“Not again.”

That was the text my dad sent me after Jermaine Kearse, the Seahawks receiver, bobbled the ball over his entire body like a contact juggler before holding onto it inside the Patriots’ 10-yard line. My stomach pitched and lurched. I sank down into the couch like loose change.

“Hey, this might sound weird,” I said to the entire Super Bowl party around me, “but however this game ends, I think I’m going to start crying. My grandmother died. I’ll explain after.”

It was embarrassing to admit to a room full of cosmopolitan New York writers and media professionals (in other words, non-townies) who felt more vicarious embarrassment for Katy Perry’s rhythmless Left Shark than attachment to any football team. Nobody expected to be in the presence of an actual Sports Maniac, the kind of person whose happiness depends on the score of a game played thousands of miles away. Until last fall, I didn’t even know if I was one of those people.

And then Nana Kay, my last surviving grandparent, got sick. Well, she’d been sick, but in October we found out what it was. The pain in her legs, which had grown unbearable around her 89th birthday, wasn’t arthritis; it was lymphoma. Suddenly, she needed 24-hour care from her three children, which my father and his siblings dutifully provided in shifts, even after she was admitted to Newton-Wellesley Hospital outside Boston.

Although my grandmother was a strict parent and abided my grandfather's kosher diet, as a Nana she had grown away from religion and was almost unbelievably permissive. She participated in my bar mitzvah, proudly but with no sense of comfort or familiarity around the Torah. On the other hand, a few years ago, I’d given her a recording of a stand-up comedy show I’d done.

“There’s some adult material on here, and if you have any questions about what it means...never talk to me about it,” I said.

A week later I got a one-sentence email (a feat in itself) from her: “Oh I get it.”

She’d been so healthy up until her diagnosis that the doctors spoke of her condition in terms of “full recovery” rather than “years/months/days left.” Still, the time in the hospital wore on her. She was used to being independent; she’d been retired less than a decade, working into her eighties doing patient billing for hospitals to finance trips to all seven continents.

When you’re confined to a hospital bed, there aren’t many appointments you can make. You await visits from friends and family members. You enjoy the coconut ice cream they smuggle in. You tolerate the erratic and invasive visits of doctors and nurses, hoping that one of them will bring you closer to going home. But you don’t have a lot of control over your social calendar. During my grandmother’s hospital stay, the NFL schedule became the one event she could make an appointment for herself. Physical therapy and visits from cousins came according to the whims of everyone around her. Patriots games were her time.

“I wish I’d been able to stay up and watch the second half,” she told me with a sigh over the phone the morning after one game, the frustration with her illness boiled down to a single point of practical concern.

Before Nana Kay was diagnosed with cancer, I thought I was done with the NFL entirely. I had walked away, and I had no regrets. It was disappointing because I had a long history as a fan. In 1986, my dad squeezed infant-me into a “squish the fish” T-shirt for good luck...right before the Patriots got crushed by the Bears. I’d celebrated the team’s three Super Bowl wins and agonized over the three losses in the big game. Where I’m from, this qualifies as “casually following” a team. I wouldn’t call myself a “bro,” but I would say I’m a “hardened twerp.” Plus, kickoff always reminded me to at least text my dad. But, between the league’s dismal handling of domestic violence issues to their resistance to effectively addressing the brain injuries sustained by their players, I couldn’t watch a game with a clear conscience. Also, the Patriots looked bad. Like, really bad. Smoked 41-14 in late September by the lowly Kansas City Chiefs on Monday Night Football bad. But in spite of all that, my grandmother had latched onto the team this season.

Honestly, I had never really thought of my grandmother as a sports fan; the rest of her personality was too vibrant and far-ranging to be defined that way. Kay Gondelman was adventurous and candid and sarcastic and generous. She always brought family members a souvenir from her latest trip to Asia, but she never hesitated to tell someone how the birthday gift they got her had missed the mark. During the summer of 2011, as I was preparing to move from Boston to New York, I took my grandmother out to lunch. Afterward we went back to her apartment where she had baked a cake for dessert. We sat at her dining room table and talked about everything you’re not supposed to talk about with a grandparent. Abortion, religion, even (gasp) Israel. She told me, for the first time, how she hadn’t believed in God for decades. She couldn’t believe that a benevolent force would allow the horrors of the world (I don’t need to list them here) to persist.

It was comforting to hear her thoughts because I’ve never felt attached to Judaism in any traditional way. I’m not religious. But I’m also not spiritual. I used to drive home from New York to Boston for the Yom Kippur and Passover at my mother’s request, but over the years, my motivation to make those trips has dwindled. At this point, the most Jewish thing about me is that I really love the Beastie Boys. I appreciate how central religion is in the lives other people, but it has never resonated with me. I imagine this is how lots of people feel about things I love, like rap music or, it turns out, sports.

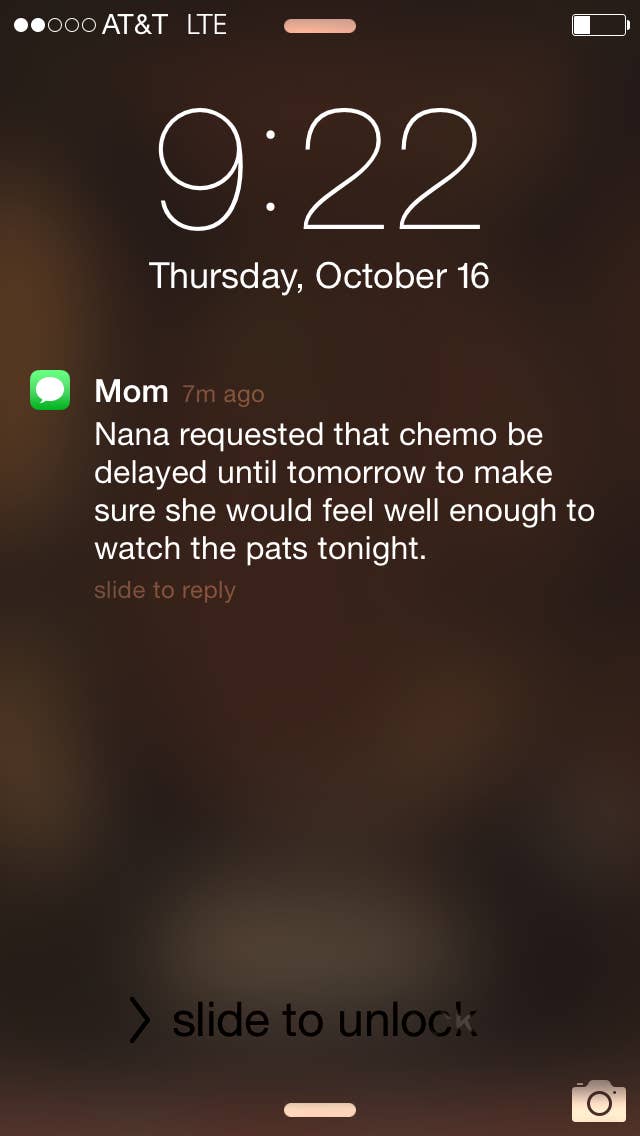

I didn’t quite realize how central the Patriots were to Kay’s life until I got a text from my mother near the end of October saying she’d delayed a cancer treatment to guarantee she’d feel well enough to watch the Pats play. That is, in my estimation, the strongest possible commitment to a sports team. Forget waking up at 5:30 to tailgate or even getting a mascot tattooed on your ankle. There is no more impressive show of team spirit than postponing chemotherapy to watch a game.

She started chemo the next day, but it didn’t take. The doctors were able to manage the pain, but there were complications, and those complications interrupted the chemo, and the cancer spread. But the NFL season continued, unhindered. By this time, whatever moral high ground I’d taken against the NFL had eroded. While my job in New York kept me physically distant from my grandmother most of the time, keeping track of football gave us something to talk about on the phone. Watching ESPN highlight packages gave me the comfort I imagine people derive from murmuring a prayer over rosary beads.

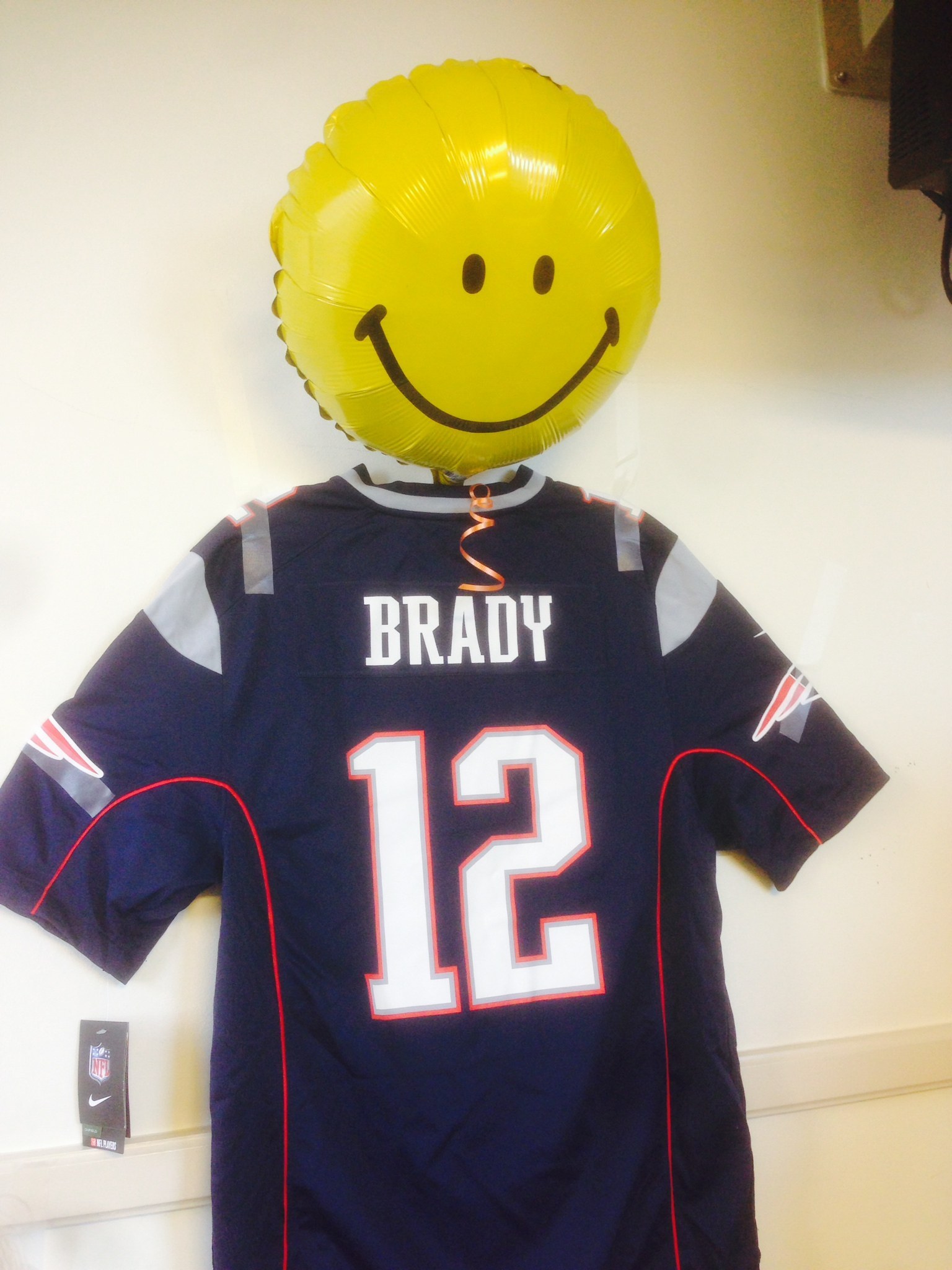

When I visited in November, I brought a Tom Brady jersey. My father duct-taped it to the wall of the hospital room. I told her about my plans for the time off over the holidays.

“I’m going to finish writing my book.”

“Yeah, I’ve heard you say that a lot,” she replied.

By the time I came home for Thanksgiving, the doctors had given up on the chemo and sent my grandmother home. My family ate Thanksgiving dinner at her house like we always did, but she wasn’t well enough to leave her bedroom. I sat with her before returning to New York.

“I love you,” I said.

“I love you,” she whispered. I squeezed her hand and walked toward the door.

“Don’t party too hard!” I called to her, over my shoulder.

She died the following Monday. My mom called to tell me, and I stoically made plans to return for the funeral. An hour later, I got a text saying that my grandmother was going to be cremated with the Tom Brady jersey. Then I cried, thinking that if she hadn’t just died, my grandmother could be elected mayor of Boston on that platform alone. I later joked to my parents that I couldn’t control my tears because I’d paid like a hundred dollars for that shirt. I think she would have appreciated it.

So two months later, when the Seahawks seemed poised to clinch an improbable Super Bowl victory, everything felt so unfair. Don’t you accrue some kind of sports karma when you are laid to rest, ashes intermingled with officially licensed team apparel? And then, when Malcolm Butler jumped a route and intercepted Russell Wilson’s pass over the middle, reclaiming the game for the Patriots, I was overwhelmed by how unfair everything still felt. My grandmother, who showed unbelievable devotion to her team, missed its most thrilling moment.

Even in my excitement over the result of the Super Bowl, I didn’t feel like my grandmother was present or watching over me. I felt her absence in an acute, urgent, painful way. Because she wasn’t present. She was dead, and she missed out on something that would have brought her a lot of joy. Tears leaked down my face on the long subway ride home. I realized I may never be able to watch football again without missing her. I realized that might be a good thing. Despite its flaws, the NFL has given me a wonderful gift of remembrance, which is how I imagine a lot of people feel about religion.