Six years ago, just before her 47th wedding anniversary, Carol Hudson’s husband, Tony died unexpectedly. Left behind, occupying half their home, was a lifetime of stuff, “the leftover scraps of ordinary life,” she says.

Working out what to do with it – not valuables, heirlooms or personal bequests, but everyday life-worn objects and clothing – was, she says, a vital part of coming to terms with his death. “There seemed to be clear rituals associated with a body, but not with possessions. What was I supposed to do with them? What did they mean to me? Rationally, I knew he wasn’t coming back but, emotionally, keeping his things suggested he might.”

A photographer for more than 30 years, Carol’s instinctive reaction was to take up her camera. Systematically, she set about photographing the belongings, from piles of jumpers and drawers full of socks to a patched up bike chain, scratched spectacles and a body-moulded leather bag.

It began as a project with no clear purpose – “I always photograph, that is how I get through things” – but the resulting collection of images has now become the subject of a website, The Power of Possessions. Carol hopes it will encourage others to think about the emotional value of what we and our loved ones leave behind.

With the owner gone, possessions are effectively dispossessed. “They seem to float in space, as if they were all attracted by the person, the magnet in the middle that is gone,” says Carol. Yet by making images, then putting a series of them together, she realised she could create a vivid portrait of her husband. “Belongings, the signs of their use, say something about a person. Put together, a series of images can tell the narrative of a life.”

Using the lens to filter and focus, Carol found herself able to organise Tony’s story in her own mind. Details she had never noticed in his lifetime were thrown into relief by the camera.

“I had overlooked many of Tony’s possessions before. I didn’t see them. Sometimes they even got in my way,” she says. “I was forced to turn my attention from him to his things. I looked at them differently.”

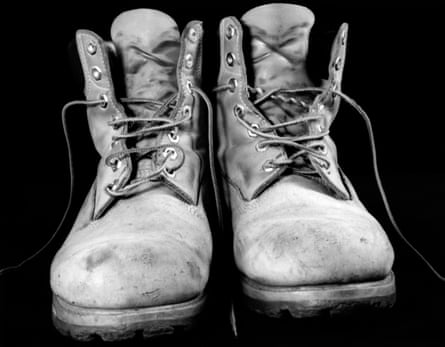

What she sought was the sign of his touch in the wear and tear. Newer items with higher monetary value revealed little. “In the things that were used, I found a bit of him. There was some power lingering there. It was almost an embalming.”

Examining a photograph of an old pair of boots, Carol saw, for the first time, grooves in the leather. “He had very weak ankles from a childhood incident and they often twisted. He always tied his laces extra tight for protection. I had never noticed those indentations before because I had never really looked at his boots.”

In a pile of jumpers, she recognised another of her husband’s idiosyncrasies. “The cuffs were all turned up. He always found the sleeves too long.”

Everything was neatly sorted and stored. Handkerchiefs were folded and separated by colour, socks and belts carefully rolled. Books were marked with the date he had finished reading them. “He was tidy and organised, meticulous,” says Carol. “He had a lot of things. He didn’t dispose of them, he repaired them – a bodge job, usually – he wasn’t bothered about new and fancy possessions.”

Although she carries a small camera for spur-of the-moment snaps, this time Carol chose a large-format camera. “I wanted detail so that the pictures had descriptive qualities,” she says. The result, she believes, gives a powerful texture to the images. “Some are so close up you can see the cat’s hairs. They feel somehow very intimate. I wanted them to have that sense of touch, even smell. Somehow I have translated the touch into something visual. It helps me remember him better.”

Tony was a film cameraman and Carol used his equipment to light the pictures. Her tripod was a gift from him and she developed the images in the small darkroom at their home. “I felt he would have understood what I was doing. It fitted with who we were. I enjoyed those links to him.”

The process – “slow and ponderous” – was deeply absorbing. “When I started there was a kind of relief. It felt ritualistic.” The light on the film, creating the prints, struck her as a powerful and comforting analogy for the trace of her husband’s touch.

The pictures were not always easy to take. Alongside the many possessions Carol knew well, she found several about which she knew nothing.

In the loft, she discovered a case of letters between Tony and his first wife. “They were in two piles – to him and from him,” says Carol. “I knew about the marriage, of course. It was very brief and over before we met, but these letters were never for my eyes. I had no right to read them.”

Instead, Carol photographed the two piles. “I was interested in what was inside but I realised I was more interested in thinking about not knowing. I looked at the stationery, the way they had been opened. I didn’t need to read them. I captured the possibility and my choice.”

More unsettling still was a stash of photographic contact sheets. “I couldn’t really choose not to see, but I didn’t feel I or anyone else should have access to them.” She decided to shred the images and photograph the result, a 5ft high paper pyramid. “I wanted it to look quite monumental,” she says. “I believe there is a right to be forgotten as well as to be remembered. Tony’s death was sudden so he had no time to edit, to put his house in order.”

In future, with digital technology, she wonders, will that right to privacy be even harder to protect.

The couple had no children and as a result, says Carol, the responsibility of deciding what to do with her husband’s things could not be shared. “Was it my right to dispose of them? There was no other claim on them and yet they had not been specifically bequeathed to me. They were just left. Although we were married such a long time, they were not mine. I still had a sense of intrusion.”

When photography colleagues, with whom Carol had discussed the project, suggested she share the work, this discomfort was heightened. Should she use the pictures as something more than a “personal coping strategy”? Some friends found the images – despite the mundanity of the subject matter – difficult. “I suppose it would be like wearing someone’s clothes. He had not actually invited them to. The clothing in particular seemed to them intimate.”

A photography lecturer, Carol nevertheless decided to turn the work into a research project and subsequently – after an exhibition was well received – into a website. It was, she feels, something of which her husband would have approved.

Interestingly, despite their professions, the couple took few photographs of each other. They married at Gretna Green, with two witnesses they met in the car park. There were no pictures. “I hadn’t realised we had so few until he was gone. I couldn’t find a single one of us together. I regret it now,” she says.

Professionally, Carol has always preferred photographing people to objects (“something Tony never quite understood”). Perhaps, then, these images speak to her more directly than a portrait would have done?

“When Tony died I started looking for a picture of him to put on the wall. I couldn’t find anything I felt really captured him,” she says.

Only recently has she felt ready to begin disposing of her husband’s things. “My clothes have slowly expanded to fill the wardrobe. His went into boxes. It goes bit by bit. Having the pictures has made that process easier. I look at them and there is his touch frozen in time.”

carolmhudson.com

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion