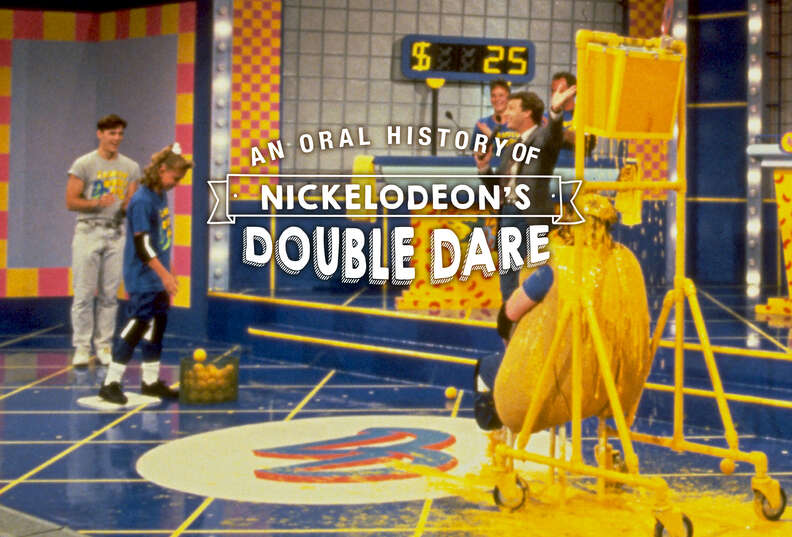

An Oral History of Nickelodeon's 'Double Dare'

As the entertainment industrial complex continues its methodical excavation of the collective cultural memory of ‘80s babies, Nickelodeon heralds the arrival of "The Splat," a late-night and online programming block devoted to the network’s ‘90s highpoint, which launched October 5 on the TeenNick channel. Thus far, Nick has announced a blend of undisputed Pog-era classics like Are You Afraid of the Dark and Ren and Stimpy, plus plenty of shows that don’t hold up as well, or at all, but we’ll watch anyway, because it’s 2 in the morning and we are too stoned to remember how to use BitTorrent.

But there’s a glaring omission. What about Double Dare? In many respects, Nickelodeon owes its erstwhile stranglehold on the children’s cable market to the show, the first smash hit Nick produced in-house. Combining trivia questions, absurd physical challenges, and revolting and occasionally treacherous obstacle courses, Double Dare poured a reservoir of slime on the well-worn trivia show formula. More importantly, for those of us whose parents constantly gave us flak about our unkempt bedrooms, the sight of other kids getting rewarded for making as big of a mess as possible vicariously fulfilled our most depraved and antisocial impulses.

What follows are the recollections of Double Dare’s creators, stars, and crew members, from the events leading to the show’s debut in 1986 to its final new episode in 1993. (Not counting the ill-fated Double Dare 2000.) Turns out they all had a pretty great time! Even when the stench became overpowering, the set was a death trap, a neo-Nazi took a shine to Marc Summers, and some of the kids’ parents turned out to be lawyers.

Part 1. “Wouldn’t it be fun if you made a big Rube Goldberg machine, but instead of a ball, it was a person?”

Mathew Klickstein, pop culture historian; author of Slimed!: An Oral History of Nickelodeon’s Golden Age: You saw this with MTV. You saw this with SNL. You saw this with other artistic or musical movements, like punk. It’s the inevitable cycle where there are young people working kind of under the radar, putting something out there that they’re frustrated isn’t out there already. A lot of it comes from a beautiful naiveté -- they don’t know that you “can’t do it like that.” It goes back to someone like Steve Jobs saying, “I’m not going to listen to you saying I can’t do this. This can be done. We’re going to make it happen.” And then we have Apple, or in this case, we have the golden age of Nickelodeon.

Geoffrey Darby, co-creator and executive producer of Double Dare; senior vice president of programming and production at Nickelodeon from 1981 to 1993: A production group approached Nickelodeon with Nabisco in tow. Nabisco thought a game show would be a good way to sponsor television for kids that wouldn’t be the animated stuff, because what are you going to animate for Nabisco, y’know? Nabisco makes cookies. They don’t sell toys or whatever.

Michael Klinghoffer, co-creator and producer; vice president of production at Nickelodeon from 1980 to 1990: A consulting group approached Gerry [Laybourne, then-president of Nickelodeon] about doing a kids' game show, and she said, “Maybe if it’s any good.” So we looked at their runthrough, and some of the staff members didn’t particularly like it. So we went to Gerry and said, “If we’re going to do a game show, can you give us a chance to create one that works better?” And she said, “Sure. We’ll have a lunch in my office, invite anybody who wants to come, and we’ll talk about game shows and see what comes out of it."

Klickstein: They were bringing as many people together as they could at that little office to ask, “What do you think?” Secretaries, receptionists, anyone they could ask. Luckily, there were people there who grew up on game shows and could say, “This should work like this, and this should work like that.”

Gerry Laybourne, president of Nickelodeon from 1980 to 1996: In the office, nobody was hierarchically more important than anyone else, but the team that did Double Dare was Dee LaDuke, Bob Mittenthal, Mike Klinghoffer, and Geoffrey, who was the only person who’d ever produced anything before.

Darby: I remember telling the group the three rules of game shows: it is 40% game, 50% jeopardy, and 10% production value. It was important that people were able to play along at home, and what I mean by “jeopardy,” is there had to be something at stake, we made money at stake, or else the audience would ask, “Why do we care?”

Bob Mittenthal, co-creator; children’s TV writer/producer: The idea to “make it messy,” came afterwards. It was just kind of a natural outgrowth of thinking, “What could we do for a dare?”

Darby: One of us, I don’t know who, maybe Dee, said she had always loved a board game called Mouse Trap. It was basically a Rube Goldberg machine. We thought, “Wouldn’t it be fun if you made a big Rube Goldberg machine, but instead of a ball, it was a person?”

Part 2. The Host; or, “You are so desperate this is scaring me”

Laybourne: Geoffrey watched something like 1,200 tapes, or did something like 1,200 interviews [looking for a host]. It got down to one point where he wanted to audition my husband -- who believe me, would be the worst possible host of any kids' show. It was like, “Geoffrey, you are so desperate this is scaring me.” I think we found Marc Summers something like two weeks before we went into the studio.

Marc Summers: I grew up watching Bob Barker. I was a Price is Right freak and a Jeopardy freak. Back then, NBC, CBS, and ABC would have game shows on from 9 in the morning until 12 or 1 o’clock in the afternoon. When you were sick from school with chickenpox or faking it, you would sit home and watch game shows all day. I was just mesmerized by that whole situation. Bob Barker was a star, Bill Cullen was a star, and Jack Barry was a star, and I thought, “What a cool way to make a living.”

Darby: Marc was a magician. He was actually a member of the magicians' league, y’know? He was a real bona fide magician. He had an ability to connect with both kids and adults, because magic is often done that way. That was an interesting benefit, and it put him on top of the heap.

Summers: My first job in LA was a show called Truth or Consequences, which Bob Barker hosted. I was hired as an idea man to work two days a week and make $300. In 1974, I thought I had died and gone to heaven. Then I worked on a bunch of other game shows, long before Double Dare happened.

Laybourne: Marc was well worth waiting for, but it was down to the wire.

Summers: Everybody I’ve ever met says they auditioned for that job. But here’s the story I got: they initially wanted Soupy Sales to do it. Then it worked out that he was too old, according to the story I was told. And I was told they had offered the job to Dana Carvey on the same night he got the SNL offer. He took SNL. I’ve always meant to thank him for that.

Laybourne: The thing to me that’s so amazing, is Marc never told us anything about his OCD. He never complained. He never mentioned it. When you think about the fact that this guy put himself through being the host of the messiest game show in the world, that’s pretty amazing to me.

Summers (on The Oprah Winfrey Show in 1997): “It was like a bad sitcom. There I was hosting a television show where people were throwing green buckets of goo on each other, and I was having a good time, but you take what was going on on that show and multiply it... If you watch the first 65 episodes, I never got a drop on me. The kids would be over there just consumed in whipped cream and chocolate, and I would be over here. And at some point the producers came to me and said, “You know, you really do have to participate as much as possible.”

Summers: All that OCD stuff has been blown out of freakin’ proportion. I dealt with what I dealt with. I wasn’t going to let my OCD screw up my opportunity to host the kind of show I had always wanted to host. Yes I have it, yes I lived through it, but I never let it affect the show in any way, shape, or form.

Part 3. The Rules; or, how to punish youthful ignorance

Mittenthal: We decided that if we were going to do a trivia-based game show, we didn’t want there to be a punishment. We didn’t want to embarrass kids for not knowing an answer. So physical challenges were a way to make it okay to not know. I think there were even times when kids knew an answer, but wanted to do a physical challenge.

Darby: That’s a myth, that we created the physical challenge so you never had to give a wrong answer. No we didn’t. That was made the way it was so we could put physical challenges intermittently throughout the show, so you never knew when a physical challenge was going to happen, and you had to watch the whole show. You couldn’t come in 10 minutes after the first commercial break when you knew the physical challenge round was happening.

Alan Silberberg, head writer from 1986 to 1989: I had just gotten out of grad school, so I buzzed Geoffrey Darby. He said, “Okay, we’ve got this game show coming up. Do you want to write questions for it?” I wrote probably like, 10 or 20 questions, and they liked what I did. I wouldn’t just write straight trivia questions. I would say, “Wouldn’t it be funny if I was doing Brady Bunch math? Add Brady Bunch kids with the kids from Who’s the Boss? and how many kids do you get?” I created the order of the questions: “This one they should be able to catch,” “This one they might be able to catch,” and “This one better go to physical challenge or oh my God...”

Darby: Question one was easy, question two was harder, and question three was impossible.

Silberberg: When it came time to tape the first batch of shows, they realized they didn’t have anybody to coordinate the questions, so they asked me if I would come to Philly [where the show was being shot] for “a couple days to help organize things.” And I remember being locked in my hotel room, and Marc and Mike Klinghoffer came up to see me, and said they realized they didn’t have rules written, didn’t have any copy written, and needed a head writer.

Summers: [And] we were looking for a sidekick. John Harvey was the number one radio morning man in Philly for a while, and had just been fired.

John Harvey, “Harvey the Announcer”: I’ve lost two parents. I’ve been through divorce. I’ve been through a lot of crap, but nothing was as painful as getting fired from my radio show. I had been so successful at one point at WIOQ [in Philadelphia], but my ratings were falling along with the station’s, and when the ratings start to go in the tank, they fire the head that’s sticking out. And it was only maybe a month prior to that, Double Dare started planning on coming down here to Philly to shoot because it was cheaper than New York. One the of PAs was a fan of mine, and she heard them talking about needing an announcer, and said, “I know somebody!”

Summers: One of the producers called him, and we got along instantaneously.

Part 4. “It was a complete disaster”

Dana Calderwood, directed bulk of series: Nickelodeon had sort of begun the franchise of slime with You Can’t Do That on Television. They had the gag where if somebody said, “I don’t know,” they’d be slimed. That began to proliferate through other shows and promos, and was becoming a Nickelodeon trademark. So the thinking was, “Let’s take that to the Nth degree.”

Robin Russo, stage assistant: When I first got the job as a production assistant, I was looking at the layout of the show, and -- I’ll never forget -- I said, “Are you kidding? This isn’t going to go!”

Klickstein: There were people who were doubtful. Marc Summers was one of them, actually. There were others just asking, “Are young people really going to want to jump into a vat of disgusting baked beans?” Or, “Are they going to want to slide down into a pool of whipped cream and ice cream and hot fudge?” There wasn’t a precedent set for it, necessarily.

Darby: I remember telling the set designer, Jim Fenhagen, that I wanted it to be like a natatorium, because I liked the word. That’s an indoor pool. That’s what I wanted it to feel like -- with tile, and vents so we could squeegee all the stuff off the stage without stopping production, because we had to make so many shows in a day.

Laybourne: We had a very tough economic proposition. We had to produce the show at $12,000 per episode, which meant we had to do four shows a day.

Summers: Eventually, we got up to six or seven shows a day. Six was the average towards the end.

Laybourne: For the first show, I was standing off to the side watching as kids walked into the room for the first show. They were just in awe. I honestly did not know kids knew so many swears. They came in and they were like, Oh shit, I can’t believe this.

Klinghoffer: The very first show was a complete disaster. We got to the obstacle course, and the first obstacle was a flag in this bag of feathers. The kid literally spent the entire 60 seconds looking for the flag. Turned out there was no flag. Someone forgot to put it in the bag. For take two, we put the flag right on top to make it easy. Because the kid was so frustrated from the first time, he took the bag and turned it completely upside down, so the flag went to the bottom, and he ran out the clock searching for the flag again. The third time we put five flags in it, and he found one in like 10 seconds. Then the cameraman slipped and fell backwards, and then we were shooting the lights.

Laybourne: By the end of the day, we had only shot one show. It really looked like we were dead.

Klinghoffer: The network execs must’ve been thinking, “Oh my God, what have we done?” But I got a message from Gerry, and she said, “I’m proud of you guys, you’re doing a good job. I know the first day is always hard, but the show looks entertaining as hell, and it’s going to be great.”

Gerry Laybourne: That wasn’t me. I was panicked.

Part 5. Vindication through gak; or, “sex for kids”

Laybourne: We premiered on a Monday with a .6 share of the ratings. By Thursday, we had, I think, 1.8. Two months in, we had 5.6. It was all word of mouth. We had no marketing. It was lightning in a bottle.

Darby: The obstacle course round tested 10 out of 10, the physical challenges tested nine out of 10, and the trivia round tested four out of 10.

Russo: After the first show, I remember saying, “This is going to be huge. It’s like a big birthday party.”

Mittenthal: One of the executives referred to the messiness as “sex for kids.” I think what she meant by that was it’s just sort of -- I’m going to use the word wrong -- but I’m going to say “sensuous,” just meaning the physical senses, the physical immersion. And it was so taboo. You could never do the kinds of things they did on Double Dare at your house.

Darby: I wanted to prove to the stage crew that nobody was above cleaning up. I remember getting on my hands and knees and vacuuming the floor after an obstacle course, and I made sure the other producers helped too. You can’t just stand around and watch the crew slave. If you make the mess, you have to clean the mess up.

Russo: If a physical challenge was something like putting a cup in your mouth and having someone throw a marshmallow in it, those were easy to clean up. When we did a real messy physical challenge, that was difficult, because the crew had 30 seconds to get the props off stage, and I can’t tell you how many times they fell. There was whipped cream and gak and all kinds of crap everywhere.

Calderwood: What would happen sometimes is by the fourth show of the day, the floor would become so slippery that camera people would just lose their footing and jump right back up, because no matter how often you cleaned it, and steamed it even, the floor was endlessly slippery. So we would slide on it, shuffle step. You didn’t pick your feet up. That’s how you maintained your balance.

Silberberg: Nobody knew how we were going to do this show. I said, “We need more physical challenges! We’ve gotta mix them up! Who’s going to oversee that and test them? Okay, I’ll do that.”

Darby: We tested physical challenges in the evening after the show, when most of the people had gone, like the camera crew. We did them forwards, backwards, then blindfolded.

Calderwood: When we rehearsed the stunts, or tested them, it wasn’t just the stunt team. Everybody would come by. Harvey would have an idea. Marc would have an idea. I would have an idea. PAs would have ideas. Interns would have ideas. One time we were sitting around eating Chinese food. Somebody said, “Let’s do a stunt with Chinese food.” So Byron [Taylor, set/production designer] unfolded a takeout container, and just based on that, he designed a giant human-sized takeout container that a kid could wear. The ideas would just come from anywhere.

Silberberg: I remember visiting this tiny basement place where they were building the giant nose. Another time, we were up in the writers’ suite. We looked out this window, and there was this huge slice of Swiss cheese being carried across the street. We said, “What are we doing?” It was the weirdest job I’ve ever had.

Summers: When we tested physical challenges, all of our inside jokes became sexual. This was a -- shall we say -- little bit more innocent time, in ‘86, ‘87, and ‘88. We got away with just laughing to ourselves, and the kids had no idea why. If there had been Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, God knows what at the time, we would’ve all been out of work. Everything became a dick joke. “If you do this, the fountain will erupt,” y’know? It got ridiculously filthy. We never said “penis,” “vagina,” or “cum,” or anything in front of the kids. But when we looked at each other, or got over to a corner, it was, “Look at that gigantic penis! It looks like a mountain just cumming!” It was a frat party.

Silberberg: Sometimes when we tested things with our adults, if kids weren’t around, Marc might make a blue comment. Aside from that, I have no memory [of raunchy humor].

Summers: We didn’t know master control was recording everything. Somehow, Gerry found out back in New York that there was a tape circulating with the writers and the host turning everything into a dick joke or a vagina joke or something, and we had to stop.

Harvey: I had never done anything for kids. I had only worked for adult audiences. So during the first two weeks, I was giving them so much over-the-top energy -- a lot of that “Heeeey kids!! How ya dooooooin’?!” bullshit, y’know? Within those first two weeks, I had a kid in the audience look me dead in the eye -- and the room was silent, keep in mind, aside from me talking to the audience -- the kid looks me dead in the eye, and mocks me. He says exactly what I said in the same clown-ass tone that I said it, and it was humiliating. I was reduced to the size of an ant, instantly.

That kid did me the biggest favor ever, because I realized, “Oh my God, I am bullshitting these guys! They know fake energy when they see it!" You can’t bullshit kids at all -- they have instant bullshit detectors. So I thought, “Okay, from now on, I’m going to talk to them like they’re grown-ups.” I talked to them like they were hip, smart, and my peers, and they were disarmed by the fact that I treated them respectfully. I only had to throw out one kid in 600-plus tapings. One kid, one time. My memory of it is he did something to another kid that I knew was crossing the line -- he must’ve hit somebody next to him, or whatever.

Part 6. Tell them what they’ve won!

Summers: We toured it out for eight years. We did 40 personal appearances a year. We would do the Palace of Auburn Hills and sell out 20,000 people on a Saturday. Then Sunday we’d go to Toledo, Ohio, and sell that out. We would generally do Friday, Saturday, Sunday. Sometimes we did two shows in one city. It was like being a rockstar for kids. It was nuts.

Russo: Marc always did the huge road shows, and I was always with him on those. There were smaller versions, too, where Harvey and I would go out, or it would be Dave [Shikiar, stage assistant] and I. You’d show up to the city, you’d stay in the nicest hotels, you’d get the nicest dressing rooms. But what not everyone remembers is, Marc was huge. He couldn’t go anywhere.

Harvey: There was one time we were playing in Central Park, doing a live version of the game for some promotional thing. I don’t know how many kids there were, but there had to be tens of thousands. After the show, we had security guards rush us from the stage, push the kids out of the way, and hurry us into a waiting limo. Then we pulled away, and the kids were screaming and beating on the trunk of the car. We just laughed, and went, “Wow. We’re the freakin’ Monkees.”

Summers: We did these meet-and-greets before the live shows. One time this very hot, sexy woman came over and said, “Can I take a picture?” And just as they were going to take the picture, the woman stuck her hand down the back of my pants and grabbed my ass -- my actual ass. When she was leaving she said, “My husband’s a cop, but he works midnight to 8 in the morning. Here’s my phone number and address, you should stop by and see me.” And I’m thinking, “Yeah, your husband’s got a gun, so that’s a great idea.”

Part 7. Broken bones, dysfunctional families, prison inmates, lawyers, Nazis...

Summers: The kids were great. It was when it became Family Double Dare that a few of the parents became idiots -- especially when we started doing the nighttime versions when we gave away cars and trips to God-knows-where. A kid would miss the flag with two seconds left, and there were times when we had to separate a parent and a kid, because the dad would be holding the kid in a chokehold saying, “Damnit, I needed that car! I can’t believe you didn’t get that flag!”

Harvey: The kids didn’t give a rat’s ass about the prizes. They just wanted to jump into the goo.

Russo: There was always one parent who did something stupid, saying, “My kid should’ve won the bigger prize!” and so on.

Harvey: Sometimes the family dynamics didn’t make you feel so comfortable. You felt bad for the kid. It was like, “Wow, I bet that kid has a really terrible life at home with the kind of emotional spleen-venting they’re putting up with.” But most of the time that didn’t happen. We would audition people, and the talent coordinators would get rid of people they thought were mean or way too competitive.

Calderwood: Aside from the first episode, I don’t think we ever stopped an obstacle course, except for one time a kid broke his arm.

Summers: We always asked kids on the affidavit before the contract, or whatever the release form was, “Have you ever had any broken bones?” One time we did an obstacle course -- “on your mark, get set, go!” -- the kid runs from obstacle one or two, he falls, and the bone breaks and goes right through his skin. I walked out of the studio, it made me so sick.

Russo: His arm was in an “S.” He was losing it, this kid. Everyone was panicking. I don’t remember all the details, but I do remember going over and taking him under my wing. Then the nurse -- we had to have a nurse on set at all times, we couldn’t have done that show without a nurse -- the nurse took over from there.

Summers: Our legal team did some research, and found out the kid had a disease that was like glass bones, and had broken his arm like 10 or 12 times.

Calderwood: They did medical forms and history to allow you to become a contestant, and he clearly wasn’t a candidate, and he knew it himself, but he just so loved the show that the lied so he could get on. I think he was more disappointed that he let the show down, in effect, than he was concerned about hurting himself. We all felt terrible for the guy.

Summers: We had another show where a kid was going through an obstacle called the Sewer Chute. He went up a ladder, then had to come down another ladder. When he went up, the kid tripped, and he came flying down. I swear to God, I thought he broke his head. You can hear me going, “Are you okay?! Can you finish the rest of the course?!” The fact that this kid’s head didn’t come off is amazing.

Klinghoffer: We used to kid around: “Uh-oh, that kid’s family is lawyers.” But we were really more kidding.

Summers: The kid’s father was an attorney, and he said, “Look, my kid only got to obstacle number six because of what happened. Number seven was the big-screen TV. If you don’t want me to sue you, give my kid the big-screen TV.” Which we did. After that, when we went through everyone’s release forms, if a kid had a parent who was an attorney, we didn’t let them on the show.

Russo: People would write letters. There were a couple times me and Marc were threatened.

Summers: Prisoners used to watch us, and I know they used to send her... If you’re in prison and you see a voluptuous girl going through green slime, chances are you’re getting your rocks off somehow. She got a lot of that kind of mail.

The worst thing that ever happened to me was when I was playing a theme park in San Jose, and I would always go through the audience and pick out people, just spontaneously. So I’m doing the show on Saturday, and there’s a grown-up, like in his 30s, wearing this gigantic swastika around his neck. Forget that I’m a Jewish guy, it’s kind of politically incorrect to be wearing a swastika. So I’m doing the first show at 1 o’clock, and he’s jumping up and down -- “Marc, pick me! Pick me!” -- I don’t pick him.

The second show, I go out, and he’s in the same seat somehow, jumping up and down with his flapping swastika -- “Marc, pick me!” -- and I didn’t do it. When I come back for the Sunday shows he’s in the front row, and I don’t pick him. He stands on his chair and yells, “You dirty fucking Jew! I’m going to kill you, you motherfucker! I come here for three shows and you don’t pick me?!”

They wouldn’t escort him out of the park, which I would not believe. I finished the show and said, “I’m not doing any more shows until you get this guy out of the park.” And they finally escorted him out.

Part 8. The food problem; or, hundreds of pounds of rotting beans

Russo: A couple times people got serious because we were “wasting” “good food,” and all that stuff.

Klinghoffer: The food waste issue was an absolutely ridiculous non-issue. I can say it now. I’ve never heard anyone say, “Look at that movie Animal House! Look at how much food they wasted in that food fight! Oh my gosh! We should ban that movie!”

Harvey: We got the occasional complaint about wasting food which, y’know, was not an illegitimate grievance. It did look like we were just throwing lots of food around when people were unbelievably hungry in America, but we would try to use post-dated surplus stuff. If it’s past the date on the can, you can’t sell or distribute it, even if it’s not rotten.

Klinghoffer: The food was props. It wasn’t really food. Starving people aren’t going to want to eat a lot of whipped cream.

Harvey: You know that tank we filled with Styrofoam peanuts or balloons, or sometimes water in the obstacle course? It was pretty long -- 15 or 20ft -- and we’d fill it with various crap. One time we filled it, like, I dunno, a third of the way up with baked beans. When you empty that many baked beans into a tank, you want to get your money’s worth, so we shot a week’s worth of shows with the baked beans. At the end of the week, shooting day in, day out, under hot lights, it was pretty ripe.

Russo: To get rid of the baked beans at the end of the week, we called the guy with the honey wagon. So he parks out around 7th St in Philly where the WHYY studios were, and runs this big hose in, and sucks that tank dry. As he was finishing up he said, “You know what I do for a living, right?” And we said, “Yeah, you suck shit out of the ground.” And he said, “This is, by far, the most disgusting thing I’ve ever had to do.”

It was like, “Wow. We have achieved immortality. We grossed out the honey wagon man.”

Part 9. A legacy of benign disarray

Summers: In the cable world, if you do 100 episodes, they generally cancel you, because then they can rerun the hell out of them. We did 525 episodes, and after a while, how many more do you need to do?

Russo: Y’know, when the show got canceled, if I’m not mistaken, we were still doing the road show, so it wasn’t really canceled for us. But that show had another 10 years in it. To this day I’ve said they should recreate that show, and bring it back with Marc as the host.

Summers: It’s 30 years later, and we’re all still friends. The whole situation was sort of a magical right time, right place.

Klickstein: It set the tone for how all the other game shows would be established. There wouldn’t have been Nick Arcade without Double Dare. There wouldn’t have been Legends of the Hidden Temple without Double Dare. There wouldn’t have been What Would You Do? or Don’t Just Sit There. It set the tone not only for Nickelodeon game shows, but for kids’ game shows overall.

Summers: For whatever reason, Viacom won’t do it again. I get requests for it constantly. It was a major part of a lot of kids’ lives who are now in their 30s. But, y’know, my hands are tied. I don’t own the program. I own a percentage of it, but not enough to make a difference.

Laybourne: Nickelodeon has the problem all big businesses have, which is huge expectations of quarterly earnings, and right now there’s a very fluid marketplace where kids’ behavior is changing faster than they used to change channels. When I left Nickelodeon we had 56% of all kid TV viewing. That was the end of 1995. I have no idea what the percentage is now, but we had virtually no competition. Cartoon Network had just reared its head. Disney was airing Eisenhower documentaries and Dumbo in the same time slot on different days of the week. They were nowhere. So Nickelodeon created this category of kids’ cable that looked lucrative, and lots of people rushed in...

Summers: It put Nick on the map. Nick was a floundering network with some bad puppet shows on it. And then we came along.

Calderwood: Bob Mittenthal and I once talked to Spike, and said, “What do you think about doing an adult version of Double Dare?” We could do challenges that would be big -- Survivor-like. They thought about that. One time Marc went to Nickelodeon and said, “What about doing a live road show?” But they decided against it. There’re a couple of possible explanations. One is they’re protecting the brand. It was such a big success and such a cornerstone of Nickelodeon, what would they have to gain by redoing it?

Silberberg: This feeling that Double Dare gave me -- it wasn’t just confidence, but there was a camaraderie and sense that a job could be fun and rewarding and you can make great friends. It was my first real job in my mid-20s. Everything you hope jobs could be, I got right off the bat.

Calderwood: We would get contestants coming off set, and sometimes audience members, saying, “This is the best day of my life!” On the one hand that’s kind of sad, but they were only kids at the time. You tend to look down on kids' programming when you’re a young working professional and you want to hit heights, but you come to learn that there’s nothing cooler than doing something for kids.

Russo: I’ve shown my teenage kids Double Dare. My daughter thought it was really cool, but my son walked out of the room shaking his head, saying, “I don’t know what you were doing.” One time, I don’t think he realized he had put it on, but in eighth grade he wore a Double Dare T-shirt to school, and the teachers and some of the kids went nuts. He said, “Mom, I didn’t know they knew who you were. I didn’t realize how big that show was.”

Then I showed him another episode, and he said, “I still don’t know what the hell you were doing. Please don’t show my friends that.”

Sign up here for our daily Thrillist email, and get your fix of the best in food/drink/fun.

Barry Thompson covers pop culture and music. His work has appeared in The Boston Phoenix, Esquire.com, Paste Magazine, and several other online and print publications. He lives under a bridge in Allston, MA, with a cat. Follow him: @barelytomson.