This is a guest post by Angela Harrison Eng

Winter storms like hurricanes are regularly named every year. This naming practice, however, was not always the norm. One snowstorm that hit DC in 1922 was named “The Knickerbocker Storm” (see photos of the blizzard) because it indirectly led to the deaths of 98 people inside the historic Knickerbocker Theater.

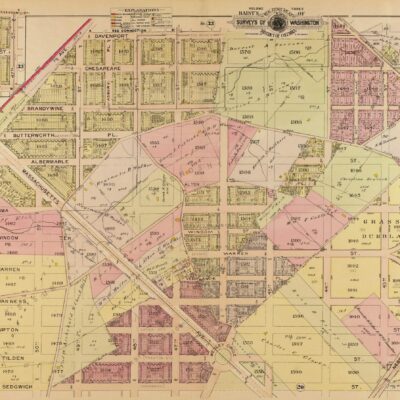

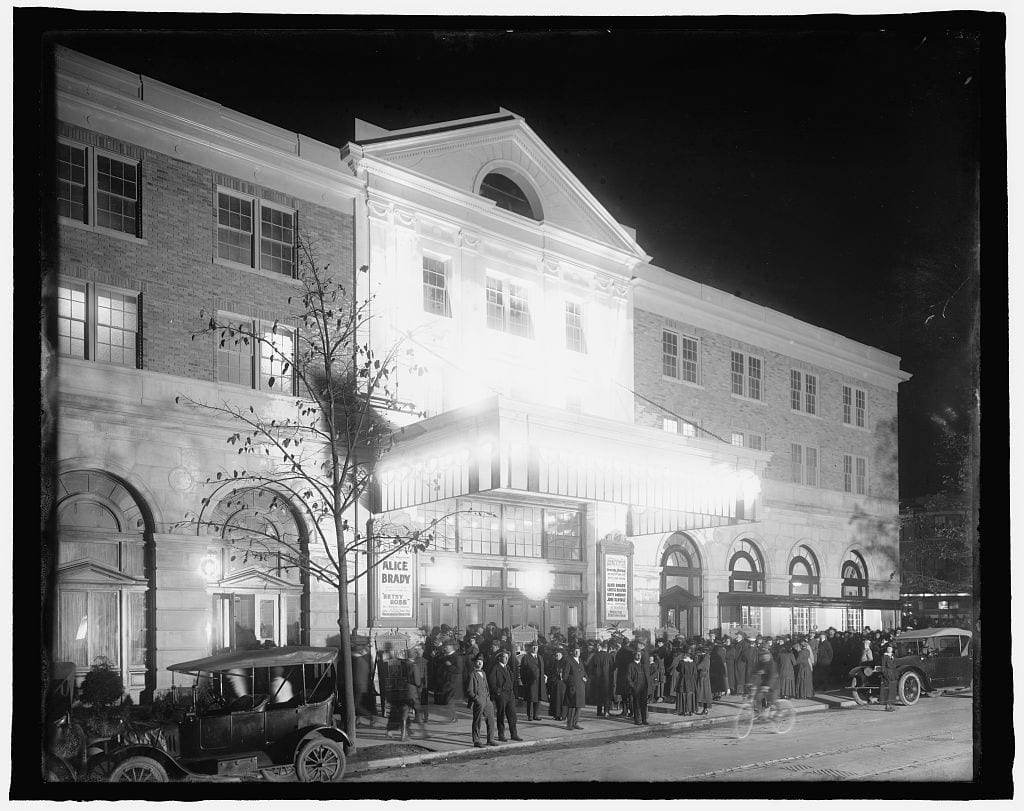

The Knickerbocker opened on October 13, 1917. The theater was built by movie-house mogul Harry Crandall and designed by architect Reginald Geare. It was located at 18th Street and Columbia Road, which is now in the Adams Morgan neighborhood.

An earlier article from the Post dated October 7, 1917 detailed the opulence and grandeur of the new theatre: “The structure, wholly unlike anything of the kind yet built in Washington, is absolutely fireproof throughout and the walls are of Indiana limestone and Pompeian art brick. The auditorium is in the shape of an elongated triangle.” The stage was at the peak of the triangle, and the theater featured a sloping floor so there were no obstructed views. It seated 1,800 people. The theatre also boasted reserved boxes, a mezzanine, and a Japanese tearoom on the second floor. The interior color scheme consisted of ivory, gold, and pale blue. It also had a ventilation system, which author John DeFerrari points out was quite the advanced feature for a movie house at that time.

The theater opened to much fanfare. A Washington Post article detailed the event, which included a buffet dinner and introductions of the movie stars in attendance. Betsy Ross was the first film shown and the star of the film, Alice Brady, was present at the screening. For the next few years, the theater experienced much prosperity. A number of fundraisers and lectures were held, and movie schedules ran on a regular basis in the Post.

The Knickerbocker remained successful until a terrible snowstorm hit in late January 1922. Kevin Ambrose, moderator of the Weatherbook site, writes that the snowstorm was—and still is—the worst snowstorm in DC history. It began late on January 27th and continued through January 29th, covering the District with a record 28 inches of snow. The Knickerbocker nevertheless remained open the night of the 28th, showing a comedy film entitled Get-Rich Quick Wallingford. The Post noted that it was standing room only that night, and the theater was packed. Shortly after the second show of the night was starting, the roof of the theater caved in under the crushing weight of the snow.

A Post article from the day after the disaster recounts the horrifying moment:

“A man who had just entered the theater and barely escaped with his life, said that a hearty peal of laughter preceded the falling in of the roof. ‘Great God!’ he exclaimed, ‘it was the most heart rending thing I ever want to witness.’”

More haunting stories emerged from the article. Two young boys survived by hiding under their seats when they heard the roof crack just prior to its collapse. A man escaped the rubble only to lose his brother and sister-in-law seated next to him. Priests gave absolution to those dying or dead underneath the wreckage.

A makeshift triage was set up in a nearby candy store with doctors and nurses sent to the scene carrying supplies from Walter Reed. An article from The Atlanta Constitution printed the day after the disaster noted that some emergency hospitals were even set up in the nearby neighborhoods, including the homes of government officials. Footage exists of the aftermath, showing the general chaos that ensued afterwards. The initial death toll was 22 according to the Post, but the number would rise in the following days.

More details about the tragedy were published in the Post on the 30th. The article described the scene as a war zone, comparing it to the “havoc in France or Belgium or England” during the First World War. The roof was completely gone, “as if a giant’s knife had just cut the top off and left no vestige of it,” while the twisted mess of concrete, steel, wood, and snow lay in a “death pit” in the middle. The author described the loss of life as “two layers of death, as in a cake.” Those two layers were the people the roof fell directly upon in the middle of the theater and those under the collapsed balcony.

The article’s author also recounted the cries of the wounded or dying, noting that the only way rescuers could identify where people were buried was from their screams. Another Post article from January 30th puts the death toll at 107, with stories of rescuers working nonstop throughout the night to save who they could. One man named Scott Montgomery reportedly survived 12 hours underneath the wreckage, though “his legs were almost severed from his body by a steel girder.” He apparently begged for the rescuers to help his date, Veronica Murphy, all the while insisting he was fine. Veronica, however, had already died and her arm was around him the entire time. He passed away soon afterwards. An article from The Bridgeport Telegram tells the story of a 5-year-old girl who survived the cave-in because the 2 ladies she sat between shielded her body with their own. Neither woman survived.

The final death toll was 98. An inquiry was launched soon after the incident in order to determine why the roof collapsed. Many suits were filed afterwards. The inquiry found, according to the Lost Washington blog, that “the contractor had inserted the steel beams supporting the roof only 2 inches into the walls rather than the 8 inches Geare had specified.” As a result, both Crandall and Geare were cleared of any charges. However, neither man lived happily ever after.

The Post article mentioned that Geare was arrested for drunk driving in January 1926. He committed suicide the next year. As for the theatre, DeFerrari noted that the shell was used for the Ambassador Theater, built in 1923. Crandall continued to run his theaters, but they declined in popularity with the rise of big studios such as Warner Brothers. He sold what he had left and ultimately committed suicide in 1937.

The Ambassador has an interesting side story. As the independent movie theater declined in popularity, three young men decided to rent out the now-gutted theater and turn it into a concert hall. They named it The Psychedelic Power and Light Company. The blog DC Rocks recounted the first failed attempt to get The Grateful Dead to play, but eventually acts such as Canned Heat, John Lee Hooker, Vanilla Fudge, and more came through. The biggest act, without a doubt, was a young Jimi Hendrix, who played a 5-night stretch.

The Ambassador stayed open about another year, and then shut down for good. A small site dedicated to the memory of the theater contains a collection of various ephemera such as posters, photos, ticket stubs, and other documents.

It was torn down in 1969 and replaced with a bank. It is now a SunTrust Bank with a small plaza in front.

Here is the Google Street View of the location today. Also, check out film footage of the aftermath.