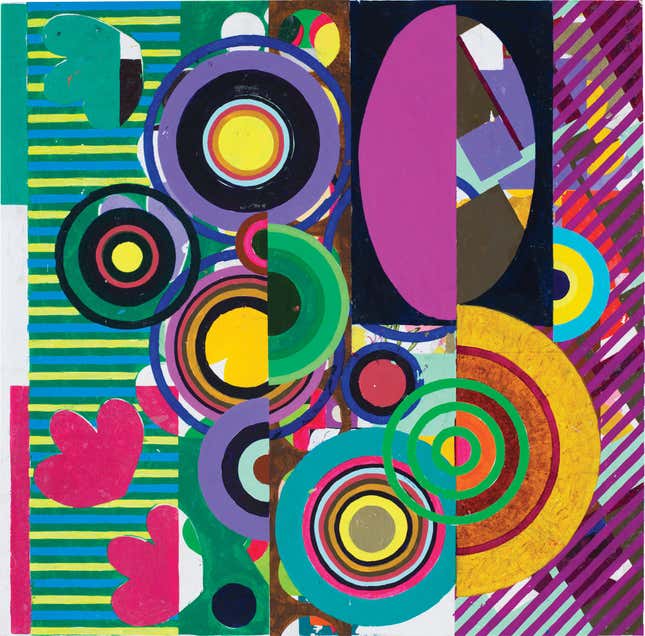

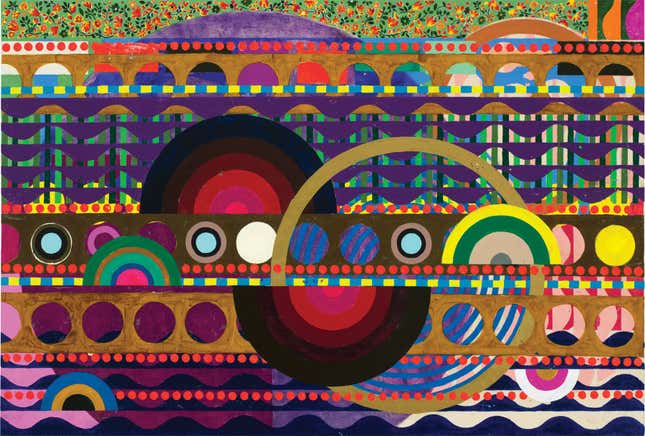

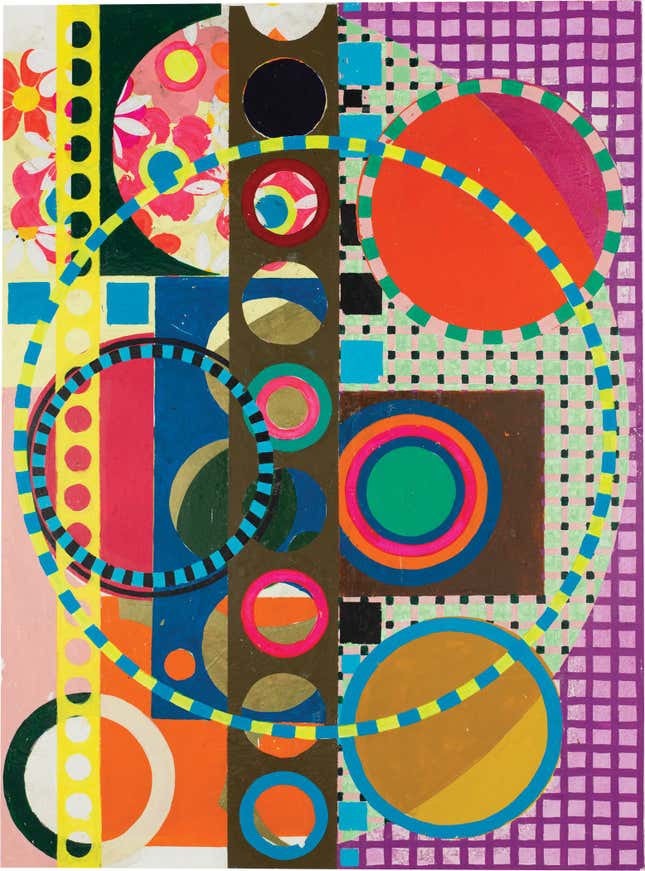

Brazilian artist Beatriz Milhazes stood beside one of her lush, vibrant paintings at the James Cohan Gallery in Manhattan, where her new exhibition, Marola, opened on October 22, and described the unique torment of creating it.

“It became kind of a mess, actually,” she said, describing how she left the painting for a show in Hong Kong only to return, barely recognize her own work, start nearly from scratch, and persist until one day a few small circles showed her the way out. “Even if it’s a painful process, it’s such a pleasure when you finally can see some light at the end of the tunnel. … And then from that point to the end, it worked quite fast.”

Work through it

Milhazes’ persistence is evident in her body of work, which has expanded and evolved over the last three decades, much like the marola—Portuguese for rippling waves—referred to in the exhibition’s title. In recent years, her paintings have set record prices at auction and the new exhibit—Milhazes’ first to include sculptures—comes on the heels of Jardim Botanico, a sprawling 2014 retrospective documenting 25 years of Milhazes’ work at Miami’s glossy new Pérez Art Museum.

The many joyous layers in Milhazes’ collages, prints, paintings, and sculptures obscure a terror familiar to anyone in the creative field: that of the blank page.

The key to working through it, said the artist, is just that: keep working.

“I always like to be in the studio and trying to make something happen,” said Milhazes. “I have a friend that says, ‘If something will happen, it will happen in the studio.’”

Experiment and explore

Milhazes’ need for momentum precipitated what has probably been the most important development in her career thus far—an original painting technique she calls “mono-transfer” that’s like a cross between monotype printing and temporary tattoo application. (See 2:50.) In order to achieve her signature precise, layered shapes in flat, opaque, and super-saturated colors, Milhazes applies acrylic paint directly to clear plastic sheets. Once the paint is dry, she presses it directly onto the canvas and peels away the plastic sheet, leaving the painted shape behind.

Chief among the technique’s many benefits, said Milhazes, is that it is less time and energy-consuming than painting directly onto the canvas, which means she doesn’t have to take as many breaks. It also allows her to compose paintings as she goes, piece-by-piece, rather than working from a planned sketch.

“Sometimes I find myself as a scientist,” said Milhazes, “introducing some new elements, new possibilities, and from this point creating kind of chain reaction … until one point that you see a completely different kind of composition.”

Milhazes brought the same improvisational style to her new sculptures, which bring the tropical rhythms and pleasing balance of her paintings into three dimensions—but not without their challenges.

Embrace the adventure—with co-pilot, if necessary

The sculpture “scared me, because I am a two-dimensional artist,” said Milhazes. “The way I don’t work with [a] sketch, it became super-complicated to develop something that’s physical and not have a plan.”

Milhazes said enlisting a partner who was similarly comfortable working without a map was key. That’s where Jean-Paul Russell, the co-owner of Durham Press, the Bucks County, Pennsylvania, studio where Milhazes has produced prints since the 1990s, came in.

“That was the first thing I told him: It is an adventure,” she said. “I don’t know if I will make something happen.” That didn’t keep her from working with Russell over five years to develop architectural expressions of her famous paintings, which now hang in the James Cohan Gallery. The artist gestured to one of her freshly installed sculptures.

“When I first saw this,” she said, “I thought: ‘I did it. I made it.'”

But that doesn’t mean she’s going to stop.