Skylake processors that were discovered to be readily overclockable are having their speeds locked back down, with Intel shipping a new microcode update for the chips that closes a loophole introduced in Intel's latest generation of processors, according to PC World.

Intel has a funny relationship with overclocking. On the one hand, the company doesn't like it. Historically, there have been support issues—unscrupulous companies selling systems with slower processors that are overclocked, risking premature failure, overheating, and just plain overcharging—and more fundamentally, if you want a faster processor, Intel would prefer that you spend more money to get it. On the other hand, the company knows that overclocking appeals greatly to a certain kind of enthusiast, one that will show some amount of brand loyalty and generally advocate for Intel's products. Among this crowd there's also a certain amount of street cred that comes from having the fastest chip around.

To address this duality, Intel does a couple of things. Most of its processors have a fixed maximum clock multiplier, capping the top speed that they'll operate at. But for a small price premium, certain processors have "K" versions that remove this cap, allowing greater flexibility for PC owners to run their chips at above the rated maximum speed. This way, most processors can't be readily overclocked, but for those enthusiasts who really want to, an official option exists (although even with these chips, Intel recommends that people do not overclock).

All was well and good until Skylake came along. Late last year, Asrock shipped a firmware that enabled overclocking of even non-K Skylake processors.

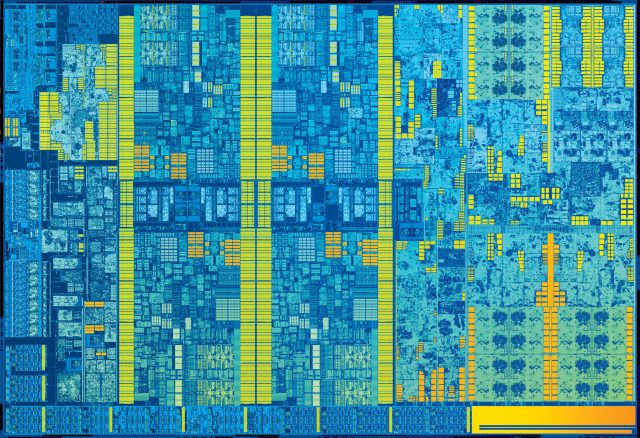

What made Skylake special is a change in how it generates the various clock frequencies that it uses for the processor's different components. A processor's clock speed is governed by two things: a base clock speed and a multiplier. A 3.5GHz processor, for example, might have a base clock of 100MHz and a 35× multiplier. In the heyday of overclocking, both the base clock and multiplier were often adjusted (though sometimes the processor had to be tricked into offering the full range of multiplier options). Base clock overclocking, however, was always a little more susceptible to problems, because the processor's speed isn't the only thing that's generated by that base clock. Other system clocks, such as the one used by the PCI bus, also tend to be driven by the base clock. As such, boosting the base clock meant that everything—not just the processor, but also RAM, the interface to your video card, the disk controller—had to operate out of spec.

Adjusting the multiplier was, therefore, the safer, better option for all but the most extreme overclocking. And that's what people did, until Intel introduced the K processors with its Sandy Bridge line. With Sandy Bridge, multiplier overclocking was off-limits unless you bought a K processor. The base clock was the only option, with the problematic side-effect of making everything run too fast.

Skylake, however, changes how the base clock is used. In Skylake processors, the clock signals used for things like the integrated PCIe bus and memory controller aren't derived from the base clock. They're separate, meaning that the base clock can be freely altered without pushing any other part of the system out of specification. This is what Asrock's firmware update took advantage of. Non-K Skylake processors have locked multipliers, but with the base clock now freely adjustable, a wide range of overclocking options became available. The only downside to this was that it meant disabling the integrated GPU, which presumably retains some base clock dependence.

Intel's update changes the processor's microcode—programmable code embedded in the processor that gets updated both by system firmware and operating systems—to, in some unspecified way, prevent altering the base clock in ways Intel does not want. While it will take some time for motherboard vendors to update their firmwares and actually propagate the new microcode to end-user systems, it means that the end is nigh for simple overclocking of Skylake processors. Some holdouts may stick with old, overclocking-capable firmware, but it will become increasingly hard to buy new motherboards that support the old capability.

None of this should have much impact on the K processors, which remain unlocked—and which will continue to attract around a 10-percent price premium for the privilege.

reader comments

77