Arguably, no one alive has researched the history of the American bar and its keepers more thoroughly than David Wondrich, the author and cocktails columnist for Esquire magazine. Today, The Bitter Southerner is proud to turn the Good Dr. Wondrich loose amid the deep history of how African-Americans of the late 19th century gained esteem behind the bar and how their experiences were very different in the North and South — in ways that might defy your assumptions.

In 1892 Frank Beck, a longtime bartender, opened the Atlas Hotel in Cincinnati. With just 18 rooms, it wasn’t much of a hotel. But with a location right around the corner from the hulking new City Hall, and furnished with a large and ornate barroom, it didn’t have to be, either. Indeed, on its opening day the bar served 3,000 people. But unfortunately for Beck, his head bartender turned out to have a bad habit of neglecting his duty, and in early 1893 Beck let him go, replacing him with Louis Deal, one of his waiters. Deal was a “clean and polite and honest” young man and had worked as a bartender before. Beck was more than pleased with his choice.

“Deal did his work better and was more satisfactory than any man who had ever held the place,” he told a reporter from the Cincinnati Enquirer, adding that “so long as he did his duty he intended to keep him where he was.”

The reporter was there because Beck was white, his bar catered to a white clientele, and Deal was, as the Enquirer put it, “a fine looking young colored man.” The city’s (white) bartending community had objected strenuously to Deal’s employment and managed to talk a large part of Beck’s clientele into a boycott, and suddenly the saloonkeeper had a big fat (and newsworthy) problem on his hands. Beck held out for another week. Then George Bear, head bartender at the prestigious Gibson House and “one of the best known white barkeepers in the city” sat him down and gave him an ultimatum:

He could either discharge Deal or the barkeepers of the city (or at least the more prominent ones) would issue 100,000 dodgers [i.e., flyers], which they would distribute around the city, calling attention to the fact that the Atlas Hotel was the only first-class establishment in the city that employed a colored man as a regular barkeeper.

Two days later, Beck let Deal go. It didn’t do him any good: Within two months his place was closed and sold at auction. Deal went back to being a waiter, which didn’t seem to bother anyone. Bear kept mixing drinks at the Gibson House.

A couple of months after the Deal debacle, “the Old Sweet,” as the West Virginia resort of Sweet Springs was known to its patrons, opened for the summer as it had done for every year since 1833, the war ones excepted. A summer haven for Virginians of the likes of Robert E. Lee, it offered genteel company and blessed relief from the summer swampiness of Richmond and Tidewater Virginia. It also offered John Dabney, who was as usual dispensing his characteristic “‘What will you have, sir?’” with “entire satisfaction.” In this case, the drinks were Mint Juleps. A Lexington, Kentucky, journalist encountered one of them in 1894:

The julep a la Dabney is a world-wide art bestowed upon personages whom he holds in high esteem. They are prepared in a sterling silver goblet 14 inches high, and imbibed through solid silver straws. The cup, of a quart capacity, was made for Dabney, and bears upon its bowl the legend, “John Dabney, presented by the gentlemen of Richmond for champion juleps.”

Dabney, then 73 years old, was born a slave in 1824. He would mix Juleps and, eventually, cater excellent suppers for wealthy white Richmonders from before the Civil War until his death in 1900. And if he was treated with queasy-making condescension in the process — the Kentucky journalist dubbed him an “old uncle” who is “a picturesque figure of the past” and added that “his skin is dark, but there beats in his bosom a whiter heart than is sometimes found in persons whose skin is of a lighter hue” — he was at least able to work, and work profitably, at his trade.

For the past 15 years, I’ve managed to make a living out of researching the histories of old-time bartenders and their drinks and celebrating them in print. As jobs go, it’s a fun one — particularly when compared to my previous one, junior English professor. But my “work product” (as the lawyers call it) is pretty lightweight stuff: Most publications that are willing to print a piece about historical tippling want an amusing anecdote or two and then a recipe, not a clear-eyed look at serious social issues — or even a bleary-eyed one, for that matter. If there’s a bartender in the piece, he should be a character with a fine moustache, a twinkle in his eye and a knack for waltzing the booze around with ice. And if his other activities include organizing racists to hound a young man out of his job, well, the less said about that the better.

Yet I truly do believe that the traditional American art of the bar — the art of mixing individual iced drinks to order from a wide array of spirits, wines, juices, syrups, bitters, herbs and so forth — is one of the glories of our popular culture, something that can hold its head up alongside the other American “lively arts,” as Gilbert Seldes labeled them back in the 1920s: jazz, movies, comics and such. Judging by the broad-based renaissance recent years have seen in the craft, I’m far from alone in that opinion. But if mixology (for want of a better word) is going to stand with the other lively arts, its place in American life will have to be properly understood, and that requires looking at it as it was, not as we might like it to be.

Which means coming to terms with episodes like our Cincinnati one, and trying to understand why John Dabney didn’t face the same treatment.

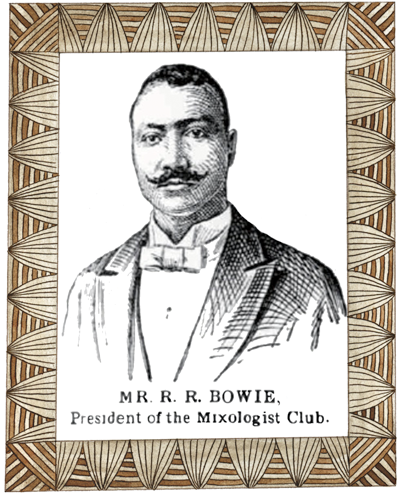

Black people have been mixing drinks in America since the earliest days of European colonization. After the Revolution, saloon-keeping was one of the few occupations open to free blacks in America, and any part of the country with a significant free black population had black-owned saloons to cater to it. These were generally ignored by the black press as not leading to the improvement of the race, while the white press only turned its attention to them when something occurred in one that would elicit fear, outrage or derisive laughter from readers. Like white saloons, black saloons came in all sorts, from buckets of blood such as New Orleans’ Steamboatman Exchange, where gambling and knife-fighting were the orders of the day, to lively neighborhood joints such as Bill Curtis' Elite Social Club in St. Louis (which, despite being the place where Stack Lee shot Billy Lyon on Christmas night, 1895, was on the whole a square and orderly joint) to high-toned establishments such as Moore and Prioleau’s Sparta Buffet and the elegant Metropole Club, both in Washington, D.C. (In 1898, R.R. Bowie, J. Burke Edelin and a posse of that city’s other leading black bartenders even founded an exclusive “Colored Mixologists Club.”) In practice, these saloons generally could not exclude white patronage, and one finds frequent accounts of groups of young white rowdies tearing it up in black establishments, particularly in the less elegant ones.

The converse did not of course apply: White saloons were for white people, and blacks could not drink in the vast majority of them. If they tried, when they weren’t outright ejected they were refused service by the bartenders, charged prohibitive prices — on the order of $10 for a 15-cent cocktail — or otherwise passive-aggressively fucked with until they left. Even when New York State passed an equal accommodations law in 1895, after a brief spate of black drinkers sighted in the barrooms of the city’s great hotels, or at least the minority of them that actually obeyed the law, things soon went back to normal.

There were also, to be sure, the so-called “black and tans,” saloons where the clientele was racially mixed. But these — the proprietors could be black or white — were found only in the roughest urban neighborhoods or out on the frontier and were with few exceptions neither respectable, nor even minimally safe, for patrons of any race.

That leaves the saloons like Beck’s, where black bartenders served a white clientele (I have yet to come across an example of a saloon where white bartenders mixed drinks for an exclusively black clientele). A few of these — a very few — were even black-owned, such as the famous Cato’s Tavern, a New York City fixture from the early 1810s to the 1840s (you can read about Cato Alexander, its proprietor, here). Not that there were many white-owned ones, either, not if you look at places like Chicago and Boston and Buffalo and New York. When Beck told the man from the Enquirer that “there are colored barkeepers in Cleveland, Chicago, Columbus and other cities,” he might have been technically accurate, but only just. In New York, if, back in the 1870s, you had been able to gain admittance to the great Irish-American sporting figure John Morrissey’s political clubhouse, you would have had a chance to taste Washington “Wash” Woods’ famous rum-brandy Punch. Up the Hudson River in Albany, the politicians drank at Adam Blake’s Congress Hall; his father had been a slave to Stephen Van Rensselaer, the Revolutionary War general. There were a smattering of other black bartenders throughout the Northeast and Midwest. Al Strickland, at Charles Shere’s saloon in Indianapolis, was typical, in that in 1891 he was in a position “held by no other colored young man in the city.” Their acceptance was grudging at best and at worst — well, there’s the 1893 episode from the Milwaukee suburb of Cudahy, where the town’s ex-supervisor put Benjamin Skeeckels, a “perfectly harmless” young black man, behind the bar at his saloon, only to see the “not over smooth element” of town attempt to lynch the man. Skeeckels escaped by the skin of his teeth, upon which his tormentors demolished the saloon.

But that was the North. Dixie did things very differently indeed: Mr. Dabney was no aberration. Sure, at any time except during the very height of Reconstruction, when equality laws were enforced at gunpoint, a black man would not be served in a white bar. Yet black bartenders in such establishments were not only tolerated but often even celebrated. That had nothing to do with Reconstruction: indeed, it went back to the early days of the Republic. In Virginia, the tradition was particularly strong. In Richmond, the Quoit Club, which brought together 30 of the city’s leading citizens (including, e.g., Chief Justice John Marshall of the United States Supreme Court) every other Saturday from May to October to toss quoits, eat barbecued pig with cayenne and drink porter, Mint Juleps and the Club’s Punch, had Jasper Crouch to preside over all the catering and cooking. A black freedman who was acknowledged for his particular and unparalleled expertise in Punch-making, he had, as Samuel Mordecai recalled in 1856, “acquired the gout in this congenial occupation, and also the rotundity of an alderman.”

Other celebrated black Virginia mixologists made their reputations while still slaves. John Dabney, enslaved to the De Jarnette family, achieved such a reputation while mixing Mint Juleps in Richmond that he was acknowledged as (according to the Richmond Times) the city’s “cunningest compounder of beverages, and the most skilful architect of pyramidal adornments and floral and fruity garniture” (the Antebellum Julep did not fuck around when it came to garniture, and nobody invested as much in it as did Virginia’s black mixologists). That reputation made him money: enough, in fact, to purchase his and his wife’s freedom. The saloon he ran during the Civil War, until the Confederate government closed such establishments, was the finest in town. His only rival in concocting elaborate Juleps was Jim Cook, also a slave. In 1860, when the Prince of Wales visited Richmond during his American tour, the city fathers put Cook forward to construct him one (or two, or three — accounts differ) of his ornate, even architectural multi-serving Juleps. Cook’s Julep(s) would prove to be the Prince’s fondest memory of the city.

The most successful of Virginia’s black mixologists, however, did his work not in Virginia proper but in Washington. Richard Francis, known universally as Dick or “Uncle Dick” (there’s that dickish “Uncle” again) was born in freedom to free parents in Surry County, Virginia, in 1827. By 1848, he was in Washington, at Andy Hancock’s small, ramshackle and curio-filled bar on Pennsylvania Avenue, not far from the White House. He would work for Hancock and then his son for some 35 years, through war and Emancipation and one administration after another, mixing drinks for senators and congressmen and cabinet secretaries, for touring actors, literary lions and other celebrities. And not just mixing drinks for them — after all, he was a bartender, not a Julep-making robot. He conversed with his customers, cultivated his regulars, got to know them. As one old-timer recalled in 1903, “he could count friends among the whites by scores and hundreds.” Among them were such dignitaries as Daniel Webster, Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun. In 1884, another of his friends, President pro tempore of the Senate George F. Edmunds, made sure that when the lucrative position of managing that institution’s private restaurant came open, Francis got it. He would die four years later, an illiterate bartender who was able to leave his family a fortune in Washington real estate. And by the time he died he was able to see his son in possession of a medical degree from the University of Michigan and sitting on the city’s school board.

The Southern tradition of employing black men behind the bar continued after Emancipation, as we’ve seen with John Dabney’s career. Not everywhere was as open to it as Virginia and Washington, but one can nonetheless find examples from most Southern states, from Georgia and the Carolinas to Louisiana and Texas and on up the Mississippi as far as St. Louis, where, for example, Tom Bullock (a Louisville native who had tended bar at the tony Kenton Club there) presided over the bar at the exclusive St. Louis Country Club and, in 1917, published the first cocktail book written by a black bartender. Black bartenders were also common on the riverboats that were such a feature of life on the Mississippi.

Some of these men often not only prospered to a degree not permitted to the vast majority of black people at the time, but also earned the respect and even affection of their white patrons. In this, too, New York’s Cato Alexander was a pioneer: When he married Eliza Jackson in 1828, the New York Evening Post added the following verses to its brief notice of the event:

Cato the great has changed his state,

From single to that of double;

May a long life with a Jackson wife

Attend him void of trouble.

I have yet to come across another contemporary example of the paper treating a black New Yorker with actual human warmth. A generation later, when Jasper Crouch “fell a victim to the good things of this life” (as Samuel Mordecai put it), the Richmond Light Infantry Blues, the high-society militia for whose gatherings he also made Punch, appointed a committee to give him a proper funeral and headstone. When, a couple of generations after that, Dick Francis died, one Washington insider observed that “although he was never engaged in public life, he was probably better known personally among the noted men of the country than Frederick Douglass” and listed his many famous friends. And when Tom Bullock published his “Ideal Bartender,” it bore an introduction written by George Herbert Walker, President George Herbert Walker Bush’s grandfather. (“It is a genuine privilege to be permitted to testify to his qualifications for such a work,” quoth Walker.) In 1897, the actor Burt Clark, who played the stereotypical Southern Colonel in many a Broadway show, recalling John Dabney’s Juleps, claimed that their maker was “as much a credit to the South as the Washington and Lee University,” adding that “Richmond idealizes him. Virginia is proud of him. The South honors him.”

I don’t want to imply with any of this that it took this white approval to validate these men’s existences. In fact, I believe it was quite the opposite: The affection and respect they elicited is one of the few signs of humanity exhibited by a grindingly inhumane system, and it’s a particular irony that their clientele included many of that system’s biggest stakeholders. When Emancipation was finally brought to Richmond by force of arms, John Dabney, who had purchased his freedom on credit, was released from the remaining $200 of his debt. He paid it anyway, insisting when his former master tried to return the money that he had been taught to pay his debts. I’m sure he was very polite and obliging about it, but it’s hard not to view his gesture as a raised middle finger.

Both before and after the Civil War, these men led precarious lives and held their positions at the suffrage of a petty, capricious and all too often violent white majority. Back in 1835 Beverly Snow, another bartending Virginia freedman whose Epicurean Eating House had introduced elegant drinking and fine dining to Washington, let loose some mildly censorious remarks about the behavior of the “wives and daughters” of some of the city’s white “mechanics,” or working men, and lost his house and his business and very nearly his life in the rioting that ensued. He was lucky: In 1907, in the southern Arkansas town of McGhee, Sam Fleming got in an argument with his white fellow bartender. The argument led to blows, Fleming gave the man a thorough thrashing and was arrested for his pains and thrown in jail, whereupon “a party of masked men removed the hinges from the jail door, took Fleming out and hanged him.”

Those who avoided trouble did it at what must have been a serious cost to their pride and humanity. When Lexius Henson, who ran the most opulent saloon in Augusta, Georgia, had to tell the group of well-dressed black men who came into his place one day in 1875 that it was “a white man’s bar, and they ought not to try to injure his business” by drinking there, that must have extracted a price. But running that business exacted its own toll. “If you ever expect to get money or anything worthwhile out of a white man,” Dabney’s son Wendell Phillips Dabney (who would go on to attend Oberlin and become one of the pioneers of the Civil Rights movement) recalled his father telling him as a child, “always make him feel that he knows more than you and always act as if you think he is the greatest man in the world." Wearing the genial mask of the host, no matter how provocative, even inhuman, the guest, can be an intolerable burden. In 1963, William Zantzinger, shitfaced drunk at the bar of Baltimore’s Hotel Emerson, began cursing the bartender and striking her with the toy cane he was carrying and abusing her in the vilest, most racially charged language, Hattie Carroll continued to fix him the bourbon and ice he was shouting for even as the stroke that would kill her was coming on.

Ultimately, for a man like Henson, Dabney or Francis to express any aspiration beyond a desire to continue mixing excellent drinks for the local Rotarians was to step out on very thin ice indeed. As Dabney told his son, “Never … let a white man know how much you really do know about anything except hard work.” And yet, while their way was beset with higher and more dangerous obstacles than the paths their white fellow bartenders faced, the latter faced a path that was far from smooth. In fact, many of these black bartenders prospered to a degree that was highly unusual for the profession, black or white.

To win acclaim for mixing drinks in the 19th century meant mastering an intricate craft that took years of apprenticeship (there were essentially no schools and the available books were rudimentary at best). Bartending involved brutal hours, occasional physical danger (even in the best saloons, patrons would sometimes set to playing with guns and knives) and constant physical labor. To prosper at it required intelligence, dexterity, temperance and, when it came to dealing with customers, a broad general knowledge and a considerable portion of wisdom. And yet even its most skilled practitioners won little respect from society at large.

A successful bartender would find himself celebrated, it’s true, but only by a narrow sector of society. Saloons tended to be populated by a raffish crowd of dissipated clerks, ward-heelers, police-court lawyers, avant la lettre trustafarians, newspaperman, hand-shakers, drink-cadgers, gamblers, pimps, confidence men, stock-jobbers and suchlike and avoided by the conscientious and the respectable. Jerry Thomas, the greatest barkeeper of the age, died in poverty, as did William Schmidt, the second greatest. Although both were lionized by the sporting press, the more serious newspapers treated them with amused condescension. (Two examples: Alan Dale, Hearst’s drama critic, described Thomas as a “greasy little man,” while Julian Street, who encountered Schmidt as a cub reporter, recalled him as “a short, roundheaded man with an amiable eye and an immense mustache” and thought that the shape of his head meant that his erudite 1892 drink compendium, “The Flowing Bowl,” was probably ghost-written.)

This brings us back to Louis Deal and George Bear and the question of why black bartenders were tolerated and even embraced in the South and utterly rejected in the North. When Beck finally let Deal go, the Cincinnati Enquirer made sure to track down Bear and elicit his reasons for the vehement opposition to Deal. Bear claimed he wasn’t a racist, of course — indeed, he had “no objection to the colored man as a helper or porter, as was the case in many saloons.” The problem, he explained, was that “too many good white men were in need of situations to permit of the introduction of colored barkeepers in first-class establishments,” adding that it wasn’t “a matter of personal spite, but of self-protection.”

Off the record, however, the white bartenders said something different: Deal’s employment, they claimed, was an intolerable “insult to the white men engaged in the same business.” Here was the crux of the matter. It wasn’t just that black men would be taking open jobs, it was that they would be redefining the very status of the job. In the last decades of the 19th century, bartenders strove to extract their profession — under strong attack from a powerful temperance movement that regarded them as, essentially, accessories to slow murder — from the louche sporting milieu in which it had evolved and turn it into a regular profession. They unionized, started wearing uniforms (Jerry Thomas’s brocade vests and diamond stickpins were out, replaced by the neat white coat), established schools and subjected themselves to the frugal discipline of the cash register. Rather than tossing drinks from glass to glass in a wide liquid arc or shaking them, they preferred to stir them, with an elegant, restrained rotation of the wrist; much less vulgar. Elaborate garnishes were reined in, drinks got lighter and dryer and less intoxicating. Bartending, the suggestion was, was skilled labor, just like, say, making watches or taking photographs. A bartender was a solid member of the middle class. A bartender was respectable.

To the average white American in the late nineteenth century, black labor was essentially synonymous with unskilled labor. To a degree, that was not wrong (and here I am drawing mostly on R. R. Wright’s 1913 article in the Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, “The Negro in Unskilled Labor”): The 1900 census showed 75 percent of black workers performing such labor, and a large proportion of the remainder doing their skilled labor in an agricultural context, where a townsman such as George Bear would not see them. Only 6.9 percent of black workers were found in the (skilled) “manufacturing and mechanical pursuits” and 1.2 percent in “professional service.” This wasn’t the whole story: In fact, the percentage of skilled black workers was — despite every obstacle thrown in their way — rising rapidly. But as Wright observed, although the black unskilled worker was a “welcome guest” in Northern cities and was migrating there in large numbers, it was only with “extreme difficulty” that the skilled black worker found a place there.

From the point of view of George Bear and his fellow barkeepers in “first-class establishments,” to tolerate black men behind the bar in such a place was as good as to acknowledge that bartending wasn’t watchmaking; that it wasn’t skilled labor. It didn’t matter the slightest that a man like Louis Deal could stir up a perfect Widow’s Kiss and had a sure-fire hangover cure. For Deal and his fellow black mixologists, of course, this was a perfect Catch-22: the very act of stepping into a lucrative job in a first-class saloon destroyed the value of that job.

The South clearly saw these issues differently. As to why it did, I don’t have a facile answer, and I suspect one that isn’t facile would take a dissertation’s worth of research and analysis. But the social system in the South made a place for certain skilled black individuals to prosper and did not regard them as unusual. Those men paid for that place, more than we can know, but they had it. And that alone is remarkable. It’s always difficult to keep the moving parts of a complex system working smoothly and consistently together. That’s particularly true if the system in question is a mental one. All such constructs are subject to drift; it doesn’t help that we can rarely even see all the parts, all of the ideas from which the system is built, since many of them are hidden even from ourselves. As a result, things get out of whack. Contradictory notions are clung to unaddressed and unresolved. The South went to war to defend the principle that black people are inherently inferior to white people (or, if you prefer, to defend its right to apply that principle; it amounts to the same thing). Yet, as his son observed, at the same time John Dabney’s “reputation and business standing rendered him almost immune to segregation, ostracism or racial prejudice.” Indeed, in 1866 the Richmond Enquirer said about him that “those who know him best place the most implicit confidence in his honor.” That confidence — invested in something that, according to the expressed principles of the society in which he was raised, he could not have — was earned one elaborate Mint Julep at a time.

I like to think that there’s something about a great drink from a great bartender that kindles the flame of geniality and distills an extraordinary benevolence in whoever partakes, and that the careers of these extraordinary men are proof of that. But then again, I would.