The information superhighway got diverted last week when a Ukrainian internet service provider hijacked routes used by data heading for websites in the United Kingdom, according to a company that monitors and optimizes internet performance. The action could be a mere glitch—or something more sinister in an era of geopolitical cyber conflicts.

The issue at hand is the way disparate computer networks merge into the internet. The networks announce to one another which internet users—more technically, which IP addresses—they serve so that data can be routed accordingly; a US internet service provider might tell the world it can give you access to the Library of Congress, while one in Germany would say that it can reach BMW’s main website.

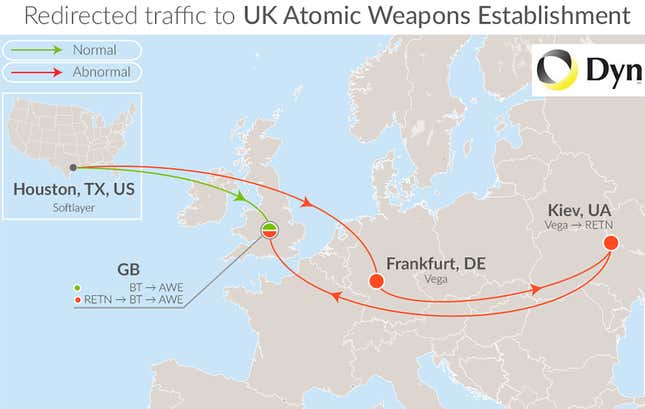

Dyn, the company that noted the incident, keeps an eye on network traffic patterns. Doug Madory, the company’s director of internet analysis, spotted something strange: Vega, a Ukranian internet service provider, had announced it was serving numerous IP addresses in the United Kingdom. Advertising the wrong addresses is called “route hijacking,” and it is often a quickly-corrected mistake—for instance, an employee of an internet service provider makes a typo while typing into a router. In this case, the affected addresses included those operated by defense contractors Lockheed Martin and Thales, the UK Atomic Weapons Establishment, and the Royal Mail.

The effect is a significant share of users trying to reach these sites or send them data from outside the UK were first routed through Kyiv on their way to London:

What does that mean? For starters, it’s not good network management, which is Dyn’s primary interest in the case—it wants companies to buy its services so that their data moves more swiftly through the internet. Vega has a re-selling partnership with UK telecom conglomerate BT, but it’s not clear how that would affect its route announcements; we have asked by both BT and Vega for comment.

But this could also be a security issue. Internet service providers announce the wrong address more often than you think, typically by accident, and the problem is usually corrected fairly quickly. But this route hijacking went on for five days, and could also be a security issue.

Given the growing public knowledge about countries tapping directly into the cables that provide internet service for surveillance purposes, redirecting the traffic through different countries may have exposed the data to monitoring by third parties.

“[The Atomic Weapons Establishment] takes security of all communication very seriously but we do not comment on the measures we have in place,” a spokesperson told Quartz.

“I suspect possibly nobody outside of us noticed that the traffic was going through Kyiv,” Madory told Quartz. “I think people don’t realize how susceptible this system is to manipulation.”

There’s a history of this kind of thing. In 2013, Dyn found a traffic hijacking scheme that directed US internet traffic—”it was clearly directed at US financial institutions,” Madory says—into Belarus, the European dictatorship with close ties to Russia.

In the case of Vega, the company is owned by Rinat Akhmetov, Ukraine’s richest man, with strong ties to Ukraine’s pro-Russian political party. Akhmetov has spoken out against (paywall) the Russian-backed separatists fighting in eastern Ukraine, and was even forced to move his professional soccer team from the region, but at the same time, he has been dogged by accusations that he is funding some of the groups.

But, without knowledge of the data travelling to these websites, Madory can’t say if this is just a weird internet accident or something more troubling. “I can’t see what’s in the pipes, I can just see where the pipes go,” he says.