If you return a game after completion that’s theft, but what if the content of the game itself was stolen? Welcome to the minefield that is The Beginner’s Guide.

Recently we examined the perception that realistic pricing is virtually untenable for indie developers, because the public seems to carry the misconception that indie = amateur. The release of The Witness – the game that inspired the debate – seems to have vindicated the argument that indie games can price closer to AAA than bargain bin, with Jonathan Blow’s puzzling opus selling well over 100,000 copies in its first week, to the tune of $5m in gross receipts.

Out of that glowing numerical success, however, comes a more ignominious statistic: The Witness is currently one of the most pirated games on popular torrent sites. All of a sudden, we’re having to address the issue of piracy among indie games, something that at one point seemed inconceivable, and it brings to mind another moral debate around indie games from before the holidays.

At the tail-end of last year, Destructoid writer Laura Kate Dale caused a furore with her 2015 round-up when she suggested that people may want to apply for a refund after completing The Beginner’s Guide, making use of Valve’s no-quibble Steam refunds policy. The bowels of the internet, always within a whisper of forming a lynch mob at a moment’s notice, quickly swept her up in a maelstrom of hatred and fury.

“She’s advocating piracy!” They howled, plaintively, pitchforks raised and torches ablaze.

The general feeling of the amorphous internet beast was that Dale was condoning theft of The Beginner’s Guide by suggesting to the millions of monthly Destructoid readers that they return their copy of the game, even after they had completed it. This was possible because the Steam refund policy has some pretty definitive criteria:

You can request a refund for nearly any purchase on Steam—for any reason. Maybe your PC doesn’t meet the hardware requirements; maybe you bought a game by mistake; maybe you played the title for an hour and just didn’t like it.

It doesn’t matter. Valve will, upon request via help.steampowered.com, issue a refund for any reason, if the request is made within fourteen days of purchase, and the title has been played for less than two hours.

And there you have it, the nub of the issue: “If the request is made within fourteen days of purchase, and the title has been played for less than two hours.”

This clause is designed to stop people from buying games on Steam, completing them, and then punting them back to Valve for a full Steam refund. It’s the Blockbuster VHS problems for the digital age. In the most part the system works because generally take longer than two hours to complete, and you will probably play a title for less than two hours (if at all) to find out that it doesn’t run on your PC, or whatever other legitimate reason you have to request a refund via Steam refunds.

The trouble is, The Beginner’s Guide only takes an hour and a half to complete, and this is where we enter a grey area in the no-quibble nature of the Steam refunds policy.

It’s also worth mentioning at this point that there will be some hefty spoilers for The Beginner’s Guide coming here, so now is your time to look away. I strongly suggest you avoid all spoilers if you intend to play the game, as it functions best as a complete surprise. If you want a relatively spoiler-free examination of the game, read the non-review I wrote of it upon its release.

First of all, let’s get something out of the way: Laura Kate Dale was not advocating the theft of The Beginner’s Guide in her article. That would be immoral and grossly irresponsible, and approaches a depth of anarchy that even the mighty Destructoid wouldn’t plumb. Unfortunately the internet troll hive-mind chose to interpret her words in that way.

What she in fact meant, and clarified this in a later edit, was that if you got to the end of The Beginner’s Guide and were not entirely happy with it – for reasons we’re about to expand upon – then you should return it, and would be entirely within your rights to do so.

Why? Because depending on your interpretation of the premise and narrative arc of The Beginner’s Guide, the game could be interpreted as stolen wholesale from another developer by its creator, Davey Wreden (of The Stanley Parable fame).

The Beginner’s Guide

The Beginner’s Guide tells the story of Wreden’s relationship with another indie developer, known throughout the game simply as Coda. Ostensibly it’s a story about a friendship, set against the background of video game development, and begins with us walking through Coda’s earliest known creation: a map for Counter-Strike.

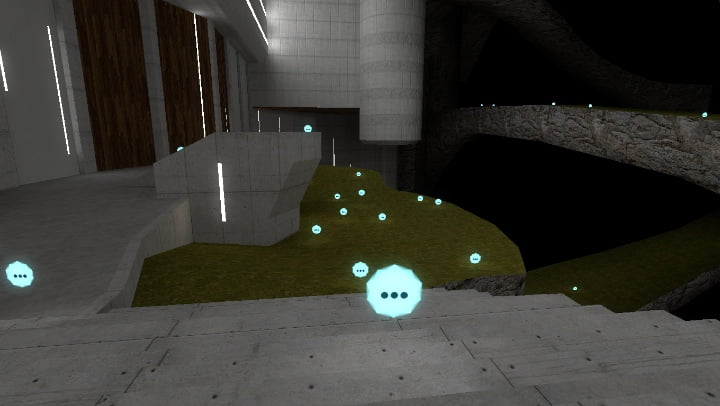

Wreden, who narrates the entire story from start to finish as we walk free-form through Coda’s Counter-Strike level – and latterly, through his world as viewed through the lens of his original developmental creations – explains some of the odd details of this Counter-Strike map. It has familiar elements of course, but some odd tweaks that look out of place in amongst the sand and crates.

As The Beginner’s Guide progresses we move through different game snippets, all the work of Coda, with Davey Wreden’s narrative whisking us through his friend’s increasingly creative and complex world like an indie development guided meditation. We start to be introduced to some of the quirks of Coda’s development and become aware that perhaps their idea of a ‘video game’ is different to how we – or indeed our narrator – might see it.

In one sequence, as you approach a door your movement speed drops exponentially the closer you get to your goal, and it feels like you’re never going to reach it. And all gamers instinctively know that all doors must be walked through, just as all boxes must be opened. It’s in our programming, never mind the programming of the games. In the end Wreden writes in a change to the game “on the fly” that allows you to hit Enter and jump past this quicksand mechanic, and it’s a technique we see repeated throughout The Beginner’s Guide. Soon after you’re locked inside a prison cell and without Wreden’s omnipotent intervention, would have to wait a full hour for the cell to open before you can proceed.

The simple beauty of Wreden’s “let me change that for you” interventions are that you have to hit a button to accept them. If you’re feeling righteously masochistic you could choose to work through (or not, as the case may be) these sections of Coda’s game snippets in the way they were intended, without the hand of Wreden.

When you stare into the abyss

It’s at this point that we begin to get a sense that not all is right in Coda’s world, and Wreden is eager to point this out through his narration. He speaks of the differences between his approach and that of his friend, an individual who likes building cages without exits and games with no ending, and begins to sound concerned for his friend’s mental state as we retrospectively pick through Coda’s back catalogue.

Two things are quickly becoming apparent:

- Coda doesn’t feel a video game needs to be beaten, or indeed beatable. Coda is happy for games to be obtuse or cyclical, or even downright impossible. Wreden, on the other hand, thinks games should have a central aim or purpose that the player is striving towards, and that anything else is at best absurd; at its worst, it may be a sign that Coda is losing their grip.

- Wreden believes that games are to be shared, and that there’s no point pouring the time and effort into development if nobody is going to see it. Coda, on the other hand, is an introspective sort who appears to be developing purely for their own interest. The very fact Coda is sharing their games with Wreden at all is remarkable, and the fact Davey keeps attempting to share Coda’s creations with others – to prove to Coda how good they are with external validation – upsets the balance of their friendship.

Wreden is telling us the story of their friendship chronologically through Coda’s work, entirely in the past-tense; a story to which he already knows the conclusion, and he sounds more troubled and melancholic as the game progresses. The darkness, the prevalence of prisons and unsolvable scenarios, the faceless angst of Coda’s creations are becoming increasingly upsetting, both to Wreden and to us, the voyeuristic player. There is one constant that keeps giving our narrator hope, however: the prevalence of lampposts seeming to signify the end of Coda’s experiments in game design, and a path back from this innate darkness.

The abyss stares back

Then everything changes. As a result of Davey’s persistent meddling, as Coda sees it, and his attempts to showcase his friend’s work against their wishes, things come to a head. Abruptly, Wreden and Coda are no longer friends, and for all intents and purposes, Coda disappears.

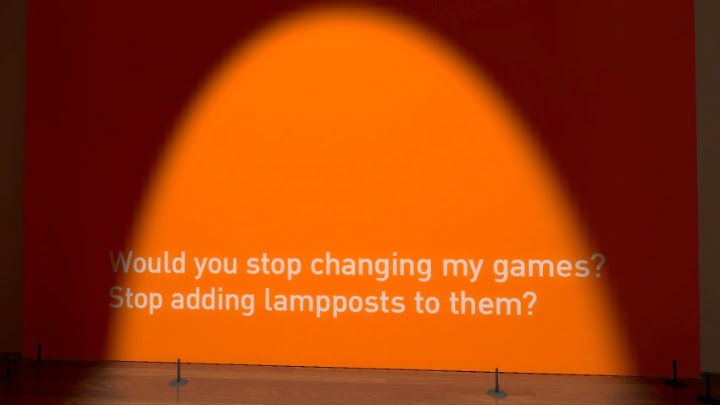

Wreden is left with a single game, seemingly darker and more obtuse than everything that has gone before it, as a parting salvo. In order to progress through this most final and fiendish of works, Davey is again forced to tinker with the game in order to make any progress. He re-jigs puzzles and pulls combinations for locks out of the game’s code, and we progress down the rabbit hole into this swirling vortex of madness.

As we work through twisting corridors towards a conclusion, words are appearing on the walls around us. They’re a message, seemingly senseless at first, but the more the game reveals the more sense it makes. It’s a final message from Coda to Wreden, chastising the former friend for his repeated intrusions and broken trusts. One phrase stands out, head and shoulders above the others:

“Would you stop changing my games? Adding lampposts to them?”

Our narrator, filled with guilt and anguish, talks us through how wrong he’s been; that there’s nothing wrong with Coda or these games. Coda is just a developer who likes making prisons and doesn’t believe all problems require a solution. It’s Wreden who has been wrong this whole time.

Then Wreden reveals his ultimate betrayal: the reason he has put The Beginner’s Guide together is as a message to Coda, who has been impossible to communicate with since the rift opened between them. He knows full well that to publish a raft of Coda’s games is the worst crime he could possibly commit against his introverted friend, but what other option does he have? He’s desperate, and this is his Hail Mary pass to try and get his former friend’s attention.

It’s simultaneously a heart-rending and genuine apology, and the most heinous of all dick moves. Yet it’s made somehow far worse by the fact that we feel entirely complicit in it, because we didn’t know what we were doing at Wreden’s behest until he dropped the curtain during those painful final moments.

Reasonable doubt

And now, we get back around to the issue of Laura Kate Dale’s Destructoid piece and the issue of the Steam return advice.

She herself paid for the game because she feels it is a work of narrative fiction, but firmly believes that you are entitled to a refund on The Beginner’s Guide if you believe Davey Wreden used someone called Coda’s work to earn money through a saleable game without express permission. He even admits it’s in flagrant disregard of Coda’s wishes several times throughout his narrative.

It’s a cogent and rational argument, and if that is your interpretation of The Beginner’s Guide then you are entirely entitled to get your money back via Steam refunds. The fact that it doesn’t become apparent that the work has been used without permission until the very end of the one-and-a-half hour experience is no fault of the player, and they are rendered unable to make that moral objection earlier on. Normally Steam refunds would be designed to protect a developer or publisher from the return of completed games, but you can literally only return The Beginner’s Guide for this specific reason if you have played to the end and fully understood it.

But there’s another way, the one I prefer to cling to, and that’s the notion of epistemic uncertainty. With that in mind, answer me one question: do we know for certain that the story told in The Beginner’s Guide is true, and to what degree?

The greatest trick the Devil ever pulled

Think back to the first time you played The Stanley Parable. That game, almost unanimously hailed as a work of genius, was a remarkable beast. To play through it once is a joyous romp through our perceptions and preconceptions; to play through it several times and deliberately try to circumvent the will of the narrative can reveal some spectacularly strange results, that will have you beaming from ear to ear.

And all of that? The rail-roading, the second-guessing, the feints and the bluffs and the misdirection and the whimsy and the mischief and… that came from the mind of Mr Davey Wreden. The Stanley Parable is in reality a far stranger beast than The Beginner’s Guide, and the notion that everything that occurs within The Beginner’s Guide could be a construct of Wreden? It’s not a difficult leap to make, when you stop and take a moment to think about what he’s really capable of.

The beauty of The Beginner’s Guide is not knowing. You cannot possibly know for certain, one way or another, whether the work of Coda and the story of Wreden’s betrayal is 100% truthful and accurate, or a complete work of fiction; or, somewhere in between those two stations… and in all honesty, I don’t want to know the truth.

It could be a heartfelt and self-deprecating apology or it could frankly be total bullshit – and then, it could be somewhere in between – but it’s either a devastatingly sad truth or fantastically wonderful bullshit, or a magical mixture of both. The epistemic uncertainty of The Beginner’s Guide is a key part of what makes it such a joyous anomaly, and let’s face it: there needs to be a little more wonder and mystery in this world.

In The Beginner’s Guide Davey Wreden might have totally Keyser Söze-d us, and if you have any doubt at all in your mind then it’s hard to legitimately justify returning the game. There’s a temptation to reach out to the man himself and ask, but the absolute truth of the matter is that I hope we never know for sure.