For a long time, trans writing meant memoir. From Christine Jorgensen to Janet Mock, the most celebrated trans writers (or more to the point, the only ones who could get published) were those prepared to tell the story of their “transformations” in apparently truthful ways for consumption by a largely cisgender audience.

Big and even medium-sized publishers are still most comfortable putting their money behind true-life stories about “sex change”. But if you dig a little bit deeper, a revolution is happening. It began, perhaps, with the anthologies The Collection: Short Fiction from the Trangender Vanguard and Troubling the Line: Trans and Genderqueer Poetry and Poetics in 2012 and 2013, and has been gathering pace since.

Publishers like Biyuti, Transgenre and Topside (where I work), and magazines like Them, Vetch and Zine of the Trans Poets Workshop are putting out a steady stream of works by trans writers which (unlike I Am Cait or Transparent) are being avidly consumed by trans audiences. They represent a wide and vibrant movement of representation which is not just of us, or even just by us, but for us.

These works go beyond the cliched trans narrative which cisgender network executives and publishers have decided that “general audiences” want. As a result, they have much more to say, not just to trans people, but to everyone. They tell richer and stranger stories, ask deeper questions about gender, identity and injustice, and are written with the kind of brio, inventiveness and excitement that comes from desperately needing to say the things they are finally finding a way to write down.

And a lot of them, maybe most of them, are poetry. This year, for the first time, the Lambda Literary awards will recognize trans poetry as a distinct category. They will have a serious field to choose from.

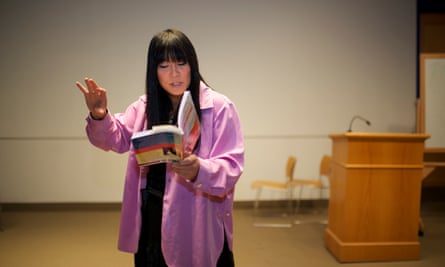

These books are as diverse as their authors. There are passionate polemical slam poets like Dane Edidi and Kay Ulanday Barrett. There are avant-garde academic poets like Trish Salah. There is a school of surreal and emotional hipster verse, centering around Sara Woods and Jennifer Espinoza. And, closest to my own heart, there are attentive lyrical realist writers like Ryka Aoki, Lilith Latini, Tyler Vile and Charles Theonia.

Maybe these writers are too disparate to be a movement. As Salah put it to me: “Our experiences of being transsexual are almost invariably experiences of a lack of mentorship, of a world of writing which doesn’t even imagine trans people, let alone centre us. For a movement, you need common goals and we’re still figuring out what writing is together.” But if they’re not a movement, they are definitely a community.

This is a community which is involved in articulating new ways of being alive for each other. Espinoza told me: “I want to tell my audience something they’ve never heard from a trans person before. That’s why I like poetry – it’s easier to say things that haven’t been put into words before.”

Even the smallest things can be important here. Theonia was told that just seeing an author biography using non-binary pronouns had reduced a reader to tears, and also given them strength to get through a difficult visit with their family.

In fact, it might be precisely that attention to small details that explains this writing’s power. Latini told me that, until recently, “everything about trans people focused around a tragic stereotype. With more recent trans writing it’s different. Performing for a trans audience instead of a cis audience, it’s less about the tragedies of one’s life, but instead the everydayness, the really bittersweet normality of it”.

This representation of the everydayness of trans lives is intensely political. “I didn’t have access to trans writers growing up,” Edidi said to me, “so reading trans writers now, particularly trans poets, is really refreshing. I believe that trans people are revolutionary just by being born, and historically poetry, particularly within the black community, has been used as a form of resistance. There are other sisters of mine causing revolution through art.”

For some writers, resistance is the priority. Latini told me: “I feel, and a lot of other trans women feel, that more visibility is not necessarily better. We have to ask: how can we be visible whilst still controlling our image and taking care of each other, rather than profiting independently? It’s one thing to be visible to others on their terms, another to become visible to each other.”

Certainly for me, as a trans woman, this poetry has changed my life. It has made me feel intensely seen and humanized and at the same time also challenged a lot of my assumptions, and made me beautifully, usefully uncomfortable. But I think the power of this writing goes far beyond the trans community.

As Aoki said to me: “We have to re-establish our place as the visionaries and magic-makers and seers for a civilisation that is in desperate need of us. Ultimately, we are useless if all we do is liberate yourselves. At the end of the day, we’re here to save the world.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion