The Einstein Myth

The story has become lore.

Albert Einstein was a rebellious student who chafed against traditional schooling and earned bad grades. After his university education, his brilliance was overlooked by a conformist academy who refused to give him a professorship. Broke and unemployed, Einstein settled for a lowly job as a patent clerk.

But this turned out to be a blessing in disguise. Free from the bonds of conventional wisdom, he could think bold, original thoughts that changed the world of physics.

The reality, of course, is more complicated.

Einstein was a rebellious student, but he always received exceptional marks in math and physics in school and on entrance exams.

Einstein did struggle after college, but he wasn’t turned down for professorships. What he failed to obtain after graduation was a university assistantship — which is, roughly speaking, a way to fund a graduate student while he or she works on a doctoral dissertation (like what we now call a research assistantship in American graduate education).

This was not a case of his brilliance being ignored, because Einstein was too early in his education to have done anything brilliant yet (the paper on capillary action he published the year after his graduation was mediocre). The main reason for his assistantship rejection was a bad recommendation letter from a professor who didn’t like him.

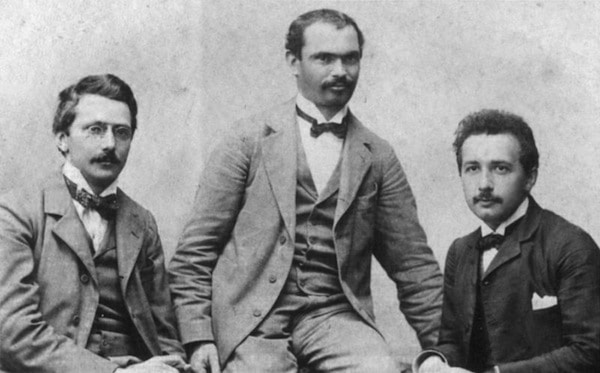

The key detail often missed in this story is that while Einstein was a patent clerk, he was continuing to work toward his doctoral degree. He had an adviser, he was reading and writing, he met regularly with a study group (pictured above).

The same year Einstein published his ground breaking work on special relativity (1905) he also submitted his dissertation and earned his PhD. Soon after he received professorship offers, and his academic career took off.

In other words, Einstein had to work a job to support his family while earning his PhD (an exhausting turn of bad luck), but his career from university to graduate degree to professorship still followed a pretty standard trajectory and timeline.

The Conformist Path to Innovation

The reason I’m telling this story is because it underscores a common habit: we like to cast innovators as outsiders who leverage their freedom from tradition-bound institutions to change the world.

In reality, innovation almost always requires long periods of quite traditional training.

Einstein was brilliant and original, but until he finished a full graduate education, he didn’t know enough physics to advance it.

The same story can be told of many other innovators.

Take Steve Jobs: the Apple II was lucky timing; Jobs didn’t become a great CEO until after spending decades struggling to master the world of business. Once his skills were honed, however, he returned to Apple and his brilliance had an outlet.

This is the hard thing about innovation. If we want to encourage people to change the world, we have to first encourage them to buckle down and work inside the box.

The tricky part is embracing this necessary conformity while somehow keeping that spark to think different alive long enough for you to get good enough to do good.

Interesting! Currently reading for my Phd dissertation and the emphasis is innovation and to think outside the box! We forget we need to know whats inside the box before we look outside it!!

A student may feel stifled by the rigid structure of a PhD program, as it limits the topics he may pursue and the scope of his research. But I argue this constraining structure is a good thing: it allows the student to focus and learn deeply the material and skills in his field, without the nagging concern that he must be ‘bold and creative’. It prevents students from trying to innovate without the prerequisite knowledge (and wasting time pursuing dead ends other people have explored already). 5+ years of doing grunt-level research builds enough knowledge to push the boundaries of science and ruminate on novel ideas.

Think of a high school kid trying to come up with breakthrough research in physics. Nearly impossible. The most he can do is reinvent the wheel. The same dynamic is at play for an undergrad before going through graduate school and being immersed in research for 5+ years.

Nice thread, really enjoyed it. Margaret, i’m 110% agreed with you…well said.

You hit the nail on the head with “the tricky part”. So many institutions seem to have as their sole raison d’etre crushing that spark. If your spark burns hot enough to survive, you will suffer within that institution. If you dampen the spark, you might have an easier time in the box, but so what? because the spark is gone. So while I agree with the need to work from the inside out, that tightrope act can only be successfully managed by the rare few, and even from them, it often exacts a large cost.

This is the story everyone tells, but I don’t buy it. Are institutions really trying to stamp out inspiration in brilliant, but misunderstood individuals? I haven’t seen much evidence of that.

The tricky part to me is that it can be frustrating to maintain the drive to do something new and different through a long period where you’re not able to act on it yet. This seems to take a lot of self-confidence…

Living through this right now.

I don’t know if this is an aberration – and by no means do I consider myself a genius, but I can at least testify that there is a “breaking” system in corporate america – atleast in the area of it I work.

Good article though – I agree to the concept, and agree to the fetishization of the “lone maverick” who works outside the system.

I am also living through this right now. I tried too hard to be novel and groundbreaking at the dissertation phase. I almost couldn’t help it, even though I knew the dissertation should be more like a rote exercise. Over time I understand better the need to go through the motions. After all, I don’t know that I can even do that yet. If I successfully finish the dissertation, that will be proof. Until then, what makes me think I even have the ability to do something more profound?

what would you say about zukerberg ? what would you say about plenty of fifteen year odd young kids who have their own startups and doing good from their first go ? Why do i start getting this feeling that you are only selecting examples that fit your theory , one contradictory example can ruin it.

The real world is full of stories all inclusive of people who put 10,000 hours before they become successful, people who are successful doing right thing at right time and being with right people (which some people call luck ), people who did follow their passion and become successful etc. Multiple theories could be true (Integrative Pluralism) . There could be many different phenomenons working for people become successful and make a difference .. Just my 0.02 cents

I agree that many different forces can matter in something as general as innovation. But I’m pointing out here what I think to be a particularly important force that is often (not always, of course) present, but is also often overlooked because it stands in contrast to our culture’s interest in the storyline of outsiders bucking tradition as the source of innovation.

As for Zuckerberg: launching thefacebook.com was not an act of brilliance. It was like many other social networks of the time and there were no breakthroughs in the underlying technology. Launching google.com, by contrast, was more brilliant, as it relied on a whole new way of approach information retrieval. It also required Sergey and Larry to get pretty far in a traditional computer science education before they could pull together those pieces.

One sidenote about Mark Zuckerberg: He got a business coach to help him in the days of Facebook’s early success (after opening it up to the public), when it became clear that he couldn’t handle managing a large business.

I don’t remember the exact article but it was reported at the time. A quick search turns up Fast Company’s post which mentions it: https://www.fastcompany.com/1822794/boy-ceo-mark-zuckerbergs-two-smartest-projects-were-growing-facebook-and-growing

So, point being: even those who succeed earlier also need help later.

Google wasn’t that brilliant. It derived from a pre-existing model of tracking citations of academic articles. It was just a new application of an old idea. That’s innovation too but maybe the brilliance was the refusal to sell to Excite for a million dollars, at a time when that looked like a good deal.

I take your point, but don’t completely agree. PageRank is one of those innovations that sounds straightforward when summarized, but the mathematics behind why it converges, and the technology innovations required to implement it efficiently on something as large as the web, was, to the best of my understanding, a big leap.

That reminds me of all the people who look at Sara Blakely’s success and say, “So what? All she did was cut the feet off pantyhose.” And it’s not like shapewear didn’t exist in the past (otherwise known as girdles). A lot of great ideas are old ideas applied in new contexts. That’s how creativity works. Not to mention, the idea is only one part of the ‘great’. The other part is the willingness + ability to execute.

Cal, it sounds like you’re saying in this comment that innovation is only real if it leads to a scientific/technical breakthrough (like Google with information retrieval). Clearly Facebook was a business innovation, as it resulted in a multi-billion dollar company that became the dominant social network.

Can it be innovative to find and successfully exploit a market? To quote Paul Graham: “Starting a startup is thus very much like deciding to be a research scientist: you’re not committing to solve any specific problem; you don’t know for sure which problems are soluble; but you’re committing to try to discover something no one knew before. A startup founder is in effect an economic research scientist.”

Maybe this is another instance of the “value of college” Newport vs. Graham debate (https://calnewport.com/blog/2007/09/06/dangerous-ideas-sorry-paul-graham-i-think-it-does-matter-where-you-went-to-college/). I think tech startups are an area where the value of the traditional approach is less clear, maybe because no one yet knows the best way to run these businesses.

Per usual – Agree 100%

It’s yet another example of our tendency to sensationalize concepts that have been at play for centuries. We need people to innovate and break from conformity more than ever – but that doesnt mean you start at innovation and nonconformity (unless your goal is to be featured on Yahoo)

Nice post! It’s funny how many of these stories get distorted to fit the worldview / agenda of a particular group.

Whenever I’ve met the “inspired, brilliant and misunderstood” individual, they’ve been a kook. Being able to pay your dues and work within the system makes it more likely that it’s worthwhile to listen to what you have to say.

Cal, I love this post and at the same time feel completely bitter that I didn’t read it or accept it in my young twenties! The behavior you alluded to – trying to find big shortcuts outside formal schooling – probably set my career back at least 10 years.

Bless you for trying to save others from the same fate.

Im in my mid twenties and this has been one of my favorite blog for the past two years. I guess i can count myself as “saved”.

Thanks Cal. This post is awesome.

Hi Cal,

Love that point about Steve Jobs. He was a fireball at Apple before he got fired, and a lot of people think that his ‘wilderness years’ at NeXT and Pixar were what tempered his fire and enabled him to triumph when he eventually returned.

Not sure if you’ve read it, but Brent Schlender and Rick Tetzeli’s ‘Becoming Steve Jobs’ makes a good case for it. I also wrote a little about his years of failure and eventual comeback here: https://startingmind.com/2015/success-failure-steve-jobs/

Great book.

I don’t buy the Steve Jobs and lucky timing of Apple 2 part. He was a very good salesman from the beginning, even if he was not a good CEO. And even as a CEO he learnt much more about consumer business than the people who worked hard as him because he created NEXT and PIXAR too. He had insight into what people really wanted. Obviously hard work played a role here, but he had tremendous insight generation ability too. We can get a salesman and teach him all about CEO-hood may be, but he wouldn’t be able to do as well as someone who has a natural instinct for impact.

Jobs did not create Pixar. He simply bought it.

It’s sad that obsessive curiosity and devotion to attaining the depth of knowledge + mastery required to truly excel, is considered “conformist” and “inside the box”.

…although if the focused pursuit of excellence was ‘conformist’, seems a lot more people would be doing it, and bloggers like you wouldn’t have to continually emphasize the importance of truly and deeply learning one’s shit. What seems to be happening instead is that many people conflate excellence and achievement with elitism. Elitism has its own box. Excellence and elitism may have a relationship, but they are not the same. Not to mention, the latter never guarantees the former.

This is an interesting angle…

What do you think about the generalized statement that excellence is often conflated with elitism and/or natural brilliance. I see both strains play out, but don’t have a good sense of when one is used versus the other.

I actually think it just comes down to people underestimating the difficulty of originality, and in fact underestimating the strength of other talent out there. I think that summarizes the reasons I thought myself more capable of innovation than I was. I thought other people were relatively inside the box because they were not capable of doing more – not like me. I underestimated the difficulty of even getting into the box in the first place.

Thank you, thank you, thank you! This is a really important point about the balance between “inside the box” and “outside the box” thinking. My mother is really taken with ideas of “unschooling” and trying to push me to do this with my own kids (while I have a full-time job, haha). I’m really struggling with knowing how inadequate and spark-killing traditional schooling can be but also knowing that without it, I could never have gotten to where I am now.

On my path to getting a PhD, I did a lot of coloring inside the lines only to find that this way of doing things can only get you so far when you’re talking about cutting-edge research. But I’ve also seen plenty of “mavericks” in my field who get over-confident in themselves to the point of losing relevance. So… how do you make sure that neither one of these two necessary conditions gets lost along the way?

Have you every read Truth and Beauty by S. Chandrasekhar? I’d be interested to know your thoughts on his discussion of the necessary basis for creativity.

There is no way to share this article through social media plugins.

Your take on The Einstein Myth rings true with everything that I’ve come to understand about the realities of the path to innovating. In particular, one point that you make—In reality, innovation almost always requires long periods of quite traditional training—is dead true!

I’m going to have every friend of mine read this post. Oh, and just to validate that I practice what I preach, having made the preceding comment, I submit this: As a software engineer, I know fully that even the “long periods of quite traditional training” are just the beginning… As practitioners of crafting software, we software types continually update our knowledge—the alternative is obsolescence. To underscore this point, I invite you and the readers of your fine blog to check out a sampling of my posts that take on this very notion.

Cal,

You should check out this link:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vd2dtkMINIw

Some many things to know about how we learn stuff.

Reshmi

Funny thing, Barbara Oakley recommends this blog to the readers of her book.

Great article, Cal. You’ve pointed out an important detail that I wasn’t aware of.

The narrative I’ve been told is quite different: That he was unconventional, therefore nobody offered him a PhD position, so he worked as a patent clerk, where he came up with his brilliant ideas.

But it always struck me as odd how he would learn about the contemporary problems of physics and think about them without being in contact with peers, discussing and reading papers.

Now this whole things makes a lot of sense. Being involved in a research group, even though as patent clerk, provided the context for his enourmous scientific success.

It’s so hard to imagine how to do it in isolation, without contact to peers. One has to associate oneself to highly competent peers to really develop one’s potential, I believe.

It’s like a great basketball player: If he doesn’t play in a top team

This leads me back to Yitang Zhang. He did hold a position as university lecturer, so he also was embedded in an academic context. I wonder whether he worked in isolation or discussed ideas with his peers. My guess would be the latter.

A similar way of telling story like Malcolm Gladwell’s Outlier.

Really enjoyed and excited to see this world from a different lens. Thanks!

Related to the above discussion about whether institutions advance or suppress innovation: Cal, you correctly noted: “In reality, innovation almost always requires long periods of quite traditional training.”

Traditional training usually comes through some sort of institution. The “innovation leader” understands the value and the limitations of an institution. Without these institutions we are unlikely to develop enough creativity to have our creativity suppressed. Without traditional training were unlikely to transcend the limitations of traditional training.

Cal, once again you’ve got that nail and whacked it on the head with your hammer of truth. Is anyone SERIOUSLY surprised that Einstein was a nerd? #cmon

I agree with first post – Before we think out of a box… we must know what is inside a box.

From my own experience, the rigor of higher education is MUST to be successful. I tell my children, if you consider making tons of money or having a fancy title as a success, there are so many means to achieve that. Day traders, street walkers, and preachers make more money than a Sr. scientist makes in Fortune 500 ! Many pan handlers even make more money in India than IT professionals.

Creativity encompasses two things – finding information and putting it to novel use. There are millions of ways these two dots can be connected and how you connect it depends on your training. One can be very good one trick pony by spending 10,000 hours but if you want to be an all rounder…. be like a sponge and keep learning and applying until you drop dead !!

Many of the successful people dropped out of school because they already found what they needed for the next step. They were not “typical dropouts” !! They were brilliant students to begin with.

We live in a culture where our definition of success is teenager’s three base model. Goal should be simple, it should be quick, easy and pleasant enough to give us bragging rights. We have turned traditional education in a joke and we will repent it. Even though I have computers to do the calculations, I know how to them manually because computer can fail. My mind would not.

I agree with the notion that creativity requires years of developing boring hard skills, doing conventional work, and replicating existing work, under the guidance of a good mentor. But the trouble is, Cal, that most of our institutions are not set up to provide this development. Just “doing” your time, even as a grad student, is not enough.

I may be late to the party here but I’ve got a question.

You bring up the Steve Jobs example and for the most part I agree, but was Apple not a multi-billion dollar company even before he was ousted?

Should that awe-worthy accomplishment be overshadowed by his later accomplishments or a foreshadow?

Apple would have been revered as a unicorn before he was kicked out.

Even more some people don’t usually believe in traditional education, its still a good starting point.

There is a fundamental part of everything in life and if you really want to change the world as you quoted, its best you start from inside the box “The fundamental” before stepping outside of it.

Thanks for sharing.

We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.

Of course, he was not boring. He was naturally brilliant.

Einstein also had time. His easy patent office job allowed him to sit and think, and take walks for lunch where he thought about light speed. After he became a working professor he had no time being sucked into the academia trap of writing grant proposals and other endless paperwork and faculty admin duties. True if he wasn’t exposed to the modern research at his study group he would have never had the advanced knowledge to continue further which makes traditional learning an important stepping stone. Too bad it is still very inaccessible for a lot of people.

“The reason I’m telling this story is because it underscores a common habit: we like to cast innovators as outsiders who leverage their freedom from tradition-bound institutions to change the world.

In reality, innovation almost always requires long periods of quite traditional training.”

My thoughts exactly. It is definitely our habit to exaggerate the background of innovators. It just makes them less human. Innovators are human beings too that have undergone traditional training, was aided by knowledgeable teachers (may it be academic or ordinary), and pushed by circumstances that surrounded him.

I don’t want to take anything away from Einstein’s brilliance but he was an immature brat who alienation his professors and was thus blackballed by the Establishment. He had to do some growing up. He refused to call his professor Professor Weber but used the ill-mannered Herr Weber. He didn’t attend physics practicums because he was too busy and too interested in his private research. He had renounced his German citizenship in order to avoid military service – maybe honourable, maybe not.

That said, I am totally in awe of Einstein’s brilliance in physics. How anyone could put together the packages of information and deduce theories of relativity is beyond my comprehension. I’m less enthralled by him as a person

Maybe he wasn’t anything special, just learned to copy, in a job that stopped copies, and went on to be the American con man dream.