This week’s best city stories from around the web imagine urban neighbourhoods of tree-like houses, explain the existence of ghost cities, look at infrastructure for wildlife and ask whether sending smiley face signals to fellow drivers could cure road rage. We’d love to hear your responses to these stories, and any others you’ve read recently, both on Guardian Cities and elsewhere. Just share your thoughts in the comments below.

Green living

Dutch architect Raimond de Hullu envisages the future of the city ... in the forest. As Fast Co Exist reports, he has designed urban forest neighbourhoods in which there are no cars and where “tree-like” houses are so enveloped in vegetation that they blend into the woodland. His design for a house, OAS1S, runs completely on renewable energy and is made with recycled wood.

De Hullu imagines building these mini-forest neighbourhoods within existing cities, and is look for the first taker. “It will be an exciting and new experience of being in a city as well as being in a forest,” he says. Luxury design gimmick for the rich? De Hullu says no, that he wants to ensure the houses are affordable by using a community land trust model.

Wildlife infrastructure

Oslo recently announced it was creating a “bee highway”: a network of blossoming gardens and shelters designed to protect and sustain the creatures so vital to food production. CityLab have now rounded up other examples of infrastructure around the world that has been created for wildlife. From Canada to the Netherlands, underpasses and overpasses have been built to ensure safe movement of deer, bobcats, bears and other wildlife in places where roads have cut through the landscape.

Ghost cities explained

It is one of the more bizarre stories of urbanism: cities built rapidly for a country undergoing mass urbanisation that end up lying empty, devoid of residents. We’ve explored China’s so-called “ghost” cities before, from Kangbashi to Caofeidian and Tianjin. In CityMetric this week, Wade Shepard notes that these cities in China contain enough empty floorspace to cover the whole of Madrid. He then lists nine explanations for ghost cities – from the lack of services and culture to the phenomenon of houses bought as investments for the future.

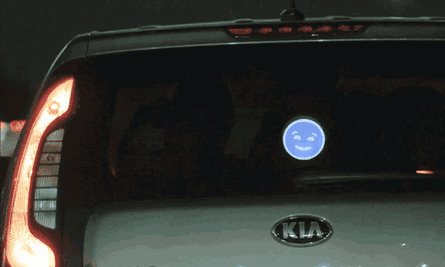

Emojis v road rage

A group of designers in LA have an idea to cut down on road rage: the smiley face. Their gadget MotorMood allows you to light up a smiley face in your rear window to express your thanks to another driver. Essentially, you’re sending them an emoji. As Fast Co Exist reports, the designers argue it enables a positive form of communication while drivers are stuck in traffic, and suggest that a single smiley face could spark a domino effect, helping improve the mood of all drivers in the jam. “We believe positive emotions are contagious,” says inventor Jesse Kramer.

Underneath highways

Gisela Erlacher has been photographing spaces underneath highways and flyovers in China, the UK, the Netherlands and her homeland of Austria. Uncube magazine features a range of her photographs for her most recent project, Skies of Concrete, exploring the uses of leftover spaces below these concrete constructions.

“In Chinese cities you find these kinds of situations in the centre, in European cities they tend to be on the periphery,” she explains. “What is particularly noticeable is that in China it is much more everyday, normal activities and functions: workers’ housing, teahouses and restaurants under bridges are not unusual there. In Europe, in these more peripheral urban situations, most of the structures under bridges are things like facilities for young people such as sports grounds and skate parks, or otherwise parking and storage facilities. What connects all these spaces is the attempt to utilise them.”

Would mini urban forests work in your city? Could emojis really cure road rage? Share your thoughts in the comments below

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion