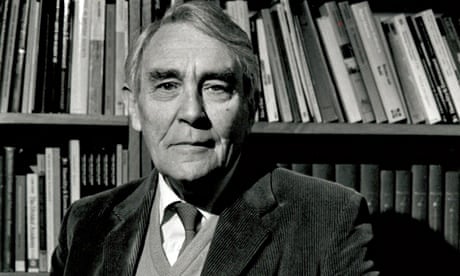

The sociologist AH Halsey, who has died aged 91, was greatly taken up with questions of inequality, social mobility and education. He was one of the most prominent academic champions of the comprehensive school, and an adviser (1965-68) to the Labour education secretary Anthony Crosland.

As a committed egalitarian, he occasionally crossed swords with the enemies of comprehensives. A notable clash came in a debate with Lord (Max) Beloff on an Open University TV programme. Beyond this commitment, Halsey never closely identified himself publicly with any particular idea or movement. While Margaret Thatcher was education secretary during Edward Heath's government of the early 1970s, he discussed with her how educational inequality could be addressed through positive discrimination. Though perhaps he could have written the definitive book on the comprehensive school that would have confirmed a position in education comparable to that of Richard Titmuss in health, it was not the path he was inclined to follow.

Indeed, although his first love was education, Halsey's published work has a much wider ambit. He edited Traditions of Social Policy (1976), a collection on the development of sociology and social work in Britain. His Origins and Destinations: Family, Class and Education in Modern Britain (with AF Heath and JM Ridge, 1980) explores the "political arithmetic" of how educational expansion has affected life chances and social mobility. The research he undertook with Ivor Crewe for the Fulton committee on reforming the civil service was published as volume three of its report (1969).

In 1989, Halsey edited an issue of the British Journal of Sociology entitled The Present State of Sociology in Britain. The general tone of this summary was optimistic. Halsey was fully aware of the low status of sociology by that time – something he wrestled with throughout his academic life. He matched this combativeness with an undisguised suspicion of some of the sister social science disciplines, especially political science. He remained positive about his own discipline, as an explicator of modern British society.

Unusually for a leftwing sociologist, Halsey was very interested in religion, and as a committed Anglican was a contributor to Faith in the City (1985), the report on urban problems by the archbishop of Canterbury's commission. This interest was also reflected tangentially in English Ethical Socialism: Thomas More to RH Tawney (1988), which he published with his lifelong friend and fellow sociologist Norman Dennis in 1988.

Towards the end of his career, Halsey took a special interest in higher education, expressed not only in his participation in the official Oxford History of the University, but also in his book Decline of Donnish Dominion (1992). Along with this went reflections as to how he and his family had got to where they were, as in No Discouragement (1996), his autobiography, and Changing Childhood (2009). He was aware that as a schoolboy he had not known of sociology, but looking back on changes in society brought home to him how much "belongingness" there had been in the world he started from. The introduction to his Essays on the Evolution of Oxford and Nuffield College (2012) pointed to the difficulty of conceptualising education and social mobility by surveying the wide range of factors that shape lives. He maintained that "social policy has to be directed not only to maximising GNP but to securing the wellbeing of individuals in a secure society. Herein lies the modern challenge: to social science, for a complex research programme aimed at solving the age-old problem of social inequality; and to politics, to discover the means to reach such a noble goal."

Albert Henry Halsey – known by his family nickname of Chelly – was born in Kentish Town, north London, son of William, a railway porter who had been gassed in the first world war, and his wife, Ada (nee Draper). He spent much of his youth in Northamptonshire, and was educated at Kettering grammar school. During the second world war he trained as a pilot in the RAF but never saw action; however, by mixing with public schoolboys less adept than he was at picking up the theory of flight, he "unlearned the attitude to university, as 'not for the likes of us'". He then attended Westminster College, a leading teacher training college, and later transferred to the London School of Economics, where he took a BSc (Econ) degree, specialising in sociology.

After graduating in 1952, he was taken on by Jean Floud for her groundbreaking research at the LSE on secondary education, the fruits of which appeared in 1956 in Social Class and Educational Opportunity, of which Halsey was a co-editor. He took posts outside London, doing research at Liverpool University (1952-54) and lecturing at Birmingham University (1954-62).

From then on, he was based in Oxford, as director of the department of social and administrative studies and fellow of Nuffield College, and from 1978 as professor, becoming emeritus in 1990. Academic honours followed in Britain and the US, including a fellowship of the British Academy. For the BBC he gave a series of Reith lectures on Change in British Society (1978).

His wife, Margaret, whom he married in 1949, died in 2004. He is survived by three sons and two daughters, eight grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

LJ Sharpe

Steven Lukes writes: Scholarship boy from a village-based railway family, then sanitary inspector's assistant and LSE graduate in its sociological heyday, Chelly Halsey was a patriot, churchman and gardener, and an Oxford professorial insider and would-be reformer. He was also an empirically committed sociologist in the tradition of Sidney and Beatrice Webb, William Booth and Henry Mayhew, who believed in "reasoned analysis and dispassionate factual investigation", and was an "unrepentant ethical socialist" in the line of descent from William Morris and RH Tawney who believed in "new freedom and new justice built on ancient solidarity".

He saw analysis and investigation as essential preconditions for turning, "as Titmuss would have said", these "romantic values" into "practical, hard-headed things" in the long "journey towards an educationally fair society".

He was seriously concerned to develop and defend British-style empirical sociology, suitably refined by American methodological advances, within educational sociology and beyond, encouraging and collaborating with younger colleagues whom he saw as sharing this vision. He was always engaged with the policy implications of such work, starting from when, as an adviser, he tried to persuade Crosland "to be a socialist", advocating at different times educational priority areas, scrapping local education authorities so that schools could be run by parents and local communities, and family policies to encourage "committed parenting".

His "romantic values" shaped the way he lived. When dining in Nuffield College he refused to drink wine, saying: "It's a gesture. I like wine. I drink it in France or somewhere where it hasn't social significance."

In 1993 he was diagnosed as needing immediate surgery for an aortic aneurysm but this was delayed three times because of the shortage of intensive care beds. The possibility of private treatment was never even considered (if the middle classes had no access to such treatment, they would exercise serious pressure to prevent delays). He spent the perilous waiting time writing letters of protest to the minister of health and his local MP.

His five children all attended comprehensive schools. He once said: "I hate hypocrisy, pomposity, the man who says he's a socialist and sends his son to Eton. You have to behave as if the revolution was here. That's how it will happen."

Albert Henry Halsey, sociologist, born 13 April 1923; died 14 October 2014

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion