For the past three years or so, at least one stranger has sought me out pretty much every day to call me a fat bitch (or some pithy variation thereof). I’m a writer and a woman and a feminist, and I write about big, fat, bitchy things that make people uncomfortable. And because I choose to do that as a career, I’m told, a constant barrage of abuse is just part of my job. Shrug. Nothing we can do. I’m asking for it, apparently.

Being harassed on the internet is such a normal, common part of my life that I’m always surprised when other people find it surprising. You’re telling me you don’t have hundreds of men popping into your cubicle in the accounting department of your mid-sized, regional dry-goods distributor to inform you that – hmm – you’re too fat to rape, but perhaps they’ll saw you up with an electric knife? No? Just me? People who don’t spend much time on the internet are invariably shocked to discover the barbarism – the eager abandonment of the social contract – that so many of us face simply for doing our jobs.

Sometimes the hate trickles in slowly, just one or two messages a day. But other times, when I’ve written something particularly controversial (ie feminist) – like, say, my critique of men feeling entitled to women’s time and attention, or literally anything about rape – the harassment comes in a deluge. It floods my Twitter feed, my Facebook page, my email, so fast that I can’t even keep up (not that I want to).

It was in the middle of one of these deluges two summers ago when my dead father contacted me on Twitter.

At the time, I’d been writing a lot about the problem of misogyny (specifically jokes about rape) in the comedy world. My central point – which has been gleefully misconstrued as “pro-censorship” ever since – was that what we say affects the world we live in, that words are both a reflection of and a catalyst for the way our society operates. When you talk about rape, I said, you get to decide where you aim: are you making fun of rapists? Or their victims? Are you making the world better? Or worse? It’s not about censorship, it’s not about obligation, it’s not about forcibly limiting anyone’s speech – it’s about choice. Who are you? Choose.

The backlash from comedy fans was immediate and intense: “That broad doesn’t have to worry about rape.” “She won’t ever have to worry about rape.” “No one would want to rape that fat, disgusting mess.” “Holes like this make me want to commit rape out of anger.” It went on and on, to the point that it was almost white noise. After a week or so, I was feeling weather-beaten but fortified. Nothing could touch me anymore.

But then there was my dad’s dear face twinkling out at me from my Twitter feed. Someone – bored, apparently, with the usual angles of harassment – had made a fake Twitter account purporting to be my dead dad, featuring a stolen, beloved photo of him, for no reason other than to hurt me. The name on the account was “PawWestDonezo”, because my father’s name was Paul West, and a difficult battle with prostate cancer had rendered him “donezo” (goofy slang for “done”) just 18 months earlier. “Embarrassed father of an idiot,” the bio read. “Other two kids are fine, though.” His location was “Dirt hole in Seattle”.

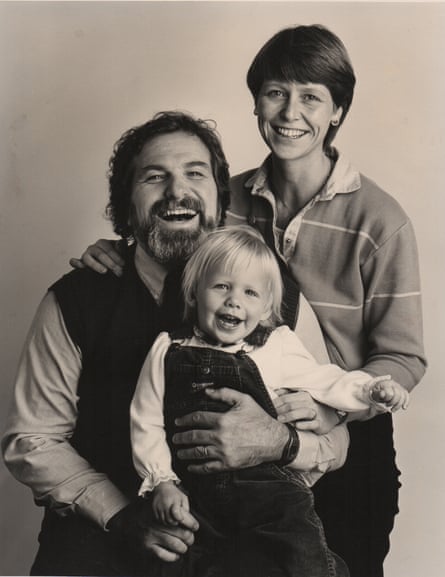

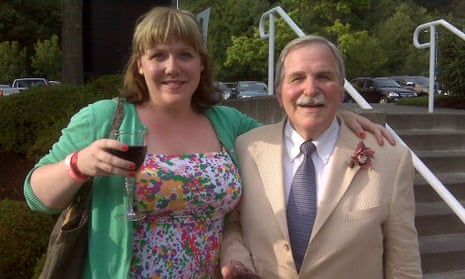

My dad was special. The only thing he valued more than wit was kindness. He was a writer and an ad man and a magnificent baritone (he could write you a jingle and record it on the same day) – a lost breed of lounge pianist who skipped dizzyingly from jazz standards to Flanders and Swann to Lord Buckley and back again – and I can genuinely say that I’ve never met anyone else so universally beloved, nor do I expect to again. I loved him so, so much.

There’s a term for this brand of gratuitous online cruelty: we call it internet trolling. Trolling is recreational abuse – usually anonymous – intended to waste the subject’s time or get a rise out of them or frustrate or frighten them into silence. Sometimes it’s relatively innocuous (like asking contrarian questions just to start an argument) or juvenile (like making fun of my weight or my intelligence), but – particularly when the subject is a young woman – it frequently crosses the line into bona fide, dangerous stalking and harassment.

And even “innocuous” harassment, when it’s coming at you en masse from hundreds or even thousands of users a day, stops feeling innocuous very quickly. It’s a silencing tactic. The message is: you are outnumbered. The message is: we’ll stop when you’re gone. The volume and intensity of harassment is vastly magnified for women of colour and trans women and disabled women and fat women and sex workers and other intersecting identities. Who gets trolled has a direct impact on who gets to talk; in my personal experience, the fiercest trolling has come from traditionally white, male-dominated communities (comedy, video games, atheism) whose members would like to keep it that way.

I feel the pull all the time: I should change careers; I should shut down my social media; maybe I can get a job in print somewhere; it’s just too exhausting. I hear the same refrains from my colleagues. Sure, we’ve all built up significant armour at this point, but, you know, armour is heavy. Internet trolling might seem like an issue that only affects a certain subset of people, but that’s only true if you believe that living in a world devoid of diverse voices – public discourse shaped primarily by white, heterosexual, able-bodied men – wouldn’t profoundly affect your life.

Sitting at my computer, staring at PawWestDonezo, I had precious few options. All I could do, really, was ignore it: hit “block” and move on, knowing that that account was still out there, hidden behind a few gossamer lines of code, still putting words in my dad’s mouth, still using his image to mock, abuse and silence people. After all, it’s not illegal to reach elbow-deep into someone’s memories and touch them and twist them and weaponise them (to impress the ghost of Lenny Bruce or whatever). Nor should it be, of course. But that doesn’t mean we have to tolerate it without dissent.

Over and over, those of us who work on the internet are told, “Don’t feed the trolls. Don’t talk back. It’s what they want.” But is that true? Does ignoring trolls actually stop trolling? Can somebody show me concrete numbers on that? Anecdotally, I’ve ignored far more trolls than I’ve “fed”, and my inbox hasn’t become any quieter. When I speak my mind and receive a howling hurricane of abuse in return, it doesn’t feel like a plea for my attention – it feels like a demand for my silence.

And some trolls are explicit about it. “If you can’t handle it, get off the internet.” That’s a persistent refrain my colleagues and I hear when we confront our harassers. But why? Why don’t YOU get off the internet? Why should I have to rearrange my life – and change careers, essentially – because you wet your pants every time a woman talks?

My friends say, “Just don’t read the comments.” But just the other day, for instance, I got a tweet that said, “May your bloodied head rest on the edge of an Isis blade.” Colleagues and friends of mine have had their phone numbers and addresses published online (a harassment tactic known as “doxing”) and had trolls show up at their public events or threaten mass shootings. So if we don’t keep an eye on what people are saying, how do we know when a line has been crossed and law enforcement should be involved? (Not that the police have any clue how to deal with online harassment anyway – or much interest in trying.)

Social media companies say, “Just report any abuse and move on. We’re handling it.” So I do that. But reporting abuse is a tedious, labour-intensive process that can eat up half my working day. In any case, most of my reports are rejected. And once any troll is blocked (or even if they’re suspended), they can just make a new account and start all over again.

I’m aware that Twitter is well within its rights to let its platform be used as a vehicle for sexist and racist harassment. But, as a private company – just like a comedian mulling over a rape joke, or a troll looking for a target for his anger – it could choose not to. As a collective of human beings, it could choose to be better.

So, when it came to the case of PawWestDonezo, I went off script: I stopped obsessing over what he wanted and just did what felt best to me that day. I wrote about it publicly, online. I made myself vulnerable. I didn’t hide the fact it hurt. The next morning, I woke up to an email:

Hey Lindy, I don’t know why or even when I started trolling you. It wasn’t because of your stance on rape jokes. I don’t find them funny either.

I think my anger towards you stems from your happiness with your own being. It offended me because it served to highlight my unhappiness with my own self.

I have e-mailed you through 2 other gmail accounts just to send you idiotic insults.

I apologize for that.

I created the PaulWestDunzo@gmail.com account & Twitter account. (I have deleted both.)

I can’t say sorry enough.

It was the lowest thing I had ever done. When you included it in your latest Jezebel article it finally hit me. There is a living, breathing human being who is reading this shit. I am attacking someone who never harmed me in any way. And for no reason whatsoever.

I’m done being a troll.

Again I apologize.

I made donation in memory to your dad.

I wish you the best.

He had donated $50 to Seattle Cancer Care Alliance, where my dad was treated.

That email still unhinges my jaw every time I read it. A reformed troll? An admission of weakness and self-loathing? An apology? I wrote back once, expressed my disbelief and said thank you – and that was that. I returned to my regular routine of daily hate mail, scrolling through the same options over and over – Ignore? Block? Report? Engage? – but every time I faced that choice, I thought briefly of my remorseful troll.

Last summer, when a segment of video game fans began a massive harassment campaign against female critics and developers (if you want to know more, Google “GamerGate”, then shut your laptop and throw it into the sea), my thoughts wandered back to him more and more. I wondered if I could learn anything from him. And then it struck me: why not find out?

We only had made that one, brief exchange, in the summer of 2013, but I still had his email address. I asked the popular US radio programme This American Life to help me reach out to him. They said yes. They emailed him. After a few months of gruelling silence, he finally wrote back. “I’d be happy to help you out in any way possible,” he said.

And then, there I was in a studio with a phone – and the troll on the other end.

We talked for two-and-a-half hours. He was shockingly self-aware. He told me that he didn’t hate me because of rape jokes – the timing was just a coincidence – he hated me because, to put it simply, I don’t hate myself. Hearing him explain his choices in his own words, in his own voice, was heartbreaking and fascinating. He said that, at the time, he felt fat, unloved, “passionless” and purposeless. For some reason, he found it “easy” to take that out on women online.

I asked why. What made women easy targets? Why was it so satisfying to hurt us? Why didn’t he automatically see us as human beings? For all his self-reflection, that’s the one thing he never managed to articulate – how anger at one woman translated into hatred of women in general. Why, when men hate themselves, it’s women who take the beatings.

But he did explain how he changed. He started taking care of his health, he found a new girlfriend and, most importantly, he went back to school to become a teacher. He told me – in all seriousness – that, as a volunteer at a school, he just gets so many hugs now. “Seeing how their feelings get hurt by their peers,” he said, “on purpose or not, it derails them for the rest of the day. They’ll have their head on their desk and refuse to talk. As I’m watching this happen, I can’t help but think about the feelings that I hurt.” He was so sorry, he said.

I didn’t mean to forgive him, but I did.

This story isn’t prescriptive. It doesn’t mean that anyone is obliged to forgive people who abuse them, or even that I plan on being cordial and compassionate to every teenage boy who tells me I’m too fat to get raped (sorry in advance, boys: I still bite). But, for me, it’s changed the timbre of my online interactions – with, for instance, the guy who responded to my radio story by calling my dad a “faggot”. It’s hard to feel hurt or frightened when you’re flooded with pity. And that, in turn, has made it easier for me to keep talking in the face of a mob roaring for my silence. Keep screaming, trolls. I see you.

Hear Lindy West’s show at This American Life

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion