On 4 December last year, the London Underground ingested 4,821,000 passengers and spat them out at their destinations, and in doing so set a new record for a single day. If you paused to contemplate this for a moment, you might think of all those Oyster cards tapping, all those doors sliding, all those people moving, consider whatever mad visionary first thought of demolishing houses to dig holes in the ground to put trains in, and conclude that a subterranean public transport network is a small miracle. Most of the time, though, commuters don’t pause, and don’t conclude anything of the sort. They have other things on their mind. To many of them, “a small miracle” might seem more like a description of their journey to work than of the system that facilitates it.

In the execution of their own daily miracles, London’s commuters have learned to withstand vast and unpredictable challenges: track closures; signal failures; engineering works. And they have developed a thick skin. But on that particular Friday, the 11,000 of them who got off at Holborn station between 8.30 and 9.30am faced an unusually severe provocation. As they turned into the concourse at the bottom of the station’s main route out and looked up, they saw something frankly outrageous: on the escalators just ahead of them, dozens of people were standing on the left.

We might be bad at dancing and expressing our feelings, but say this for the British: when we settle on a convention of public order, we bloody well stick to it. We wait in line. We leave the last biscuit. And when we take the escalator, we stand on the right. The left is reserved for people in a hurry. In Washington DC, those who block the way are known as “escalumps”; here, they can expect the public humiliation of a tutting sound just over their shoulder. “Passengers just don’t like having these things changed,” says Celia Harrison, a Transport for London (TfL) customer strategy analyst, and one of the key people responsible for this heretical deviation from the norm. “I’ve worked on stations for many years. So I was aware that whatever we did people weren’t going to be comfortable about having their routine disturbed.”

The idea had come about after Len Lau, Vauxhall area manager, had gone to Hong Kong on holiday. Lau noticed that passengers on that city’s Mass Transit Railway (MTR) were standing calmly on both sides of the escalator and, it seemed, travelling more efficiently and safely as a result. His report prompted Harrison and her colleagues to wonder whether the same effect would apply at a station such as Holborn, and so they set about arranging a three-week trial.

The theory, if counterintuitive, is also pretty compelling. Think about it. It’s all very well keeping one side of the escalator clear for people in a rush, but in stations with long, steep walkways, only a small proportion are likely to be willing to climb. In lots of places, with short escalators or minimal congestion, this doesn’t much matter. But a 2002 study of escalator capacity on the Underground found that on machines such as those at Holborn, with a vertical height of 24 metres, only 40% would even contemplate it. By encouraging their preference, TfL effectively halves the capacity of the escalator in question, and creates significantly more crowding below, slowing everyone down. When you allow for the typical demands for a halo of personal space that persist in even the most disinhibited of commuters – a phenomenon described by crowd control guru Dr John J Fruin as “the human ellipse”, which means that they are largely unwilling to stand with someone directly adjacent to them or on the first step in front or behind - the theoretical capacity of the escalator halves again. Surely it was worth trying to haul back a bit of that wasted space.

Paul Stoneman, one of Harrison’s colleagues, did some preliminary calculations. In theory, he found, getting people to stand on both sides would mean that 31 more passengers would get on to the escalator each minute – an increase of 28%. Holborn seemed like the perfect test case, not only for the rake of its escalators, but also for its rush-hour stampede: “When you come round the corner and see this throng,” says Stoneman, “you just go, blinking flip, I don’t want to use this station, it’s a nightmare. It’s like Bank.” But success was by no means a given: as Lau also noted, commuters in Hong Kong are vastly different to British ones. In a wash-up meeting to analyse the results of the trial a few weeks after it was completed, Stoneman asked the dozen people in the room: “How many years have we been saying, ‘stand on the right’? It’s quite a significant behaviour to change.”

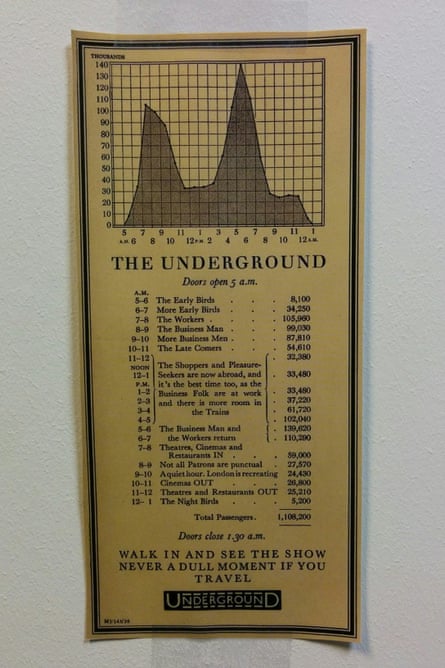

Hard though it might be, changing how commuters behave is an ever more important part of a barrage of efforts to increase the capacity of the Tube, efforts that draw in equal parts on social psychology and fluid dynamics: the best model for the movement of a crowd through a warren of tunnels is the movement of a torrent of water through pipes. London is growing faster than any other European city; its population of 8.6 million is expected to hit 10 million by 2030. The London Infrastructure Plan 2050 predicts demand on the system to rise by 60%. And so TfL has to extract every last ounce of capacity from its underground network, the oldest in the world. A 1928 poster on display at the London Transport Museum and TfL headquarters charts the flux in passengers through the day - “The Workers”, “The Businessman”, “The Shoppers and Pleasure-Seekers” – and adds them up to a hefty 1.1 million, a total so large that the copywriter boasts: “WALK IN AND SEE THE SHOW/ NEVER A DULL MOMENT IF YOU TRAVEL UNDERGROUND.” That mass of people was still less than a quarter the size of last year’s average load.

To keep up with that growth, huge investment is needed, and major works are nearly always being carried out: as the Holborn trial went on, the £500m upgrade of Tottenham Court Road was being completed one stop away. In a system operating so close to capacity, the obedience of its users is also vital. “If everybody wasn’t so compliant in their journey,” says Stoneman, “it would be a fistfight down there.” And so, with so much at stake, decisions to wind up commuters are not taken lightly: there is serious analysis behind them.

The stand-on-the-left controversy is no exception. Harrison, Stoneman and their colleagues believe it could make a noticeable impact on congestion at some of London’s busiest stations, congestion that will only get worse as train design, frequency and reliability improve, as the trains get faster and the doors get bigger, and ever more passengers are dumped on the platform at a time. “From my point of view,” says TfL’s head of transport planning Geoff Hobbs, “the ideal train would look like a bread bin”.

In order to make their plan work, they had to be ingenious – and persuasive. “Originally, we thought enforcement might be a good idea,” Harrison told colleagues at the wash-up, “as in people standing on the left in uniform, so that people couldn’t walk past them. But after concerns about possible assaults were raised, we decided it wasn’t that good of an idea. So we went for encouragement.” That meant teams of staff standing at the bottom of the escalators with loudhailers, asking commuters, as cheerfully as possible, if they would mind standing on both sides. It mean plain-clothes “plants” – “great, big lift engineers,” according to Stoneman – being sent up the escalators to block the way for others and create a new sort of social pressure. It even meant asking amenable couples to hold hands across the escalator, the better to thwart those who wished to slalom through the line.

Harrison is a 16-year veteran of the Underground, and even if she mostly cycles herself, she loves it, above all for the people. For the best part of two decades, she has absorbed everything a global city can throw at her – from the mundane intensity of rush hour to the seismic shock of the 7/7 attacks, when, as station supervisor at Aldgate, it fell to her to call for ambulances after the bomb went off. Through it all, she says, she has remained an optimist, and perhaps she has a better sense of perspective than most. Last month, as she stood on the concourse with all those good ideas up her sleeve and watched the trial unfold, she was a little unprepared for the intensity of the reaction, let alone for the interest of newspapers such as Denmark’s Politiken or the Washington Post. During the three weeks of the Holborn project, those who disapproved of the idea voiced their opinions with alacrity, as a preliminary internal report diligently records. There were plenty who didn’t seem to hate it, too – but they were rather quieter.

“This is a charter for the lame and lazy!” said one. “I know how to use a bloody escalator!” said another. The pilot was “terrible”, “loopy,” “crap”, “ridiculous”, and a “very bad idea”; in a one-hour session, 18 people called it “stupid”. A customer who was asked to stand still replied by giving the member of staff in question the finger. One man, determined to stride to the top come what may, pushed a child to one side. “Can’t you let us walk if we want to?” asked another. “This isn’t Russia!”

It is not yet clear whether a Putinesque future awaits us. If the stand-on-the-left experiment is to be adopted permanently at Holborn, and potentially be extended to other comparable stations, it will have to get through more testing and analysis. What could politely be termed “customer feedback” has already led the team to conclude that it would be wise to keep at least one escalator running conventionally. But the preliminary evidence is clear: however much some people were annoyed, Lau’s hunch was right. It worked. Through their own observations and the data they gathered, Harrison and her team found strong evidence to back their case. An escalator that carried 12,745 customers between 8.30 and 9.30am in a normal week, for example, carried 16,220 when it was designated standing only. That didn’t match Stoneman’s theoretical numbers: it exceeded them.

These results, you might imagine, would be enough to see the model introduced instantly at any station where the escalator was sufficiently steep to discourage people from walking up. But there’s a problem: those damn commuters. With the constant (and unsustainable) attention of staff, and three weeks of practice, they eventually became a little more docile, and followed the new regime, satisfying themselves, as the report puts it, with a “great deal of non-verbal communication in the form of head-shaking”. The following week, they immediately went back to normal. And so another trial is under discussion. “It’s like child psychology,” says Stoneman, a father. “It takes four days to get your kid to go to bed and do what it’s supposed to do, and it takes one day for them to stay up, and you’re sitting there banging your head against the wall again.” So if you can’t tell them what to do every two minutes, how on earth do you get them to comply?

At the wash-up meeting in the faded grandeur of TfL’s office at St James’ Park station, this question was the subject of careful scrutiny. The next trial, if it happens, will focus on one escalator alone; it will investigate whether customers can be persuaded to stand without loudhailer-brandishing staff to monitor them. The handrail and tread of the escalator will be a different colour, and firmly planted pairs of feet will decorate the left of the steps. In lieu of actual people, a hologram customer service operative will remind people to stand on both sides.

Then there’s the question of exactly what the hologram should say. Some argued for an appeal to altruism. Said Stoneman: “If the understanding is, we’re doing this for the greater good, people will comply.” Then it was pointed out that in the run-up to the Olympics, when everyone was panicking that the Tube would be hopelessly oversubscribed, the team tasked with encouraging people to take alternative routes had hit on the opposite insight: “It wasn’t about saying you’re taking one for team London,” said communications manager James Grant. “It was about saying, you’re benefiting from the journey yourself.” So what’s the slogan? Stoneman cast around for a moment. “It’s a perception of being held back, but you’re not really,” he said. “So … this is benefiting you, your individual time is reduced, but you are relinquishing the right, if you wish to, of walking on this escalator.” There was a pause. “Right,” said Grant Dyer, another of the report’s co-authors. “We’ll try to make that snappier.”

Perhaps it’s a shame that the appeal to altruism tends to prove less effective, but Harrison doesn’t find it terribly surprising. “People would be shocked if they knew how complicated the whole system is,” she says, a week or so after the meeting. “How difficult it is to run a service every two minutes, and control crowding, and work around equipment failures.” Since she started on the tube herself, she has amended one important bit of her commuting etiquette: she doesn’t run for trains as the doors close any more. “On the Jubilee line, if they have to reopen the door because you’re caught, that’s a 30-second delay. And then you have a gap in front, and a knock-on effect, and it gets bigger and bigger, and before you know it, there’s a five-minute delay going through central London. But I was in the habit, and it took me a good month or so to stop myself doing it. How are you going to stop the customers who don’t even understand?”

And yet, recalcitrant though commuters can be, Harrison retains a faith in their reason when it really counts. She remembers how they left the station after the bomb went off at Aldgate: “It was one of the most striking aspects of the day. People doing exactly what we asked them to do, which was leave – really calmly, completely unselfishly, helping each other. And this quality of silence.”

On any given morning at Holborn, the atmosphere is, happily, almost the exact opposite. And perhaps that tumult is the price and the pleasure of living in a great city. Do Londoners have it in their nature to stand on the left? It’s too early to say. Change is hard. Still, as I arrived on a Victoria line platform shortly after speaking with Harrison, and I heard the tell-tale beep of a train getting ready to depart, I surprised myself. I didn’t try to squeeze aboard. Another one, after all, will be along in a minute.

The world underground

The standing to the right rule, first promoted in Britain, is not mirrored all over the world: Shanghai residents take a strictly optional approach; Australia is a notable rogue, preferring escalator users to stand to the left; and the rules are different in different Japanese cities (left in Tokyo; right in Osaka).

Escalator users in Hong Kong and Japan have seen campaigns encouraging them to stand on both sides of the escalator: “Let’s All Grab a Handrail,” and “Don’t walk. Stand where you like.” But results have been mixed – etiquette seems still to be trumping rules.

Leaving your paper behind on the train in London might be seen as a courtesy, but in Vienna it’s not the done thing – authorities are actively encouraging people to adhere to this piece of etiquette with signs and announcements.

In Japan it’s considered polite to switch your phone to “Manner Mode” (an excellent way of describing what we might think of as “silent”) when using the metro, so that other passengers aren’t subjected to ringtones galore as they travel.

Eating durian fruit, considered the world’s smelliest, is a terrible faux pas on Singapore’s MRT, and has been banned by authorities – “no durian” signs have been posted around the network.

It’s considered bad manners to sit in priority seats in Seoul subway carriages at any time, regardless of whether there’s anyone around who needs them – you can expect multiple chiding looks. Ellie Violet Bramley

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion