warrants sending me back to prison for the rest of my natural life.”

His only hope now, aside from the possible enactment of parole, is that the governor might change his mind.

‘What’s the point?’

On Sept. 19, the Concerned Lifers Organization held its annual conference. This time, inmate Devon Adams brought 10 or so fellow offenders on stage as part of his presentation on “the graying of prisons.” They were elderly men, who more than looked their age. One could hardly walk and carried a supply of oxygen.

Two days later, in a windowless meeting room inside the Monroe Correctional Complex, a couple dozen members gathered. “I couldn’t be more happy,” said Nick Hacheney, one of the group’s leaders. “My hope is that we can continue to build momentum.”

As they discussed where to put their focus — those over 50, over 65, everyone? — the conversation turned repeatedly to what it was like to grow old in prison. One inmate, Michael Cornethan, who had spent a fair amount of time in a fourth-floor medical unit, began to cry. “When I’m up there, it’s like I’m never coming back.”

Roe, the Snohomish County prosecutor, didn’t witness that. But he did attend the September conference and see the parade of elderly. “That almost made me cry,” he said.

“I don’t know if I would have felt differently if I was holding pictures from the crime scene,” he added. And he still rails against what he calls “a movement to just let everyone out.”

But at that moment, looking at those men, he asked himself: “What’s the point in keeping them locked up any more?”