The First Book of Selfies

A 16th-century German accountant compiled a book of personal fashion that rivals today’s Instagrammers in detail and dedication.

The popularity of YouTube “haul videos,” fashion vlogs, and shoefies is often derided as a sign of the times, if not a sign of the end of times. Combining unbridled narcissism with unabashed materialism, these images—usually self-portraits—rack up millions of hits, and their creators can often become celebrities in their own right. But the impulse to catalogue, classify, and, ultimately, communicate one’s fashion choices is nothing new. Like most everything in fashion, it’s been done before—in Renaissance Germany.

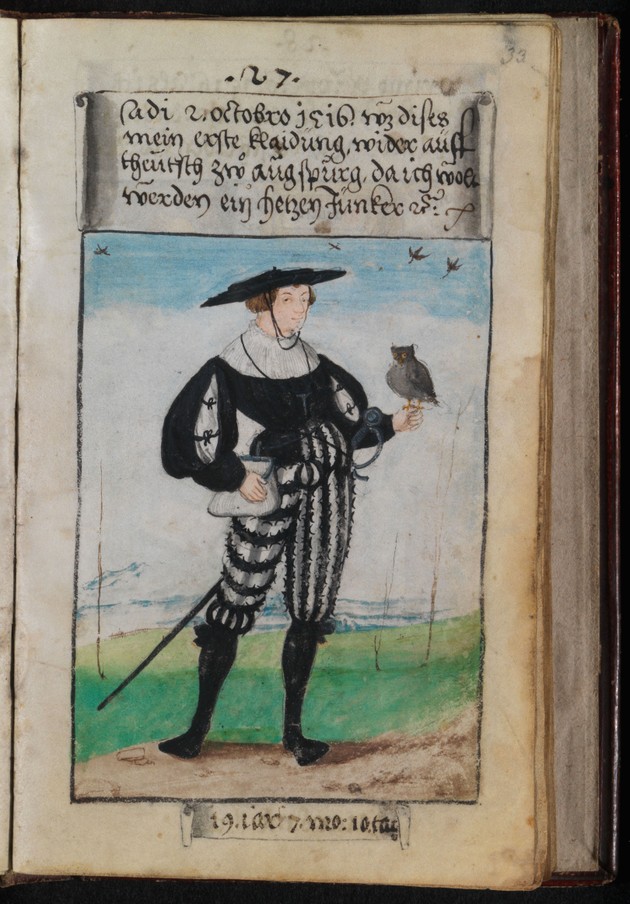

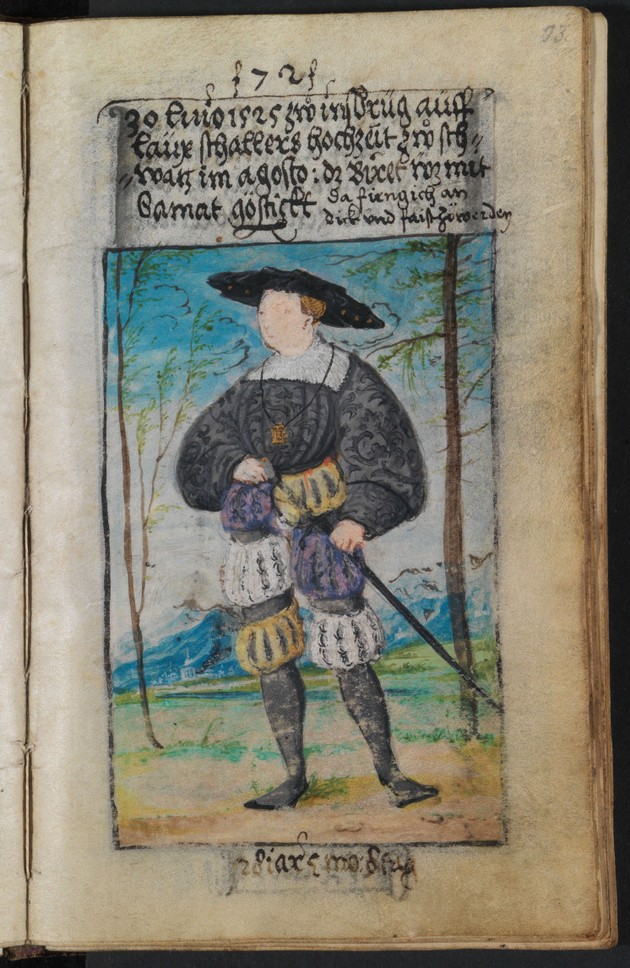

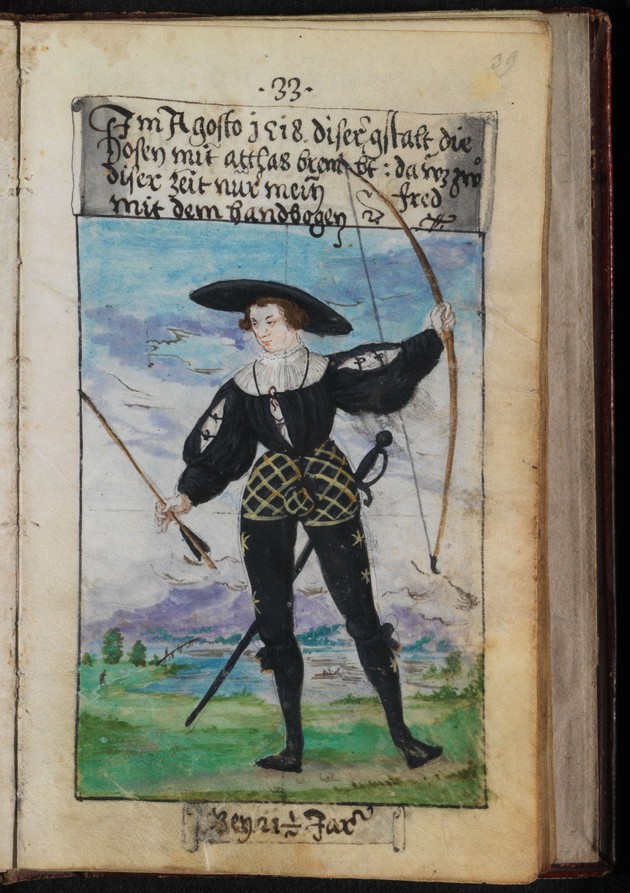

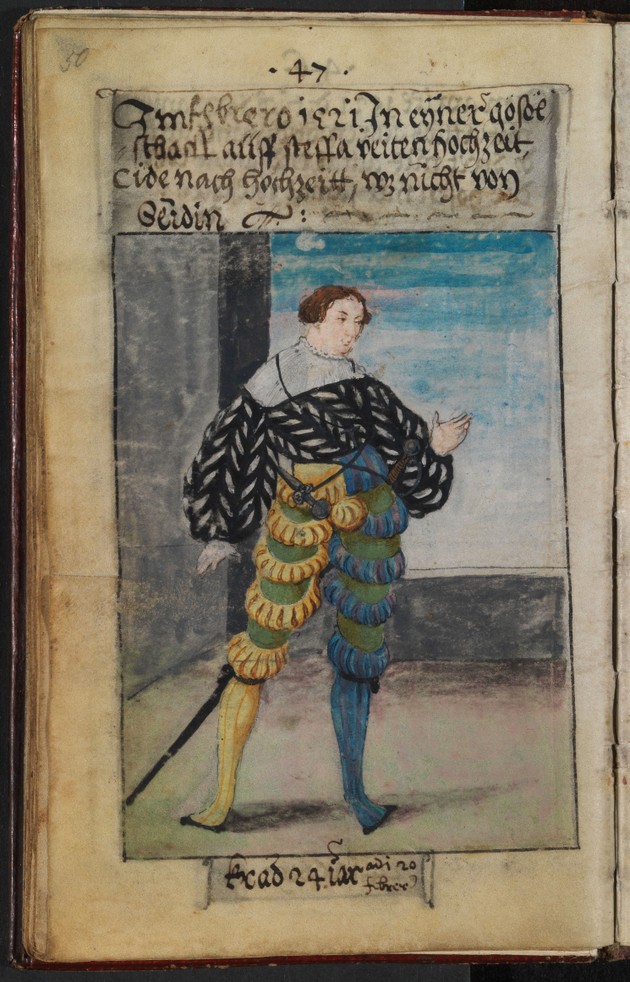

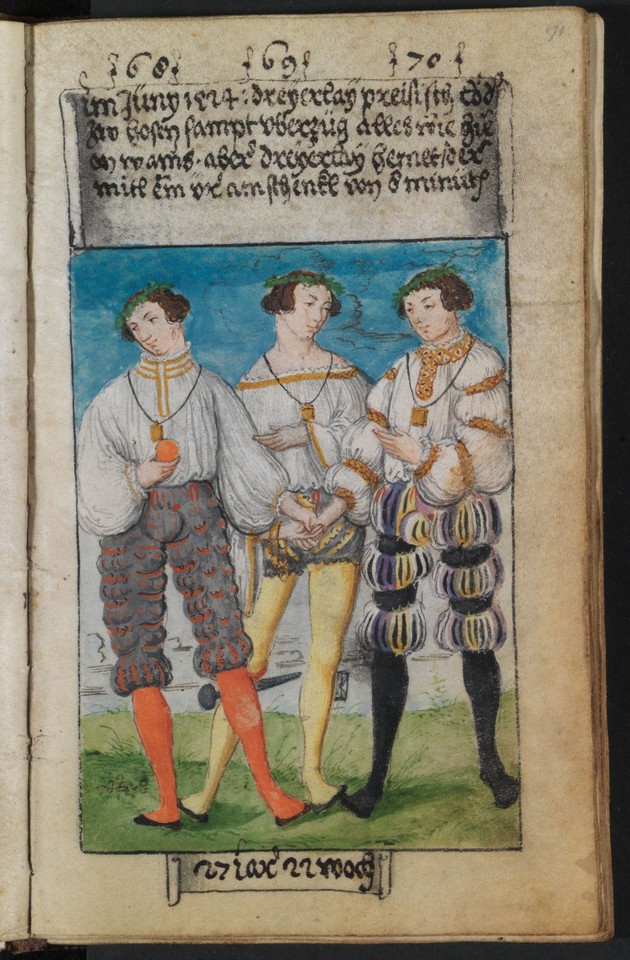

The illuminated Klaidungsbüchlein, or “book of clothes,” compiled by the Augsburg accountant Matthäus Schwarz between 1520 and 1560 is a proto-Kardashian book of selfies. Rendered in rich tempera colors accentuated with costly gilding, the series of hand-drawn portraits meticulously catalogues his extensive and flamboyant wardrobe. The book has been widely known among scholars in Germany since the eighteenth century, but the original manuscript—housed in the Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum in Braunschweig—is so fragile that it’s rarely displayed.

Even the historians Ulinka Rublack and Maria Hayward had to consult it in the company of two curators, who carefully turned the pages for them. Their annotated English translation, The First Book of Fashion, has just been released in both hardback and e-book format, making these 500-year-old images as accessible as The Sartorialist, and just as relevant.

The portraits and their calligraphed captions chronicle the period’s changing male fashions down to the last codpiece, even recording minutiae like the weight of the heavily padded, pumpkin-like nether garments called hose. But they also illustrate how Matthäus advanced politically and socially by carefully managing his image at a time when you were what you wore—much more so than today.

Though remembered for the flowering of humanism and secularism, the Renaissance was still, by modern standards, a repressive era, particularly when it came to clothing. Sumptuary laws regulated which textiles, trimmings, weapons, and even colors could be worn according gender, social class, marital status, and profession. In his 1516 treatise Utopia, Thomas More may have questioned how anyone could “be silly enough to think himself better than other people, because his clothes are made of finer woolen thread than theirs.” But such distinctions were hardwired into Renaissance society.

Within these strictures, however, there was still a broad scope for personal agency. At the time, people effectively designed their own clothes with the help of tailors, dressmakers, and shoemakers. Albrecht Dürer—Matthäus’s contemporary in nearby Nüremberg—left an annotated design for the wide, flat leather shoes popular in the 1520s, and Matthäus boasted of his savvy color and fabric choices as he planned spectacular new outfits for a bewildering variety of occasions, from falcon hunts to funerals. The book raises important questions about the meaning of self-fashioning, now and then.

If 16th-century social hierarchies were more rigid, there was no less emphasis on individualism than among modern Millennials. The Greek philosopher Protagoras, who argued that “man is the measure of all things,” was revered by Renaissance humanists. It was an era of heightened self-awareness, both individual and collective; Matthäus and his contemporaries firmly believed that they were living in a new and more enlightened era of social, intellectual, and religious transformation. Combine this with a growing emphasis on naturalistic observation in the arts and sciences, and you have the perfect climate for epidemic levels of selfie fever.

Fashion was as vital to the Renaissance as painting, architecture, and sculpture, functioning as a visible barometer of unprecedented cultural exchanges and technological advances. The human form was newly prominent in art as well as increasingly visible in mirrors, which encouraged more people to consider what they looked like in the same way that smartphones and social media platforms do today. Augsburg, a city of 30,000, was a cosmopolitan center of politics, finance, and art. The city’s pioneering woodcut printers used multiple blocks and shading effects to create realistic color portraits.

Born in 1497, Matthäus was a member of the burgher (or middle) class. From the age of 23, he kept the books for a man named Fugger the Rich, the head of a famous merchant family whose wealth put them on a par with royalty (they are remembered as “the Medici of the North.”) Almost from his first day on the job, he began work on the Klaidungsbüchlein—an illuminated manuscript consisting of loose pages measuring approximately four by six inches, each bearing a full-length miniature portrait.

The images aren’t selfies in the technical sense; Matthäus was an accountant, not an artist, and he enlisted a succession of four local painters to produce the images (the first died of the plague in 1536). But they are, effectively, self-portraits, and selfies in the spiritual sense: Matthäus chose the costume, postures, details, and backgrounds he wanted included, and even commented on the artists’ work (“The face is well captured.”) In this fashion, he assembled 137 images of himself over 40 years—a selfie record unmatched until the advent of photography.

When Martin Luther complained that Germans spent too much money on imported luxury goods, he may well have been thinking of Matthäus, who often noted the cost of his garments and seems to have taken pride in recording tailoring bills in excess of the materials, a new and important benchmark of luxury at the time. Matthäus never met a Spanish cape or Siberian squirrel-fur lining he didn’t like. The book depicts suits of armor, embroidered shirts, reversible garments, and hose trimmed with fringe, ornamental metal aglets, or little bells. Such was Matthäus’s addiction to colorful headgear that male friends sometimes gave him caps as gifts, which were then depicted and described in breathless detail in the book. (One, he notes sadly, was later “pushed into some cow dung. It was useless.”)

Though Matthäus’s wardrobe seems to have been typical for his time and place, that milieu occupies a rather unique niche in fashion history. With its thriving textile and metalwork industries and its proximity to Italy, Augsburg was, for a brief period between the late 15th century and the Reformation, home to some of the most elaborate male fashions ever worn. The book is bursting with color, asymmetry, stripes, and decorative paning, pinking, and slashing; one especially fabulous white doublet is slashed 4,800 times. The period saw the development of specialist sportswear for fencing, archery, and sledding—activities that required leisure time and permitted social networking. The Klaidungsbüchlein depicts these over-the-top fashions much more precisely and clearly than even Augsburg’s own Hans Holbein, who was one of the century’s greatest portraitists.

But fashion wasn’t just an idle pastime or foppish indulgence. It conveyed a multitude of messages, from the financial to the political. Since part of the Fugger merchant empire involved the international textile trade, Matthäus may have boosted his career by advertising the company’s wares. He often strategically selected his outfits to appeal to visiting politicians, wearing the French colors of yellow and blue to welcome King Francis I to Milan, and even commissioning six new outfits to impress Emperor Charles V and King Ferdinand into awarding him a noble title when they visited for the Diet of Augsburg.

As they do today, appearances played an important role in courtship as well. As a young man looking for a wife in a city overrun with young, unmarried male apprentices and journeymen, Matthäus carried heart-shaped purses in green and red—the colors of hope and desire. He captioned one splendid outfit: “All of this to please a beautiful person.” Following fashion also provided a hobby for all those lonely young men, who generally married late, once they had finished their vocational training, and thus had leisure time, money, and energy to expend on dressing up. It’s no coincidence that “urban young men” were the “drivers of innovative Renaissance fashion,” as Rublack points out. Several of the images in the book record what Matthaüs wore to the weddings of close friends (often matching his attire to that of other members of the bridal party) during his long bachelorhood.

The Klaidungsbüchlein effectively documents most of the rest of Matthaüs’s life. After he got married, his whole wardrobe faded to blacks and browns, and the gaps between images became longer. He grew a beard—a sign of maturity and masculinity—and traded his ornate, form-fitting doublets and hose for long, formal, fur-lined gowns. “This is when I began to be fat and round,” he notes despondently. Then in 1547, he suffered a stroke (“God’s mightiness hit me”), and managed to commission a portrait during his convalescence. Today, this rare Renaissance depiction of an invalid is one of the best known images in the Klaidungsbüchlein. But this is one of the last entries in the book. In the final image, he is a gray-bearded old man, dressed in mourning for his employer’s 1560 funeral. It might as well have been his own funeral: Matthäus lived another 14 years without commissioning a single portrait.

Matthäus’s preoccupation with fashion had always gone hand in hand with a keen sense of temporality and, by extension, mortality. Like his expanding waistline or recurring birthday—both of which he tracked with obsessive and, for his time, unusual assiduity—fashion, which seemed to change “day-by-day,” was a marker of the passage of time; “a vanishing moment of creativity and pleasure,” in Rublack’s phrase. One portrait depicts him with an eight-minute hourglass hanging from his belt. Another jaunty outfit is captioned: “On the 20th August, 1535, when people in Augsburg began to die. 38½ years old.”

But the self-documenting didn’t stop there. Concerned about his legacy, Matthäus pressured his second son, Veit Konrad Schwarz, to continue the family tradition and compile his own Klaidungsbüchlein. Larger in format and smaller in scope, Veit Konrad’s book includes 41 images covering the years 1540 to 1561, but his heart wasn’t in it. His prologue declared that fashion and his father were foolish, and he stopped adding to the book when Matthäus abandoned his. It may have been a classic generational difference, but the portraits of Veit Konrad—reproduced in the new edition—suggest a simpler explanation: Fashion just wasn’t much fun anymore. Matthäus’s son wore little fur, preferred a more subdued color palette, in line with Protestant sobriety, and growing nationalism and trade protectionism tempered the international flavor of Augsburg style.

Rublack suggests another possibility: that Matthäus’s efforts to make sense of his turbulent times had backfired. “Alarmingly, much of what had been valued in the past could seem misguided and hence suggested that all culture, including art, was a succession of styles that perhaps neither increased sophistication nor achieved timeless beauty,” she writes. “Fashion made the past and present look arbitrary rather than presenting a linear story of progress.” Matthäus may have come to realize that his strenuous efforts to manufacture and control and refine his public image proved less durable than he’d hoped. Rather than bringing order to chaos, his highly personal sartorial narratives only underscore fashion’s elusive and capricious nature.

If The First Book of Fashion is unlikely to propel the Schwarzes to celebrity status, it will reach a wider audience than Matthäus and his son ever dreamed. And it may even prompt readers to reconsider Millennials—with their solipsism and pics-or-it-didn’t-happen visual acuity—as the harbingers of a second Renaissance. While avid shopping vloggers and Instagram-style celebrities may continue to face some degree of scorn, The First Book of Fashion serves as a reminder that, like other forms of culture, fashion is a product of its time. And it’s precisely because true permanence is impossible that clothing choices and self-documentation can offer such rich insight into the values of the past.