Meditation

Brain's Response to Meditation

How much meditation does it take to change your brain and relieve stress?

Posted July 31, 2015

How much is enough? This is the question so many people ask when considering a meditation practice. The problem with meditation practice is everyone wants to put in the least amount of time and effort needed to reap the benefits.

During a recent dialogue between western scientists, Buddhist scholars and practitioners on the benefits of meditation sponsored by the Mind and Life Institute, a scientist asked the Dalai Lama what he believes is the minimum amount of time a person should spend meditating to gain the benefits.

He replied most sincerely, “a lifetime.”

Thinking he may not have answered or interpreted the question correctly, another researcher asked the question again. The Dalai Lama replied, again, “a lifetime.” Followed by a jovial giggle that is so characteristic of His Holiness.

One may scoff, thinking it is not practical to become a monk and dedicate one’s life to revealing the ultimate nature of reality and achieve enlightenment. Most people just want to relieve a bit of stress, anxiety and stop the incessant self narrative that occupies one’s mind. Although the answer by His Holiness made most people in the audience laugh at the possibility that practicing an entire lifetime was necessary before achieving benefit, the answer should not be so surprising.

In our theoretical models, (1, 2) by which we propose mindfulness functions as a systematic form of mental training, we break down the process of “selfing” into a successive string of moments that are half a second long. Each half second (500 ms) of your life consists of approximately one quarter (250 ms) non-conscious sensory processing and one quarter (250 ms) conscious evaluation. That means that every moment, your brain and body are processing the world and determining what is (and what is not) relevant to before allowing your conscious awareness to even have the opportunity to interpret what it is you are experiencing!

It is likely that much of your experience is biased towards or away from particular aspects of the world. Over time, these repeated personal moments are conditioned into patterns or mental habits that come to represent your self, how you see the world, and your relation to others. The moments continually shape our entire world view—our hopes, fears, needs, wants, expectations, attitudes, etc., for good or for bad.

For example, on your drive to work, someone cuts you off. What is your first reaction? Do you experience anger? Did you want to flip off the driver? Do you end up mulling over the event and have personal reflections about how you would have responded for the rest of the day? This is not an adaptive reaction and can have negative consequences on your health and future sensitivity to similar stressors.

That singular instance of getting cut off on the road can have a long-term effect on how you react the next time you are stressed, and every time after that. But with meditation, you have the opportunity to become aware of this pattern and condition yourself to react differently. You can learn to let go of negative thoughts, events or interactions. And ultimately, you will be able to perceive and evaluate the world in a way without judgment or reactivity, even when someone cuts you off while driving.

The implication here is that every moment of your life becomes an opportunity for changing your worldview and facilitating a sustainably healthy mind.

From this perspective, every moment (on and off the meditation cushion) has the potential to orient your worldview towards an adaptive perspective and over time - change your mental habits and behavior. One’s entire lifetime is then the mental landscape in which to cultivate and maintain a healthy perspective. You can either fill your mind with destructive thoughts and emotions that are not adaptive each moment or maintain mindful awareness in every moment, thus freeing your mind of obfuscation and increasing more sensory clarity and equanimity towards your self and in relation to the world around you.

With every moment we spend meditating, we have the opportunity to cultivate self-awareness and change how we perceive the world. In fact, the word “meditation” is an English translation of Indo-Tibetan words connoting the cultivation of familiarity with one’s own mind. Meditation gives you the tools to train your mind to be habitual in a positive or adaptive way and reduce all the negative habits or perceptions in your life.

Back to the original question: How much formal sitting meditation is needed to begin experiencing its benefits and have a lasting impact?

As mindfulness and meditation become more integrated into medical models for stress, cardiovascular disease, psychotherapy and more, we must better understand an explicit answer to this question.

The emerging scientific data from the relatively new field of contemplative neuroscience has begun to answer this question realistically and practically speaking. The standard model for delivering mindfulness-based meditation over the last decade has been mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) and related mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs). For more information about MBSR, I recommend checking out some available resources.

The MBI has a particular prescription for 26 hours of in-class guidance (8 classes of 2.5 hours) and 45 minutes/day of daily home practice. The types of meditation are also very specific, including: focused attention meditation, open monitoring meditation, body scan and some light Hatha yoga. For the full description of these practices, and in more detail theoretical models (1, 2, 3, 4) have been created to guide future research. Many studies are beginning to adapt the MBI model – delivering mindfulness-based meditations for various clinical applications (e.g., anxiety, depression, chronic pain, etc.) – using a range of styles and training requirements in delivery. For example, the typical model for a MBI involves a weekly in-class format with home practice requirements, but some research has also been testing short-term, intensive retreats over a few days as well as long-term silent retreat settings that could last 10 days, 3 months or longer.

Furthermore, in today’s world, technology and social media are driving forces for our socio-cultural evolution; thus, mobile apps are now beginning to dominate the market place to augment in-person group formats and facilitate home practice. Mobile apps like Headspace, DeStressify, Mindfulness, Calm, etc., have been successful in this context and it remains an empirical question to what extent these apps are sufficient on their own in comparison to the standard MBI.

One particular difficulty in interpreting the findings is the great variability of the context by which the content is delivered.

The way in which we practice meditation can be varied. For example, in one situation, an individual may spend 1.5 to 2 hours meditating outside of the home in a group setting, and then return to his or her everyday stressors. The impact and effects of meditation may vary greatly for this individual versus someone who completes a retreat where meditation practice is much more frequent, the duration of practice is longer, and thus, the continuity and intensity of practice is much greater.

Some studies have reported neuroplasticity in response to painful stimuli after as little as four 20-minute meditation sessions. Some mindfulness intervention studies claim to use mindfulness induction techniques (example), which could be as short as a one moment of paying attention to present sensory experience, non-judgmentally and non-reactively. Such use of mindful awareness would be considered to be very low in intensity and continuity (see below). Many of the studies out there involve differences between clinical and non-clinical samples, while others involve a cross section of meditators with varied levels of experience.

Contextual differences abound, and one must also consider the variability in goals, content and process by which the meditation practices are being delivered. Stress reduction is a very different goal from enlightenment, yet if the content and process of delivery is the same, outcomes may be very similar. The field is young and much is left to be investigated.

Upon interpreting any of the scientific data that comes out reporting benefits of meditation, there is one fundamental process outcome we must keep in mind: like learning any new skill, the more we practice the better we become. The more you meditate, the more efficient your brain becomes at meditating. This will make more sense below, when I describe the brain regions affected by meditation practice.

What parts of my brain are changing in response to meditation? And why are these regions or brain networks important for my health and well-being?

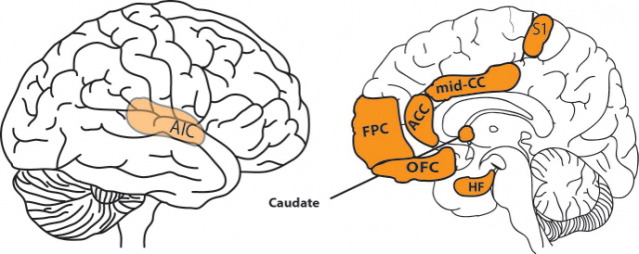

As reported in a series of recent review articles that statistically analyze all the neuroimaging papers on mindfulness (1, 2, and Fox et al. in prep), and in the highest impact paper to come out on mindfulness meditation research across contexts, meditation affects multiple regions of an individual’s brain with some consistency, eight in particular. It can affect the size, shape and even the function of these areas of the brain: the frontopolar cortex, the sensory cortices and insula, the hippocampus, the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), mid-cingulate cortex, orbitofrontal cotex and the caudate nucleus.

One analysis examined 21 neuroimaging studies that included approximately 300 meditation practitioners from varied traditions and varied levels of expertise. Five studies included involved short-term training that varied between as little as 5 hours to as much as 60 hours of formal practice time. The other studies involved long-term practitioners with at least thousands of hours of formal meditation experience. In the interpretation of these findings, one must also keep in mind that no brain region ever functions alone, but rather functions in complex networks. When neuroimaging results compute complex statistical analyses, we often get the picture that one particular region is running the whole show. This is a gross failure in interpretation. Rather, these functional activations more often represent major hubs that are associated with the activation of larger networks.

Meditation affects my cauda-what?

The region known as the caudate nucleus is a subcortical part of the brain that manages skill learning and automatized cognition, and it may see some of the most profound changes due to meditation.

This is the area of a brain that holds on to skills and lessons you have learned, so when you go to repeat them they are second nature and you can perform a task without having to think about it. Take riding a bike for example. When you hop on, you do not want to have to think about the bike, pedaling or having your fingers on the brake; you just want to get on and ride. When you are able to react or function without thinking about the task at hand, this frees up much of your cortex, to allow your cognitive resources to react more rapidly and efficiently when other things happen, like if there’s a bump in the road and you need to navigate your bicycle around it while also navigating around traffic. (Whether you hit the bump and fall off is not the caudate nucleus’ fault….it could be more to do with filling your mind with fear and/or active evaluation/interpretation that knocks you out of that zone.)

It is often the case that high-performance athletes engage the caudate and associated basal ganglia circuitry to be and stay in the zone or flow without being distracted by fear or interpretation of such fear. See a TED talk by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, who has written extensively about FLOW.

Ultimately, meditation may help the caudate nucleus and associated circuitry create more temporal space for your brain to be efficient and promote better brain-mind-body function. This allows for fluid performance during task demands, while in the face of life stress, thereby conditioning the moments of selfing to define a new version of YOU; one that is adaptive and flourishing. In my next post, I hope to explain some of the meaning behind changes in the other brain regions.

So, how much meditation time is necessary to achieve some benefit? Well, a lifetime of practice is ideal – but every moment helps.

How do I get started?

One easy way to begin practicing meditation is through guided practices on a user-friendly app such as DeStressify, a simple and effective way to manage daily stress. Making a commitment to meditation is the best way to experience the long-term benefits. With DeStressify, the practices are built with a busy lifestyle in mind and integrate daily reminders to notify you when it is time to practice meditation.

There are many other apps on the market now and I encourage you to check them out as well as their reviews (and here). Silicon Valley is also getting in the game and developing the hardware to advance practice with neurofeedback (see companies like Interaxon, Brainbot and Palo Alto Neuroscience). Every moment helps, and every moment presents the opportunity to change your brain and your perspective.

References

Vago, D. R., & Silbersweig, D. A. (2012). Self-awareness, self-regulation, and self-transcendence (S-ART): a framework for understanding the neurobiological mechanisms of mindfulness. Front Hum Neurosci, 6, 296. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00296

Vago, D. R. (2013). Clarifying Habits of Mind: Mapping the Neurobiological Substrates of Mindfulness through Modalities of Self Awareness. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1-15. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12270

Holzel, B. K., Lazar, S. W., Gard, T., Schuman-Olivier, Z., Vago, D. R., & Ott, U. (2011). How Does Mindfulness Meditation Work? Proposing Mechanisms of Action From a Conceptual and Neural Perspective. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(6), 537-559. doi: 10.1177/1745691611419671

Gard, T., Noggle, J., Park, C., Vago, D. R., & Wilson, A. (2014). Potential self-regulatory mechanisms of yoga for psychological health. [Hypothesis & Theory]. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00770

Tang, Y. Y., Holzel, B. K., & Posner, M. I. (2015). The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nat Rev Neurosci, 16(4), 213-225. doi: 10.1038/nrn3916

Sperduti, M., Martinelli, P., & Piolino, P. (2012). A neurocognitive model of meditation based on activation likelihood estimation (ALE) meta-analysis. Conscious Cogn, 21(1), 269-276. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2011.09.019

Fox, K. C., Nijeboer, S., Dixon, M. L., Floman, J. L., Ellamil, M., Rumak, S. P., . . . Christoff, K. (2014). Is meditation associated with altered brain structure? A systematic review and meta-analysis of morphometric neuroimaging in meditation practitioners. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 43, 48-73. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.03.016

Fox, K.C.R., Dixon, M.L., Nijeboer, S., Girn, M.,, Floman, J.L., Lifshitz, M., Ellamil, M., Sedlmeier, P., & Christoff, K. (in preparation). Functional neuroanatomy of meditation: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 78 functional neuroimaging investigations of meditation states. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews.

Yusainy, C., & Lawrence, C. (2015). Brief mindfulness induction could reduce aggression after depletion. Consciousness and Cognition, 33, 125-134. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2014.12.008