Most runners get into the Boston Marathon in one of two ways: Meet strict qualifying standards or raise thousands of dollars for charity.

But some choose a third option. They cheat.

That’s what a firefighter in his 50s did last year. He cut the course at his qualifying race, a marathon in 2013, submitted a time he knew was false, and took a spot at the starting line in Hopkinton in 2015.

“This is absolutely deflating,” he said after Runner’s World presented evidence of his course-cutting. “My life and my job are based on integrity. And I cheated.”

The firefighter is one of at least 47 runners who skirted the rules last year to gain entry into the most prestigious marathon in the country, according to an investigation by race-results watchdogs. The investigation is ongoing.

With its 119-year history and tough qualifying standards, the Boston Marathon has become one of America’s most prized race experiences, and gaining entry is more difficult every year.

These days, it’s not as simple as running the qualifying time for your gender and age group. Registration for Boston opens every September on a rolling basis, and the fastest people get spots first. The race fills before everyone with a qualifying time can register.

In the past two years, you’ve had to be a good bit faster than your qualifier in order to gain entry to Boston. But exactly how much is a moving target.

For the 2015 race, athletes had to run at least 1:02 faster than their qualifying time to earn a bib, leaving out 1,947 runners who met the posted standards. It got more selective for the 2016 race. Successful entrants had to be at least 2:28 faster than their time standards, and4,562 runners were not accepted.

Those who aren’t fast enough to qualify can run with one of Boston’s 27 partner charities, but they have to meet fundraising minimums of $5,000.

Facing these challenging standards, some skirt the rules to snag a coveted bib.

The most common ways:

- obtaining the bib number of someone else who legitimately qualified, a practice referred to as bib swapping

- allowing a faster runner, known as a “bib mule,” to carry their number at a qualifying race

- cutting the course at a qualifying race to achieve the required time

- falsifying race results.

Tom Grilk, the executive director of the Boston Athletic Association, said the marathon goes to great lengths to ensure the integrity of the race’s registration.

“We take this stuff seriously and take measures to address it,” he said.

He also said the number of suspected runners who obtain a bib without qualifying represents an “infinitesimal percentage” of the 32,000-person field.

But recent high-profile cases of suspected cheating and Boston disqualifications have fascinated the running community. So much that internet sleuths belonging to a private Facebook group called “Race Cheat Investigation” embarked on an exhaustive effort to answer a simple question: How many ran Boston last year who shouldn’t have?

An Investigation Begins

The current scrutiny toward how people qualify for the Boston Marathon is largely thanks to one man: Mike Rossi.

The Pennsylvania dad drew national attention last May after penning a letter on Facebook. In it, he criticized a school principal who said his kids’ trip to Boston with him for the marathon would not be considered an excused absence. Multiple media outlets picked up his story.

Runners, meanwhile, quickly raised questions about how Rossi entered Boston. They noted that his qualifying time at the Via Marathon in Allentown, Pennsylvania, was inconsistent with his other available results and that he didn’t appear in race photos along the course. (Rossi has denied wrongdoing.)

The case spawned a 22,000-post forum on the website LetsRun.com—and drew the attention of Derek Murphy, a 45-year-old business analyst in Cincinnati.

Murphy started a blog about race cheating, and last summer with three colleagues began pursuing their ambitious project to figure out how many people got into Boston by breaking race rules. Their first step was to cull the entire list of finishers into a smaller group of likely suspects.

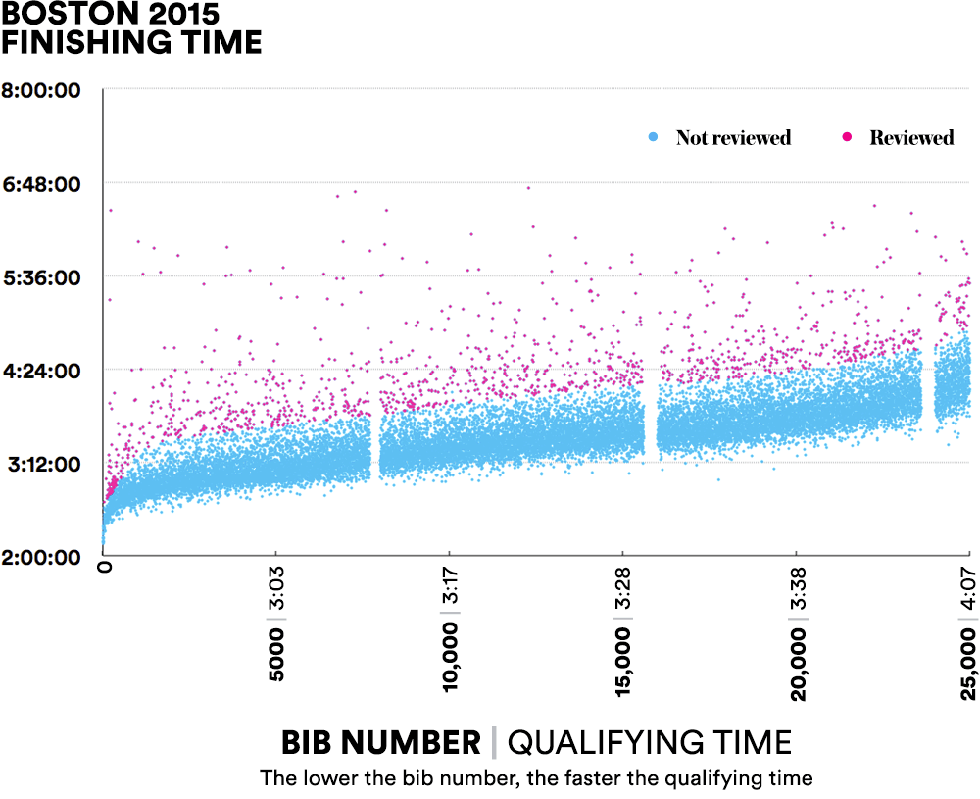

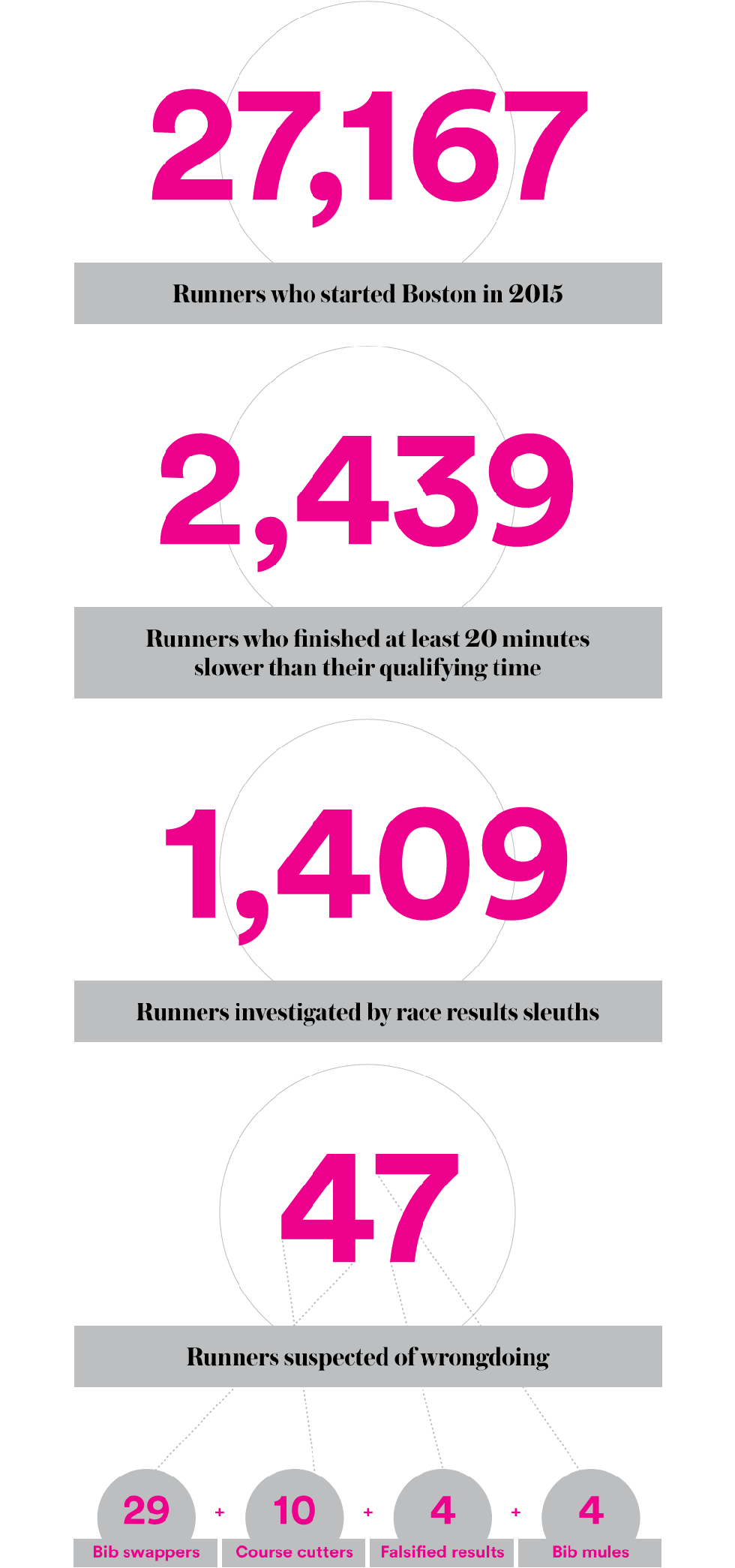

Bib numbers at the Boston Marathon indicate runners’ qualifying times: Lower numbers mean faster runners. Murphy developed an algorithm to pinpoint all finishers who ran Boston at least 20 minutes slower than their qualifying time. The search yielded 2,439 names.

Spotting the Suspects

Of course, runners could have been slowed for a variety of reasons. A nagging injury, perhaps. Or the rainy and windy conditions at Boston 2015. Or they were running with slower friends.

Or, as Murphy hypothesized, the disparity in time could mean that the runner was not capable of achieving the time indicated by his or her bib number and had entered the race without the proper credentials.

Murphy and his team then began methodically examining available information about each of those runners. First they searched Boston Marathon results to confirm the runner’s time in 2015, and to see if he or she had run the race in previous years. They then looked at MarathonFoto.com to view the runner’s photos from the race. From there, they scouted race-results aggregation websites like Athlinks and MarathonGuide.com. Those led them to more races and more photos.

The team found, for example, a high school educator who submitted a sub-3:20 qualifying time to Boston. Athlinks showed her next-fastest marathon to be more than 50 minutes slower. Murphy found photos indicating a man had run under her name at the 2013 New York City Marathon to achieve the qualifying time—a textbook example of a bib mule.

By the end of March, investigators had gone through 1,409 of the 2,439 people, and found from those the 47 cases of questionable qualifiers. They expect to find more as they continue digging.

After seven months, Murphy is deft at spotting suspicious results. When his wife and two children are asleep, he turns on ESPN, settles into his recliner, and opens his laptop. On the screen, he scans a spreadsheet with the data of the participants his algorithm flagged.

“This is the rare time that I get to myself,” Murphy said. “This is when I unwind.”

While Murphy is a runner, he said he will never qualify for Boston and prefers the long, slow march of an ultramarathon. He is currently training for his third 24-hour race.

He loves the analytical challenge of catching those who have questionable methods of entering Boston. And he’s curious about them.

“I always wonder why someone would do this,” he said. “I know how hard it is to get faster. And then I see people who take shortcuts or are dishonest.”

The Qualifiers With Question Marks

The 47 runners Murphy identified by the end of March come from France, Italy, Japan, Australia, Canada, and the U.S. Most are in their 30s and 40s, and 33 are male. They work in business, civil service, education, and government. Two publish running blogs.

According to Murphy, 29 received bibs from legitimate qualifiers, 10 are suspected of cutting the course at their qualifying race, four used bib mules, and four appear on race results that were falsified.

Runner’s World has decided not to release their names, although a reporter has reviewed each case. Murphy plans to pass the results of his investigation to the BAA.

One of the runners identified by Murphy was the firefighter who cut the course at his qualifying race. Over two telephone conversations, he explained why he did so. Runner’s World agreed not to name him.

He said he’d been close to qualifying at two previous marathons, but injuries slowed him. His sister, also a runner and a Boston Marathon qualifier, hoped one day they could finish the iconic race together.

In November 2013, the firefighter planned on qualifying at a certified marathon. By mile 16, he knew he was off pace. He came to a section of the course that turned right for a two-mile out-and-back leg. Across the intersection, in front of runners returning from the section, he eyed a port-a-potty and ducked inside.

“When I came out I saw guys going right and thought, ‘I could do two more miles, or I could roll the dice,’” he said. “So that’s what I did.”

The marathon had four mats capturing timing information from chips on every runner’s bib. The race’s results show that the firefighter crossed all four of those mats. He averaged 9:18 per mile for the first half marathon. But between mile 13.1 and mile 20, the results show he ran 4:12 per mile pace, impossible splits.

Even his public Runkeeper profile, which included GPS information about the qualifying marathon, showed exactly where he cut the course. It said he ran 22.3 miles. (The account has since been deleted.)

The anomaly caught Murphy’s attention.

On Facebook, after cutting the course, the firefighter wrote, “I just qualified for the Boston Marathon two days ago! So will be doing that in 2015!”

Nearly two and a half years after that post, and almost a year after running Boston, he expressed regret for the decision.

“My teeth are grinding, I am so sick to my stomach,” he said. “If I could take this back I would.”

He suspects three or four people know that he cut the course, including his sister. One of his coworkers confronted him after the 2013 race, but they have not discussed it since. “It’s what firemen do with bad calls and bad situations; they don’t talk about it.”

His wife, also a runner, does not know. He said he plans on telling her. But he fears if his name gets out, he will have to retire from his job early. “I have a reputation,” he said. “This is very bad.”

The Investigation: By the Numbers

In another case, Murphy started to investigate Gia Alvarez, a popular blogger, after a tipster emailed saying Alvarez gave her 2015 Boston Marathon bib to another runner. Alvarez used the time the other runner ran at Boston in 2015 to register for this year’s race. The BAA has since disqualified Alvarez—and banned her from future events.

“I really am sorry,” Alvarez told Runner’s World. “I am not trying to make excuses for what I did.” She said she became pregnant between registering for Boston 2015 and the actual race.

“So I stupidly gave my number to a friend. I genuinely did not know what time she was going to run,” Alvarez said. “When she ran a qualifying time, I was surprised. Then I made a bad decision.”

In a blog post Alvarez wrote about her disqualification, she acknowledged that she gave her number away in 2015, but she didn’t write about how she used that runner’s time to get her a spot in this year’s race. After an outcry on running message boards, Alvarez wrote a second post, apologizing for that transgression.

Other runners who were contacted for this story did not respond to interview requests, declined to comment, or denied wrongdoing.

How Bibs Change Hands

Even after cases of suspected dishonesty in qualifying have drawn national attention, runners continue to request bibs they didn’t earn, or ask someone to run a qualifying race for them.

The solicitations crop up in conversation during long runs, in private Facebook groups, or on anonymous forums.

Brian Benestad, a lawyer from Pittsburgh and 2:36 marathoner, said in 2013 he was asked by two different runners to carry a bib at a qualifying race.

Related: Is It Ever Okay to Race With Someone Else’s Bib Number?

A race director for a large, IAAF-certified marathon in Europe told Runner’s World four different runners over the past 10 years have offered to pay him to change their results.

“I would be devastated and flabbergasted if any race director actually did it,” said the organizer, who declined the offers. “You would be cheating every honest athlete. I feel very sorry for the people that asked me.”

Last September Clare Duffy, a 50-year-old New Yorker, qualified for her first Boston with a 3:47 at the Last Chance BQ2 Marathon. She was heartbroken when she sustained a stress fracture in her foot, which will keep her from the starting line next week.

And she was appalled when an acquaintance asked her over Twitter on April 5 if she would go to the Boston expo and pick up her number to give to another runner. Duffy refused.

“I would never have considered it, based on the fact that Boston is sacred,” Duffy said. “Not just because if I ever got caught I would be banned.”

In early February, an anonymous runner who calls himself “J” posted to a forum on MarathonGuide.com asking for a bib.

“Need someone to take your Boston number and qualify you for next year? Have a Charity number and can’t run due to injury? I will run whatever time you need to qualify for next year,” he wrote.

Over the phone, J is surprisingly candid. He said he’s run the Boston Marathon four times, twice as a legitimate qualifier and twice with someone else’s bib. Runner’s World agreed not to name him.

Although his advertisement suggests otherwise, he claims to use bibs only from people who already qualified but could not compete because of injury or unexpected conflict.

“I am not going to apologize for running in the place of somebody who would have been there anyway,” he said. Before the race, he requests the expected finishing time from the runner. He then matches their time so they can register next year. He claims he can run a 2:50 marathon, which would qualify anyone for the race.

J said he will not run a qualifying time for someone who is not capable of doing it—but eight of the 12 responses he has gotten from his ad have asked him to consider doing so.

He’s already secured a bib for Monday’s race and is making plans to meet the registered runner at an undisclosed location in Boston before the race to pick up the bib.

“I can’t wait,” he said.

Heightened Vigilance

While no specific Massachusetts law addresses race registration fraud, attorneys say the BAA would have grounds to pursue legal action against those who misrepresent their qualifying times or identities.

“It’s like letting someone take the law school exam for you, then using that score to go to Harvard,” said Les Smith, a lawyer and an event director for the Portland Marathon. He believes the BAA would likely win a civil case if the organization ever chose to act.

“The person using another person’s bib is guilty of false impersonation and fraud with intent,” Smith said, adding that the person giving away a bib is also responsible. “If Boston took on such a cheater, it would send ripples through the industry and clean up this pervasive practice.”

Related: Do Boston’s Qualifiers Look Down on Charity Runners?

For his part, Tom Grilk at the BAA is satisfied with the registration process. “We look to race directors to stand behind their results, and they do,” he said.

Murphy said the investigation is not an indictment against the BAA. He recognizes that the number of suspected cheaters is a tiny portion of the field. More than anything, he hopes his work will act as a deterrent.

He wants people to know that a self-described math geek in the Ohio suburbs has the time and patience to comb thousands of race results to root out suspected cheats. He already plans to conduct another investigation after Monday’s race.

The firefighter who cut a course to qualify for the 2015 Boston Marathon had no idea someone would be willing to dig deep enough in the results to catch him. He also said he had no idea he took away a bib from a legitimate qualifier.

Over the phone, he sighed: “Knowing that, I feel pretty frickin’ bad.”

Sarah Lorge Butler and Kelley Stump contributed to this report.

Kit has been a health, fitness, and running journalist for the past five years. His work has taken him across the country, from Hayward Field in Eugene, Oregon, to cover the 2016 Olympic Trials to the top of Mt. Katahdin in Maine to cover Scott Jurek’s record-breaking Appalachian Trail thru-hike in 2015.