A young Irish student was one of the first people from outside Germany to recognise the danger of Adolf Hitler’s inflammatory oratory, a new biography reveals.

Daniel Binchy, who went on to become the Irish ambassador to Berlin between 1929 and 1932, spotted Hitler’s rhetorical power inside a Munich beer hall in 1921, when the future Nazi dictator was nothing more than the leader of a small “freak party”.

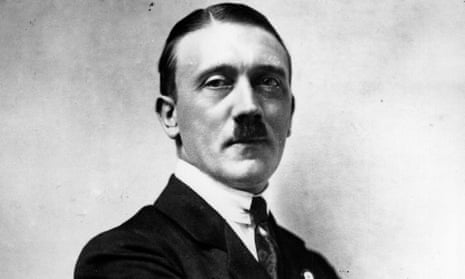

Writing in his diary about a trip in November 1921 to Munich’s Bürgerbräukeller, Binchy describes seeing a man with a “carefully docked ‘toothbrush’ moustache” giving off an “impression of insignificance”.

Hitler, a virtual unknown, rises to speak, at which point Binchy is struck by his transformation: “Here was a born natural orator. He began slowly, almost hesitatingly, stumbling over the construction of his sentences, correcting his dialect pronunciation. Then all at once he seemed to take fire. His voice rose victorious over falterings, his eyes blazed with conviction, his whole body became an instrument of rude eloquence.

“As his exaltation increased, his voice rose almost to a scream, his gesticulation became a pantomime, and I noticed traces of foam at the corners of his mouth.

“He spoke so quickly and in such a pronounced dialect that I had great difficulty in following him, but the same phrases kept recurring all through his address like motifs in a symphony: the Marxist traitors, the criminals who caused the revolution, the German army which was stabbed in the back, and – most insistent of all – the Jews.”

Hitler stayed in control of most of the audience, Binchy recalls, despite some heckles.

“His purple passages were greeted with roars of applause, and when finally he sank back exhausted into his chair, there was a scene of hysterical enthusiasm which baffles description. As we left the meeting my friend asked me what I thought of this new party leader. With all the arrogance of 21 I replied: ‘A harmless lunatic with the gift of oratory.’ I can still hear his retort: ‘No lunatic with the gift of oratory is harmless.’”

Binchy had a second encounter with Hitler in Berlin in 1930, when the Nazis were on the brink of power.

“In his speech I found no change at all. Allowing for the altered place and circumstances, it was substantially the same address which I had heard in the Bürgerbräukeller. There were the same denunciations, the same digressions – and the same enthusiasm. At the conclusion of his speech the vast throng cheered itself hoarse. The obscure housepainter was now the leader of the second largest party in Germany.”

Binchy’s warnings about Hitler in 1921 and 1930 are contained in The Lives of Daniel Binchy: Irish Scholar, Diplomat, Public Intellectual, a new biography by the Irish academic Prof Tom Garvin.

It includes an article Binchy wrote in 1933 in the influential journal Studies, again warning about the danger posed by Hitler and totalitarianism.

The diplomat and intellectual, who later held senior positions at University College Dublin, Corpus Christi College, Oxford, and Harvard, was the uncle of the bestselling Irish novelist Maeve Binchy.