What Happens If Aleppo Falls?

Why the Syrian war—and the future of Europe—may hinge on one city

This week, the Syrian army, backed by Russian air strikes and Iranian-supported militias including Hezbollah, launched a major offensive to encircle rebel strongholds in the northern city of Aleppo, choking off one of the last two secure routes connecting the city to Turkey and closing in on the second. This would cut supplies not only to a core of the rebellion against Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, but also to the city’s 300,000 remaining civilians, who may soon find themselves besieged like hundreds of thousands of others in the country. In response, 50,000 civilians have fled Aleppo for the Turkish border, where the border crossing is currently closed. An unnamed U.S. defense official told The Daily Beast’s Nancy Youssef that “the war is essentially over” if Assad manages to seize and hold Aleppo.

The city, formerly Syria’s largest and its commercial and industrial hub, has proven pivotal to the civil war in the past. As Andrew Tabler of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy explained to me, the rebels’ push to take Aleppo in 2012—following a year in which the city had seen relatively little of the protests and violence that had been escalating elsewhere in the country—“was one of the first real major offensives of the armed opposition in Syria.” The hope was to set up an alternative capital there to rival Damascus, and from that base to gradually expand opposition control. The city has been roughly divided between the regime and the rebels ever since, with Assad’s forces mainly in the west and opposition forces mainly in the east, and “with some parts of the city changing hands on a daily basis,” according to the BBC.

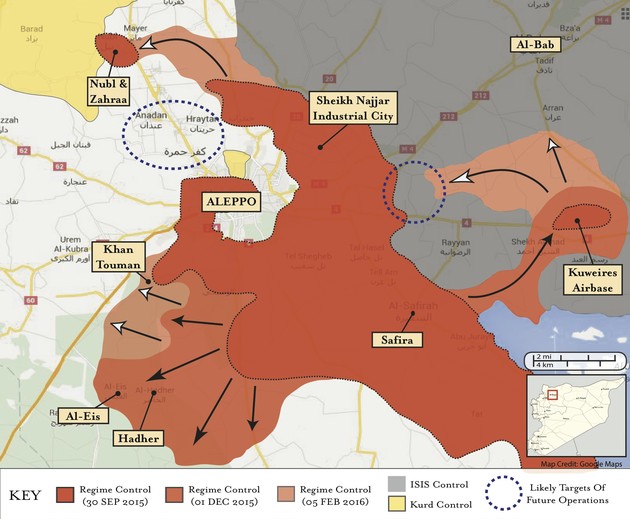

Critically, the rebels have controlled major roads to Turkey, which has allowed them to transport supplies into their half of the city and to their other strongholds in northern Syria. Government forces in western Aleppo, meanwhile, have been cut off from those ground routes and forced to rely on airplanes and helicopters to get supplies. As Aleppo became the site of a bloody urban war of attrition—in late 2013, Assad’s forces barrel-bombed the city for a month straight, and they have repeatedly tried to encircle it—the rebels have held on.

Russia’s military intervention in Syria, which began last fall, may change that. Unlike the U.S. coalition’s air strikes in the country, which have targeted ISIS-controlled areas in eastern Syria, Russia’s are targeting rebel groups, some of them backed by the United States, in the country’s west, including near Aleppo. “[T]he bombing over the last four months has significantly softened up the opposition, and decimated them in many areas,” Tabler said. Against that backdrop, and barring an unlikely breakthrough at international peace talks scheduled to resume this week (after they were called off following the Syrian army’s advance on Aleppo), the regime offensive to recapture the city may ultimately succeed, even if it takes starving its inhabitants into submission.

I asked Tabler to walk me through what Aleppo has meant to the rebellion so far—and what would happen if the city falls to Assad. An edited and condensed transcript of our conversation follows.

September 30, 2015 to February 5, 2016

Kathy Gilsinan: I wanted to start with what the significance of Aleppo has been to the Syrian uprising up to this point.

Andrew Tabler: Aleppo is Syria’s largest city. It’s the commercial hub. It is extremely important, particularly to the opposition, because Aleppo, along with the other northwestern cities, have been some of the strongest opponents to the Assad regime historically. I think the decision in 2012 to take [the city] was one of the first real major offensives of the armed opposition in Syria. And they hoped that by denying the regime Aleppo, it would set up an alternative capital and allow for a process where the Assad regime’s power was whittled away. Since that time, it has instead been one of the most bombed, barrel-bombed, and decimated parts of Syria, and now is much more like Dresden than anything else.

Gilsinan: What’s changed that the regime looks like it’s about to retake it? Why not in 2012, the first time the U.S. thought Assad’s forces were poised to commit a massacre [there]? Why not in 2013, when the regime barrel-bombed the city for a month straight, or in 2014, when they were talking about a “decisive battle” [as the government tried to encircle Aleppo]?

Tabler: Two things. One is the Russian military intervention, and that the bombing over the last four months has significantly softened up the opposition, and decimated them in many areas. Also, it has led to an exodus of civilians from many of these areas, which weighs heavily on the opposition, which governs many of these different points. That’s the first big change.

The other change is that the Iranians, specifically Hezbollah and Shia militias [backed by Iran], are showing up as part of this Russian push. They were already there, but they have amped up their presence. And that, particularly around Aleppo, has been the ground component. The regime suffers from manpower shortages, so this Russian-Iranian one-two punch has set us on the current trajectory towards the Assad regime possibly retaking Aleppo and areas beyond.

Gilsinan: How does [the Russian air campaign] compare to U.S. and, say, French, sorties over Syria? They’re in different areas.

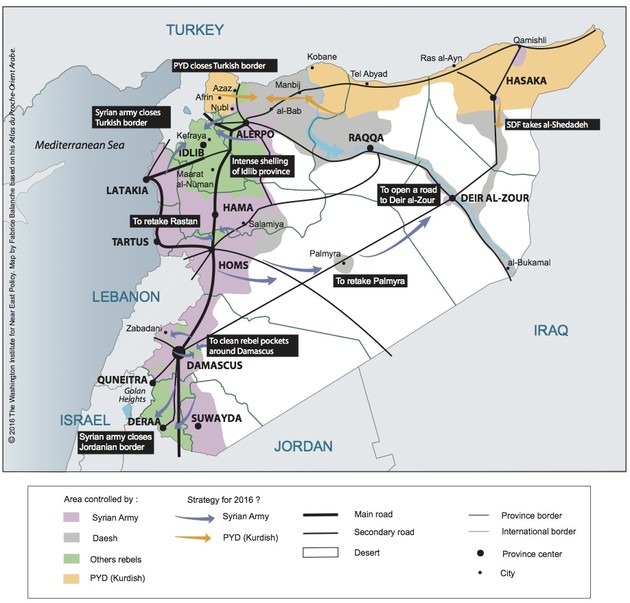

Tabler: U.S. strikes are primarily in the eastern part of the country where ISIS is present. The Russians are the ones who are hitting in western Syria. By [U.S. government] estimates, about 80 percent of their strikes are on non-ISIS targets.

The Russians have been hitting many of the more moderate groups that are backed by the United States. They claim they’re hitting extremists, but [have not launched as many strikes] on ISIS itself. So that has softened up the opposition and therefore led to this operation that we see currently around Aleppo.

Gilsinan: But there are extremists in Aleppo, right?

Tabler: Oh sure, in opposition areas you have [the al-Qaeda affiliate] Jabhat al-Nusra, but you have lots of other formations as well, which are not Jabhat al-Nusra. And some of them are Islamist—I think a lot of the Islamist, or the Salafist groups, the Russians regard as terrorists. We [in the United States] do not. It doesn’t mean we’re aligned with them but we don’t see them the same way.

Gilsinan: So if Assad can retake the city as a whole, can his forces hold it?

Tabler: Well that’s the real question. Until now, the problem for the regime has been that it can’t retake and hold areas, because it doesn’t have the manpower. So those manpower shortages remain, but the change has been that the Russian air strikes have instituted a scorched-earth policy which destroys the area and pushes people out. So when an area’s destroyed, it’s easier to take and hold, because you need less men, because there aren’t any other people there.

Gilsinan: That gets to the next question, which is what the humanitarian effect would be. Specifically, what’s the likelihood of another starvation siege, and how would the scale of something like that in Aleppo compare to what we’ve seen already in [the Syrian town of] Madaya, where citizens are reportedly eating grass and leaves?

Tabler: I think you can expect what we’ve seen elsewhere in Syria, except here it would be much larger in scale—could be upwards of 300,000 who are besieged.

Gilsinan: Which is another way to hold territory, I guess.

Tabler: Well, it is, it’s a way to not have to go in and clean an area. But while it’s besieged, the Russian air force is going to be pounding that area, so there’ll be a lot of death and destruction along the way. It’s just that people won’t have anywhere to go. Except to surrender.

Gilsinan: Would this be the worst single humanitarian catastrophe of the war so far, since [Aleppo is] the biggest city?

Tabler: Potentially. There are other areas around Homs, [in] which we’ve seen similar [humanitarian crises], but maybe not in the same scale because of the population overall. It potentially could be the biggest disaster of the war. We’ll have to see what happens in the coming days, concerning the negotiations, and who gives up and where, and so on.

Gilsinan: If Aleppo falls, walk me through what happens next. First, how would it change the balance of power, within the civil war, between the rebels and the regime?

Tabler: I think it would cement the regime’s hold on “essential Syria”—western Syria, perhaps with the exception of Idlib province [to] the south [of Aleppo]. But basically you would have the regime presence from Aleppo the whole way down to Hama, Homs, and Damascus, and that’s the spine of the country, and that’s what concerns the regime and the Iranians in particular. It would then allow them to free up forces, potentially, to go on the offensive elsewhere, directly into Idlib province, most likely, and then eventually into the south. Then after that they could turn their attention finally to ISIS, which the United States is trying to defeat.

But all of these things would take some time, would take probably months or years to fully institute. But I think that’s what the regime and the Russians are going for: They’re going for a whole-country solution to the Syria crisis based on the Assad regime.

Gilsinan: And then what happens to the regional balance of power within that war?

Tabler: It would be a tremendous loss for the U.S. and its traditional allies: Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Jordan. It’s already been extremely costly for most of those allies, but it would be a defeat [in the face of] the Russian-Iranian intervention in Syria. This would also be a huge loss for the United States vis-à-vis Russia in its Middle East policy, certainly. And because of the flow of refugees as a result of this, if they go northward to Europe, then you would see a migrant crisis in Europe that could lead to far-right governments coming to power which are much more friendly to Russia than they are to the United States. I think that is likely to happen.

Gilsinan: So it changes the entire orientation, not just of the Middle East, but of Europe as well.

Tabler: It will soften up American power in Europe, yeah. And put into jeopardy a lot of the advances in the NATO-accession countries, which are adjacent to Russia, as well.

Gilsinan: That’s a staggeringly significant outcome for relatively cheap [expenditures] on Russia’s part.

Tabler: It is, isn’t it? I don’t think most people get how much of a blowout this really is. I don’t think most people understand: This defeat of the United States by Russia in Syria, it’s not just about Syria. It’s about our presence in Europe.

Gilsinan: That’s an interesting dynamic to me, because you almost wouldn’t have seen it coming, or at least I wouldn’t have, from this direction. Russia wasn’t really able to change the entire orientation of Europe by intervening in Ukraine, say.

Tabler: Right, but this is the result of the American miscalculation that the Syria crisis could be contained. And so we’re seeing now the failure of policy which happened years ago. It’s not just about military intervention in Syria. It is about the failure to create safe areas in order to protect [people] so that they wouldn’t go running for their lives to Europe. And that’s the real tragedy here. And it’s simply because the White House did not believe that the cost was worth it.

Gilsinan: Do you think that that calculation—that the Syria crisis could be contained—obviously it’s wrong in hindsight, but could this have been foreseen, or was it a reasonable gamble at the time that turns out to have failed?

Tabler: No, it wasn’t a reasonable gamble. All the trajectories for displacement of persons, as part of the overall humanitarian disaster generated by the civil war, these trends have been present for years. It’s not that the government didn’t pick them up—many in the U.S. government did. It’s that the decision was to do nothing that involved efforts to protect civilians. There was a decision to support the rebels covertly, there was a decision to try and get a train-and-equip program to fight ISIL, we know all about that, it didn’t go well. But there was no effort to protect civilians inside of Syria, other than to distribute aid in neighboring countries and to try and get that aid across the border.

Gilsinan: What do you think this bodes for the future of humanitarian intervention, or efforts to protect civilians in conflict, or international involvement in other people’s civil wars? Do you think there are lessons here that may be applied for future situations like this?

Tabler: I certainly think “responsibility to protect” is not something that this administration observed. Other ramifications are just the significant weakening of American power. We’re not talking here about the use of force; that’s what was avoided. Power is a lot about perception, about people being able to understand that they can count on you. Do your words matter? And I think in Syria, our words didn’t matter. If you look at it, going back to [President Barack Obama’s call for] Assad [to] step aside, which was read by many to mean that he must go, and I think particularly the red-line incident, the non-strike incident of 2013, that was particularly damaging to American credibility. And I think [it] had ramifications for Russian calculations in Ukraine, and ultimately the calculations of our allies. But we have to understand that this president was elected to get us out of the Middle East. And I think we [Americans] missed that. Because along the way I think he made a lot of decisions on the Middle East which seemed to indicate that he was of two minds. But in the end I think we got the candidate who we originally elected.

The Islamic State of Iraq would not have evolved into ISIL, which would not have evolved into the Islamic State, had it not been for the Syrian Civil War. It generated an unprecedented terrorist threat that we’re only beginning to grapple with now. It also created this humanitarian disaster, which no one seems to fully understand the ramifications of until this point. And I think those two things have made Americans much less safe. And I would point to the testimony [this week] of [Director of National Intelligence] James Clapper about [the risk of] ISIS running its operatives through the refugees. This really, I think, allows ISIS to spread a lot of their terror. And with it, destabilize Europe in the process.

Gilsinan: You mentioned the decline in American power as a result of the Syrian conflict, and I’m wondering if that’s a cause or effect. Is Syria the way it is because American power had already declined?

Tabler: No, no no no. Our economic power ebbs and flows with the markets and with our economic performance. Our military power has not really significantly declined, and that of our combined presence [with] our allies in the region, is far greater than that of Russia. It’s simply as a result of not making decisions at key junctures, not just about the use of force. We were led into this cul-de-sac by the president, where now we are potentially going to stand by and watch the Syrian opposition run into gunfire until the regime runs out of bullets.

This was never about invading Syria. No person that I know of advocated for invading Syria, of all those who advocated for doing more with the opposition. Now we’re in a situation where in order to protect civilians in Syria, we would probably, with our allies, have to invade at least part of the country. But we’re unwilling to do that, of course. So instead the Syrians are left hanging. I just can’t imagine that this is going to make our lives any easier. And it certainly calls into question our very commitment to things like human rights, [punishing or preventing] war crimes, phrases like “never again.” And I think that’s extremely damaging to U.S. credibility and [America’s] reputation in the world today.

Gilsinan: So the actual [physical] capabilities of U.S. power remain the same—it’s influence that you see waning?

Tabler: Yeah. U.S. power, military power and so on, remains, but our willingness to use it has gone down significantly. And I think that’s part of the Iraq War. So if we’re not going to use it, in cases where chemical weapons have been used, [where] we’ve drawn a red line, or there’s a huge humanitarian disaster and we need to protect not just Syrians but also our allies from the results of that, then it begs the question about U.S. military expenditure in general. Why maintain such high military expenditure if you’re unwilling to use it in cases where it’s actually justified? The other part of it is that by demonstrating that we were unwilling to use military force in precise ways at key junctures, we then encouraged others to fill that vacuum. The Russians have been planning this for years, and I’ve spoken with them in Moscow about it.

Gilsinan: Since when? Since 2011?

Tabler: I first saw it in 2014, but it’s been going for a while. It’s the response to what they call “color revolutions.”

Gilsinan: So what were you hearing in Moscow?

Tabler: They believe that the problem is not the Arab uprisings—the problem is the American response to the Arab uprisings. So instead they advocate for something called military-to-military cooperation. Like-minded countries, essentially, work together through their militaries to blast their way out of it. And that’s the way they look at it. And that’s what’s happening right now in Syria. We’ll see if it politically works and so on. And many elsewhere in Europe might see it in similar ways. But what’s interesting is that it’s Russian air strikes that are pushing Syrians out of the country, en masse. So in a way Russia is, with the regime and with the Iranians, playing the role of the arsonist in Syria, and then being heralded as the fireman who comes to put it out. That is really amazing. Because it makes you central to any solution either way. And that makes the world a really chaotic place, and a big challenge, I think, for the incoming [U.S.] president.