Sean Thomas’s first published books were unsuccessful. They were literary, mostly, exploring themes of masculinity in the modern world, and they did not sell well. As middle age crept up without financial security, his agent began nudging him towards Da Vinci Code-inspired thrillers. He couldn’t see putting his real name on them. “My own name was associated with freelance journalism about art, sex and politics, and had the taint of literary failure. Also, it just wasn’t butch enough”, says Thomas. Tom Knox, his new alter-ego, was born, and sales soared.

“Tom Knox was the flimsiest of masks,” says Thomas. “And yet, as I wrote the first book, The Genesis Secret, he developed in my mind: a younger, better looking version of myself. I imagined him jogging on a Malibu beach with his pure-bred borzoi dogs.

“It was a joke, of course, and yet he did become a second personality. It was liberating, and allowed me to play with tropes and characters that I wouldn’t have addressed when I was ‘serious’ novelist Sean Thomas,” he adds.

But then the demand for religious conspiracy thrillers dwindled, and Thomas moved on to a taut, more “upmarket”, domestic psycho-thriller.

“The switch was abrupt,” he says. “From Grail-hunting drug cults to wistful tales of haunted twins. I had to kiss Tom Knox and his borzois goodbye. As I was going to write from a female perspective, I didn’t want to put off any readers who might presume that a male writer could not carry a female voice. So I shifted sex. I became a gender neutral author.”

Thomas’s editor and agent were encouraging. He finally agreed that his books would be credited to SK Tremayne. “We were all in agreement. Partly for the reasons I state, but also because it arguably helps, these days, for fiction writers to be female, or at least not male.”

For many in the writing world, that last sentence of Thomas’s will land with a needle scratch.

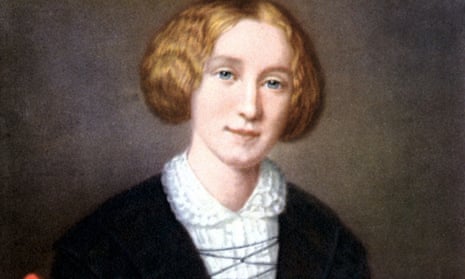

We often say that someone has “a face for radio”, meaning that the subject thrives on a medium that obscures their looks. And for a long time, in literature, there has been “a gender for fiction”, and that gender has been male. At least since Charlotte Brontë called herself Currer Bell, and Mary Ann Evans settled on George Eliot, women have taken male pen names in hopes that they will be taken more seriously by the reading public. In more recent times, the trend has been for successful authors to go genderless. Two of the world’s top-earning authors happen to be women and both go by their initials: JK Rowling and EL James.

“We have no way of knowing if Rowling would have done as well writing as ‘Joanne’,” says Suzie Dooré, editorial director of fiction at Hodder and Stoughton & Sceptre. “Still, Bloomsbury do say the reason they did it was that they thought young boys were less likely to read it under her full name.”

And complaints about sexism in the literary world are still very current. There is an entire organization, Vida, whose website tracks the pitiful representation of women.

But Thomas’s experience suggests a more complex situation. His new novel, Ice Twins, is climbing the bestseller lists across Europe. It is narrated by a freelance journalist named Sarah who, in the course of the book, gives birth to twins, suffers through the death of one of them, and then watches the surviving twin insist her sister is still alive.

Thomas doesn’t see much difference between this pseudonym and the last; they were both simply ways of selling more of his books. Knox, he says, was specifically chosen as mid-alphabet, to sit at eye height on bookstore shelves. “SK Tremayne was less militantly commercial,” he explains. “It had to be writerly and a name I was comfortable with, and Tremayne is my great grandmother’s maiden name. The S and the K just sounded nice.”

Steve Watson is another male writer who chose the gender-neutral route, publishing his bestselling novel Before I Go To Sleep as SJ Watson.

“My agent and I talked about using my initials and her not mentioning that I was male,” Watson says. “I wanted to reassure myself that the first person female voice was believable. If at least some people weren’t sure whether I was a man or a woman then it was working, and I was immensely gratified when certain publishers were convinced the book had been written by a woman.”

Thomas reports similar feelings when reviewed as a “she”. “Lots of readers, critics and bloggers have presumed I am a woman,” says Thomas. “That is pleasing as for some people I clearly managed to capture the female voice.” Watson says that some of his publishers chose to obscure things further by not using his photo and writing a gender-neutral biography. “That was their decision,” he says. “I didn’t feel I was hiding – my photo was on my website.”

Historical novelist Christopher Gortner sometimes goes by CW Gortner. “I write in a female voice in my novels about famous women, but I also write from a male perspective in my Tudor mysteries, so I’ve been straddling gender. It wasn’t until my first historical novel was published that I realised some people might question my veracity because of my gender,” he says.

His UK publisher decided to differentiate. “My foreign publishers use one or the other,” he says. “I’m never consulted. I don’t feel masked, and I just write my stories. I take the same risks.”

All three authors report generally positive experiences from reviewers, the publishing industry and fans alike. A Goodreads survey from 2014 suggests the instinct to mask his gender is a right one. It found, for example, that women are predominantly read by women – 80% of a new female author’s audience is likely to be female.

Thomas says he enjoys working in a female-dominated arena. “If men have decided they want to watch HBO instead of read, so be it,” he says. “Men can’t complain if the publishing industry is usurped by the gender that still cares about novels. I’m lucky to be surrounded by hugely talented women, from my editors to my agents: they are there because they are passionate, and clever, and committed.”

“Does it help to be identified as a woman, or to have no gender at all?” asks Thomas. “No one can say for sure, but it is certainly arguable. And given that every ‘debut’ novelist wants to give themselves every possible chance, why take the modest risk that using a male name might bring? Why not just use initials? Get rid of gender altogether?”

It is a suggestion of which even George Eliot herself might have approved.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion