Working hard, hardly working

Our obsession with putting in long hours on the job doesn’t mean we’re actually getting much done

Share

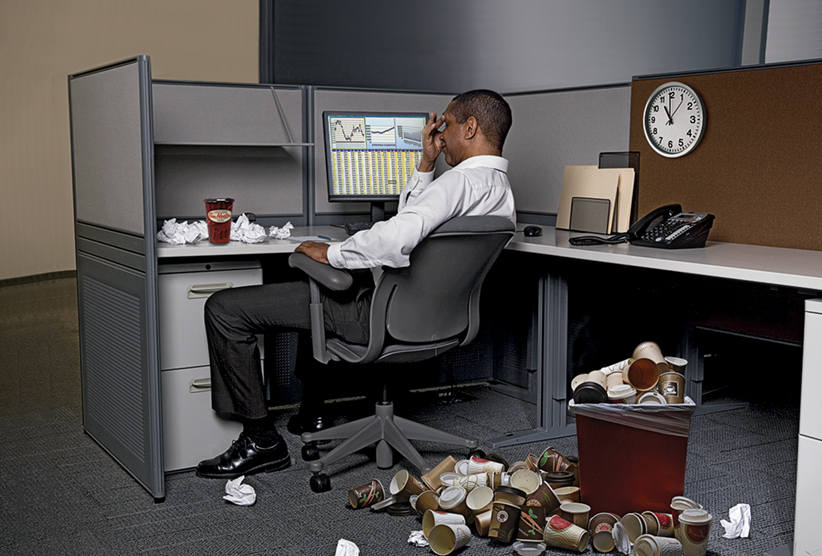

Canadians see themselves as a hard-working bunch. We spend long hours at the office, eat at our desks and guzzle as many Tim Hortons “double-doubles” as needed to get through a workday that, thanks to smartphones, no longer really begins or ends. Even when it comes time to take a hard-earned vacation, we’re reluctant to go idle: a TD study last year discovered that less than half of Canadian workers use all their paid days off, while a more recent study by human resources consulting firm Randstad found that 40 per cent of Canadians didn’t mind working while on holidays.

It would be an impressive and industrious, if slightly dull, approach to life were it not for one nagging detail: we don’t get much done. Canada’s productivity—the total amount of economic output divided by the total amount of hours worked–lags most other developed countries, according to figures from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). That includes those nations we enjoy making fun of for their famously carefree approach—namely France.

And yet, when faced with a persistent productivity gap, Canadian politicians have mostly ignored the issue or implied, as Prime Minister Stephen Harper did in a pre-election campaign ad, that the country’s myriad woes can be solved by staying at the office long after the sun goes down. But study after study has shown that, after a certain point (around 50 hours a week), there’s little benefit to spending more time at work, and it may in fact be counterproductive, a reality recognized nearly a century ago by Henry Ford when he slashed his employees’ workweek to 40 hours in a bid to build more Model Ts.

So why do we persist in trying to work longer hours to less effect? Researchers call the trend “perceived productivity” and blame it on everything from the nature of work in a modern economy to the increasingly precarious nature of jobs themselves. The current obsession with technology companies like Apple, Google and Facebook also plays a role, helping to popularize the idea that work and play can comfortably co-exist in a 24-7 office equipped with Ping-Pong tables, nap rooms and free gourmet meals.

But the downsides are potentially huge, ranging from bleary-eyed workers who make frequent mistakes, to a persistent pay gap for women in the workplace. Breaking out of the cycle isn’t easy, or straightforward. But Canada, for one, may ultimately find it has little choice. The economy, having slipped into recession earlier this year, remains precarious. Getting back on track means figuring out ways to squeeze more actual work out of each hour, which, in addition to the usual calls for more corporate investment in labour-saving technology and equipment, may ironically mean devoting fewer hours to your job.

Like most hungry entrepreneurs, Katie Fang didn’t realize that her grinding work schedule was holding her back. The recent graduate of the University of British Columbia’s Sauder School of Business spent a year-and-a-half struggling to get SchooLinks, an online platform to connect students with foreign schools and recruiters, off the ground. Fang found herself working six or seven days a week and pulling frequent all-nighters–anything to improve the Austin, Tex.-based company’s chances of making money. A low point came during a recent 2 a.m. taco run with her six-member team of sleep-deprived coders. “I backed my car into a pole,” Fang says.

The warning signs had been there all along, of course. Fang, 24, and her colleagues had been nodding off at work while their coffee consumption spiked. More importantly, she noticed her employees were getting less work done. “I saw that we were burning out, including myself,” she says. “Our productivity had dropped. You can see where things are slowing down because [in software development] everything can be tracked.”

Fang’s realization shouldn’t have come as a surprise. There’s plenty of research demonstrating the limits of human endurance when it comes to work. British economist John Hicks reasoned back in the 1930s that longer hours would negatively impact productivity as employees become tired and lose focus. Stanford University economics professor John Pencavel re-tested the theory in a paper last year that looked at data originally collected on munitions factory workers in England during the First World War. Now, as then, the conclusion was the same: workers’ productivity begins to decline after 49 hours a week, and that working more than 70 hours a week is essentially a waste of time.

Other studies have found that the most productive employees frequently work less than eight hours a day, taking frequent breaks, and that the best musicians practice less than their peers and take extended rest periods. “There’s strong evidence that disengagement, breaking away, can help recharge people cognitively,” says University of Toronto sociology professor Scott Schieman. ![]() [tweet this] Schieman is studying the relationship between work, health and stress among Canadians. “This is anecdotal, but if I’ve gone on vacation and I come back, the ideas flow and things really move along. By contrast, if I’m sitting at my desk trying to squeeze out the last bit of idea, it just doesn’t work.”

[tweet this] Schieman is studying the relationship between work, health and stress among Canadians. “This is anecdotal, but if I’ve gone on vacation and I come back, the ideas flow and things really move along. By contrast, if I’m sitting at my desk trying to squeeze out the last bit of idea, it just doesn’t work.”

The notion that the most productive employees aren’t necessarily the ones who work all the time helps explain France’s surprisingly efficient workforce, which, despite enjoying an average of 30 vacation days a year, still manages to produce about $63 (U.S.) worth of national GDP per capita, per hour, well above the OECD average. Canadian workers, by contrast, devote among the least number of hours per week in the OECD to leisure activities, but only manage to produce about $51 worth of GDP per hour worked. Even Italy fares better. (There are, however, some who argue Canada’s poor productivity numbers are skewed by our large resource sector: when oil prices are high, for example, there’s less pressure to relentlessly drive down costs and boost productivity to make money. That may be among the reasons Canada still manages to be a relatively prosperous country, although the recent rout in global commodities prices could put this hypothesis to the test).

It’s not just a Canadian problem. Employees in the notoriously workaholic U.S., where there’s no mandated paid vacation, sick days or maternity leave, are also seeing their famous productivity slip, threatening to hold back the country’s economic recovery. While Americans work some of the longest hours in the developed world, productivity is up by just 1.3 per cent over the past eight years, less than half the rate of the past half-century. What the numbers don’t capture is just how miserable some American workers have become, with eight out of 10 saying they feel stressed about some aspect of their job, according to a 2014 poll by Nielsen. No wonder critics jumped on Republican U.S. presidential hopeful Jeb Bush when he suggested Americans “need to work longer hours” to power the country’s economic recovery.

The potential human cost of overwork recently made headlines when the New York Times wrote about Amazon’s “bruising” workplace culture. The newspaper suggested the online retailer was on the vanguard of figuring out new ways to drive its 154,000 employees harder and longer, leaving many of them sobbing in the conference rooms of its Seattle headquarters. Among the complaints: emails that arrive past midnight with the expectation of a prompt response, internal systems that can be used to rat out employees who aren’t pulling their weight, and an annual culling of staff that was described as “purposeful Darwinism.” While CEO Jeff Bezos said the “soulless, dystopian workplace” described by the Times didn’t sound like the Amazon he knows, it’s hardly the first time the company has been singled out for its workplace practices. Amazon fought and won a U.S. Supreme Court case over its policy not to pay employees for time spent waiting in security screening lines (to make sure they haven’t stolen anything from Amazon’s warehouses) following their shifts. During a heat wave in Pennsylvania several years ago, Amazon hired ambulances to be stationed outside its warehouses to whisk away workers who succumbed to heat exhaustion instead of simply sending them home, according to a local newspaper.

How we got into this mess is anything but clear. Some blame the lingering impact of the Great Recession, which prompted employers across North America to cut to the bone and made employees everywhere fear for their jobs. “When there’s economic downturns, and job security decreases, people want to be seen as the ideal worker,” Schieman says. “Anything that signals to employers that you’re not fully on board could maybe get you into trouble when times are tight.” At the same time, technological advances like email-equipped BlackBerrys and iPhones have provided both hard-driving employers and eager-to-please employees with the necessary tools to realize something approximating a perpetual workday.

But if tough economic times exacerbated North America’s culture of overwork, they did not create it. The underlying issue, experts say, is the slow march toward a “knowledge economy,” where designers and consultants replace labourers and factory workers. Put another way: while it was relatively straightforward for British officials to see the relationship between employee hours worked and the number of bombs that rolled off the assembly line, it’s not nearly as easy to measure how many positive vibes a director of public relations produces for a big insurance firm. The same goes, to varying degrees, for architects, software engineers and financiers. And so, at many companies, “work hours get used as a proxy measure for productivity,” says Youngjoo Cha, an assistant professor of sociology at Indiana University, who has studied the overwork phenomenon. “But research suggests that time is not a good predictor of how productive workers are. A lot of people spend a lot of hours at work, but aren’t necessarily working a lot of hours.” ![]() [tweet this]

[tweet this]

This will come as no surprise to anyone who has worked in a modern office. Most employees begin the day by responding to a flood of emails before heading off to a series of meetings that must be prepared for and followed up on later. Next, it’s lunch, more meetings and a few unannounced visits from co-workers who stop by to chat. “You walk into the front door and it’s like a Cuisinart,” Jason Fried, a co-founder of Basecamp, which makes web-based workplace collaboration tools, said during a 2010 TED talk that’s received nearly four million online views. “Your day is just shredded to bits.” The constant stream of interruptions makes it difficult to accomplish relatively simple tasks—never mind employing the sort of unbroken concentration needed to solve complex problems. Some liken the experience to having one’s sleep constantly interrupted before they reach the all-important REM stage, leaving them feeling fatigued and frazzled with little to show for their efforts.

Email, in particular, is a source of frustration. While normally seen as an efficient communication tool, Schieman says in reality many managers’ emails are loaded with layered sets of demands, unclear expectations and passive-aggressive tone. That, in turn, forces workers to waste time deciphering them and crafting suitable responses—even late at night. Says Schieman, “I’ve had instances where people send email at 10:45 p.m. and if I don’t respond until the next morning, sometimes I get a little bit of flak for it.”

And yet, despite the mounting evidence that the office is a poor place to get actual work done, racking up long hours under fluorescent lights has emerged as a badge of honour in North American business culture. A recent study by Erin Reid, an assistant professor at Boston University’s business school, found that one large U.S. consulting firm rewarded employees who worked 80-hour weeks and travelled at the drop of a hat with higher salaries and promotions, whereas employees who asked for more manageable, part-time schedules were marginalized. While that might sound reasonable on the face of it—employees who work more, deserve more—the same study also showed that workers who merely pretended to be among the firm’s “superheroes” received the professional and compensation benefits despite putting in far fewer hours. A Seinfeld episode comes to mind: the one where George leaves his car parked at the New York Yankees’ head office overnight, creating the impression he’s the first in and last to leave, and is put in line for a promotion.

Cha calls the phenomenon “perceived productivity,” or the notion that “so-and-so must be fantastic because he’s working all the time, and is always on call.” Her research found that people who fall into that category by working more than 50 hours a week are paid up to seven per cent more than people who don’t, with the gap even wider among professionals and managers. She argues it’s a major reason why women continue to be disadvantaged in the workplace when it comes to pay and promotions, despite having closed the gap in other areas likes education. “If you think about who workers are, these people who can actually work all the time, as if they have no other life”—or can at least pretend like that’s the case—“they’re male workers in a traditional family arrangement with a stay-at-home wife who can take care of the children and other family members.”

Nor does it help that many of America’s corporate heroes—mostly male and mainly in tech—are proud workaholics. The late Apple co-founder Steve Jobs would call people at all hours, take business meetings at home and, by all accounts, worked right up until the day he died of complications from cancer in 2011. His successor, Tim Cook, isn’t much better. He reportedly begins sending emails at 4:30 a.m. and held staff meetings on Sunday nights to get a jump on the workweek. Similarly, billionaire Dallas Mavericks owner Mark Cuban has boasted about how he didn’t take a vacation for seven years while starting his first software company.

Back in Austin, Fang says she, too, got caught up in Silicon Valley’s mantra of “all work, no play.” But after recognizing that her startup was suffering, she limited her staff to a four-day workweek. The results were unexpected, but shouldn’t have been surprising. “So far, I would say the results have been great,” she says. “I’ve seen a boost in productivity.” An added bonus: Many of her young team members are using the extra day off to read about programming or work on side projects, which inevitably helps build skills and, indirectly, benefits the company.

Other firms are making changes, too. Another small tech company in Portland, Treehouse, has also adopted a four-day week for productivity reasons, while consulting giant KPMG made 32-hour weeks a regular option for employees after first introducing the idea as a cost-cutting measure. Even Goldman Sachs, the Wall Street investment bank, recently told its summer interns not to come into the office between midnight and 7 a.m., after a 22-year-old analyst was found dead in the parking lot outside his San Francisco apartment building. He had committed suicide after complaining about the bank’s long hours and pressure-cooker culture.

However, the trend is not to be confused with one that’s seen employers granting all manner of perks in the name of “work-life balance.” Google’s headquarters, for example, has nap pods and free gourmet meals. Facebook’s new campus boasts a barbershop. In Canada, Chubb Insurance Co. touts an in-house yoga studio, while FlightCentre held a global employee event in Macau that featured singers Will.i.am and Jessie J. Experts caution that such freebies risk exacerbating the overwork problem by giving employees more reasons to stay at the office. In fact, Cha says it’s often the companies touted as being the most progressive in this area, including the ones that ostensibly offer “flexible” work-from-home schedules, that have the most overworked employees. “The overwork culture is so prevalent it actually hinders workers from taking advantage of the work-life balance policies available to them,” Cha says. “That’s the most depressing thing about this overwork problem. It’s so built into people’s psyche that it’s hard to take it apart.”

Meanwhile, at the other end of the spectrum, is Amazon. The Times said the company was one of several leading the charge toward a data-driven workplace designed to systematically suck every last bit of output from employees. And while it might be tempting to assume the hard-driving attitude has yielded unassailable results— Amazon just surpassed Wal-Mart as the world’s biggest retailer—it should be noted Amazon has earned only meagre profits despite 20 years of business. It also has one of the highest employee turnover rates in the tech sector.

Attitudes won’t change overnight. Even Fang admits she’s unable to honour her own less-is-more policy. “I honestly still work 24-7,” she says. “I can’t really commit to it because it’s my company and I need to ensure everything’s being managed.” She has, however, blocked off Sundays to catch up on laundry and grocery shopping. On Sunday evenings, meanwhile, she explores the company’s new home in Austin (SchooLinks recently relocated from Los Angeles to take advantage of a start-up accelerator program) along with her small staff. “It’s still also kind of working, I guess, doing team-building,” she says. “But I like my team—they’re also my friends—so it’s okay.”