Interview: The Late Mary Ellen Mark on Documenting Seattle’s Street Youth

![]()

Documentary photographer Mary Ellen Mark, who has had her photographs featured in publications such as Life, The New Yorker, and Vanity Fair, died yesterday in Manhattan, age 75. She has traveled extensively across the globe, photographing everything from celebrities to Indian circus people.

However, it was a photo essay for Life magazine about kids living in the streets of Seattle which became the foundation for the Academy Award-nominated documentary Streetwise, directed by her husband Martin Bell. Soundtracked by Tom Waits, this film is an intoxicating piece of cinema, a captivating portrait of real-life adolescent teenagers growing up and breaking down.

Jake Sigl of Dazed: A lot of your work is about survival. What draws you to this theme?

Mary Ellen Mark: I’m interested in reality, and I am interested in survival. I’m interested in people who aren’t the lucky ones, who maybe have a tougher time surviving, and telling their story. It’s so changed now from when I started out. I originally did this story for § magazine and it was a time when magazines were interested in documentary photography. Now magazines are interested in Photoshop.

I don’t think it’s digital that’s changed things because I’ve seen some photographers that do beautiful work, digitally. I’m still analog, but I think Photoshop has changed everything. We aren’t looking at reality any more – which is fine – but I think we have to be told we are not looking at reality. People cut off bodies and put on heads and colour things brightly. It’s fine to do that but I think you have to tell the viewer.

At the time I did these pictures everything was real and people loved reality. (Streetwise) is a story about reality, and about kids living on the streets. I remember thinking, “Wow, this would make an amazing film.” Especially when I saw Rat skating down the hallway – that’s so visual you can’t catch that in a picture.

“I’m interested in people who aren’t the lucky ones, who maybe have a tougher time surviving, and telling their story” –Mary Ellen Mark

Why did you want to pursue a documentary about the kids?

Martin Bell: I think the real reason was because Mary Ellen had met these kids, two of them, Tiny and Rat. I was in London at the time. She called me and said, “I met these kids; they’re amazing. They would make a great film.” And she described the actions that she’d seen them in and it sounded great.

What was so engaging about these kids that made you want to photograph them?

Mary Ellen Mark: Well, I have to say it was an assignment. It was an assignment because it was a time when people were actually giving assignments like that. I think that John Leonard was the photo editor at Life magazine then, and he gave me that assignment. The idea was that it was a new phenomenon – the idea of street kids.

They decided to do it in Seattle because it was recently voted America’s most livable city. So they didn’t want to do it in New York or San Francisco because everyone knew that there were a lot of hippies and kids living there. They wanted to pick a city that you wouldn’t expect, and that’s why they picked Seattle.

And you just went to Seattle and started filming?

Martin Bell: Well, what happened first of all was that we needed to raise the money. So Willie Nelson put fifty thousand dollars into the film because Cheryl (McCall), who was a writer for Life magazine, had just worked on a project with him and she was able to bring him to us and he forked over fifty grand. That was pretty amazing. I mean, in 1983 that was a lot of dough. So we went off and made the film.

What were some of the ways that you gained their trust?

Mary Ellen Mark: I was with a writer who was really kind of a hot shot; she was a good journalist. It was lucky in a sense, and also lucky for the film, because there was one centre where the people congregate which was on Pike Street, so we went immediately to Pike Street and I think our greatest breakthrough was Lulu, who made friends with us. She liked us and trusted us, and once she accepted us the kids accepted us. Then, of course, we met Tiny and Rat, and they became the focus of our story.

Martin Bell: On the first day we were shooting at a centre where the kids would hang out during the day. I shot about ten minutes of film and one of the girls who I thought was going to be a character said, “I don’t wanna be in the film.” So I opened the magazine of film, gave her the film, and she just went away. But everybody saw me do that, so in a sense it was like they knew we weren’t going to steal something without them knowing, and that was it. That was it for the ones that were not the main characters, the ones that Mary Ellen had met before.

Did the kids open up to you as you kept filming?

Martin Bell: We didn’t shoot a lot of film. It was 50 hours of film altogether. But every day we’d go down there at the same time and we’d be hanging on the street and something would happen and we would film it and after a while nobody would give a damn. They knew we were making a film; they accepted the fact that they were going to be in this. Also, we had to release them all. Everybody that was in the film was released.

What was the filming process like? Going down there every day, did you follow them around?

Martin Bell: It’s an unusual situation in a sense that it’s all in one place. The majority of the story is one block on Pike Street by the market and we’d just hang there. The reason that the kids came there was because there was a phone booth there. They could make all their phone calls from the street. It was before cell phones.

What were some of the challenges you faced while filming?

Martin Bell: You just have to be there all the time – you can’t ever stop watching or being involved with the kids. It’s like running a marathon, you know? You have to be like a long distance runner I suppose, so it’s physically draining doing that stuff. I think that’s the most challenging thing…and also to get access. That’s probably the most difficult. That is a challenge, and it’s a skill. Cheryl was great at it; Mary Ellen was great at it. They were able to get through doors that normally you wouldn’t be able to get though. So, access and stamina (were required) to keep going.

Were there any times when you were in any danger on the street?

Mary Ellen Mark: No, I’m not a combat photographer. I’ve never been. I tried it once when I was younger and that kind of adrenaline rush wasn’t for me. I didn’t work best under that kind of pressure. It’s not dangerous on the street, especially when you gain people’s trust. You’re aware of what’s around you but it wasn’t particularly dangerous. Get to know people and you get to know whom you can trust and whom you can’t.

“You can try to help, but there’s a line you have to draw about how much you can interfere and when you can interfere. Sometimes you think you’re helping and you’re not, but you know you’re there to observe. You’re there to tell a story” –Mary Ellen Mark

Have you ever felt the need to directly help the kids?

Martin Bell: Well, financially help them – no. You know, if some kids needed shoes or whatever it was – a jacket or something like that – we might do that or, occasionally, food. But the ones that were central to the film we just kept in touch with over time.

Mary Ellen Mark: Sometimes you do feel that need. You can try to help, but there’s a line you have to draw about how much you can interfere and when you can interfere. It’s how far you can go. Sometimes you think you’re helping and you’re not, but you know you’re there to observe. You’re there to tell a story.

Martin Bell: Tiny, for instance, when we left we offered to take her back to New York, to adopt her, essentially. There was a condition to that, and the condition was that she would have to go to school. And she said, “I ain’t going to school.” So she said no. She was very young. She called yesterday, actually. We’ve been following her over the years and we intend to go back this year to follow up. But she said, “I think about it all the time. The fact that I didn’t come.”

Can you tell us more about how you have been revisiting her?

Martin Bell: We went back in 2004 and the early 90s and made a film of her and her family. And we have a film of her already over the years. We have just made a digital transfer of the negative and it’s beautiful actually. It’s amazing. We are going to release it hopefully this year. The follow-up film as well as some other things will be on that when we do the release.

You’ve photographed Tiny’s story throughout the years; have you kept in contact with anybody else?

Mary Ellen Mark: We have. Martin has kept more in contact with people from this story. We’re definitely in contact with Tiny. We’ve been in contact with Shadow, Rat, Kim, of course Lulu died unfortunately. Patti died, too.

Martin Bell: We’re actually going to film with Rat, but it’s amazing now because I haven’t seen him since 1983. I’ve seen photographs of him but it’s amazing because we are different people now.

Can you say what everyone is up to?

Martin Bell: Rat drives break-down trucks. He drives nights on the freeway. You know, if somebody’s car breaks down he goes and hauls them into a garage to be fixed. And he’s got kids; he’s married with kids. Tiny has got ten kids. Shadow is a security guard.

Did you learn anything from the kids?

Mary Ellen Mark: I think you learn from every experience you have. That’s probably why I love working with real people, photographing reality and doing documentary work. I also work for film companies and I do photograph famous people and celebrities. But a major part of my work is doing documentary, or documentary stories based on reality. But you do learn something about humanity. You learn to be more of a human being. To be less judgmental, more open.

Martin Bell: I learned that I am lucky. You have to be born in the right bed, essentially. It’s interesting watching these kids on the street because they’re constantly looking up and down the street, you know? It’s like they’re scanning everything that’s going on. Looking for something, an opportunity. All day long, it’s a full-time job.

Did you come across any problems after the film came out?

Martin Bell: Not really problems. There was one event – the first time we showed the film to anybody, we went back to Seattle and showed it to the kids. And it was in the drop-out centre where the kids would drop in. They all sat on the floor and watched the film. To begin with they were laughing and it was a lot of fun because they were in a movie. Then slowly as the story went on and little themes came out in the film, it got very quiet. And when they saw Dewayne, dead at the end of the film, they were really blown away. Afterwards, when the film finished, one of the teenage boys came up to me and he said, “I’m really angry and I want to hit somebody, but I don’t know who to hit.” But he was just angry about what he witnessed. He was like, “Oh, my god. This is our life.” It’s a realisation of “okay, it was fun for a while and now this is serious business.”

Can you tell us about your next project?

Mary Ellen Mark: Well my next project – actually, our next project, is on prom. We have a book coming out that I did the photos for. We spent four years working on it. Traveling around the country with a huge 20×24 Polaroid Camera. And Martin made a film; it’s going to come with the book.

So this project is domestic based?

Mary Ellen Mark: Yes, it is. I love domestic based stories. It’s something I understand more, and this is about a sort of ritual. We try to look at all aspects of this coming of age ritual, all economic aspects of it. All high schools, from very fancy private high schools to kids who – it’s amazing that they were able to graduate. So it has a full spectrum, which you really see more in the film – a DVD accompanying the book. It’s being published in April.

Has the idea of youth always been a strong concept to you?

Mary Ellen Mark: It’s interesting. I don’t have kids. I never really wanted kids. So it was never even an issue to me to have children. I’ve always been interested in teenagers. When you can really talk to a person, being that age and out there and very raw.

What do you think the film meant to them?

Martin Bell: I don’t know. I don’t know what it means to anybody, actually. You know? I mean, I do know quite often when I see it with an audience—the intensity of the reaction is pretty amazing. People get really involved in the characters, I guess, very strongly. And a few laugh.

About the author: Jake Sigl is a photographer based in New York City who contributes to Dazed, a publication dedicated to youth and pop culture provocateurs since 1991. This interview originally appeared here.

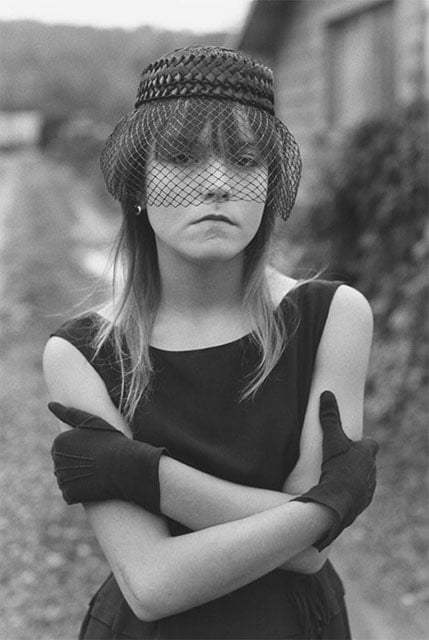

Image credits: Photographs by Mary Ellen Mark