Sixteen states and Washington, DC, are using their own money to keep Medicaid rates for primary care physicians at or near Medicare levels in 2015, but whether the raise has improved access to care is debatable, according to a new study published online May 11 in Health Affairs.

Healthcare access was paramount to the drafters of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), which increased Medicaid reimbursement for evaluation and management services and vaccine administration to Medicare levels in 2013 and 2014. Notoriously low rates — 59% less than Medicare's in 2012 when it came to primary care — have discouraged some physicians from accepting Medicaid patients. However, Medicaid expansion in states that chose to broaden eligibility requirements has put more people on the rolls, exacerbating the access issue. Lawmakers who wrote the ACA reasoned that a sizable raise would entice more physicians to participate in the program.

Physicians eligible for the raise in 2013 and 2014 were family physicians, general internists, pediatricians, and subspecialists related to these fields, such as pediatric cardiologists.

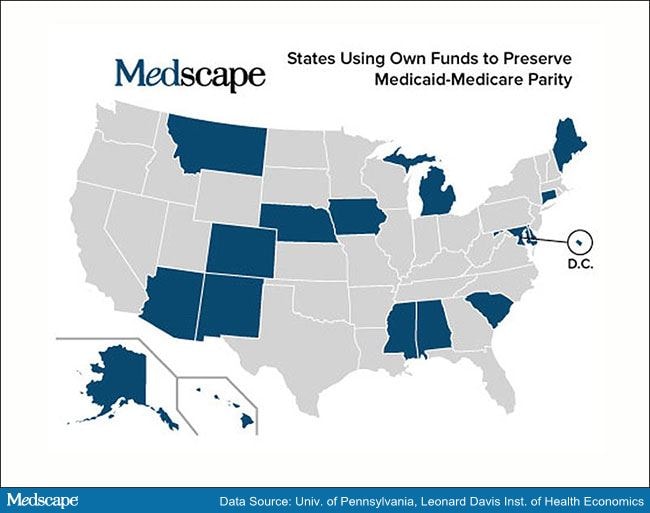

Medicaid is administered on the state level, but funded mostly by the federal government, which paid for the raise in full. The money ran out in 2015, and pleas from organized medicine for Congress to renew the raise have gone largely unheeded. However, 16 states and Washington, DC, are choosing to use their own money to preserve some, if not all, of the Medicaid pay bump (a few state programs were paying above Medicare levels before the ACA).

Is a Fee-for-Service Raise the Answer?

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services had paid states roughly $7 billion through September 2014 to boost their Medicaid rates, an amount expected to eventually reach $12 billion once all the accounting is done, according to the analysis in Health Affairs by consulting editor Laura Tollen, MPH.

However, it is hard to know what the Medicaid program got for its money other than happier physicians. Answering that question is difficult, given the 2-year time frame and a late start in 2013 to boot, writes Tollen in her review of the research into this matter. Plus, investigators face the daunting task of isolating the effect of the Medicaid raise from the fallout of hundreds of other changes in healthcare springing from the ACA.

One study of eight states issued in 2015 by the Medicaid and Children's Health Insurance Program Payment and Access Commission found that the raise "had little to no effect on Medicaid provider participation rates." Another study by the Center for Health Care Strategies on whether the higher rates attracted more providers to Medicaid yielded mixed results and no conclusions. The authors also questioned whether provider participation is a good proxy for Medicaid patients actually getting the care they need, according to Tollen.

One study of 10 states published earlier this year in the New England Journal of Medicine used a difference measurement of success — availability of an appointment for primary care — to assess the effect of the Medicaid raise. It found that appointment availability increased 7.7% for Medicaid patients compared with no increase for their privately insured counterparts. One fly in the ointment, however, was that adult Medicaid patients in the 10 states were enrolled in managed care plans. "So it may not be possible to extrapolate these findings to [fee-for-service] Medicaid environments," writes Tollen.

That limitation raises another question: How much is the Medicaid raise really needed? Tollen quotes the president of the National Association of Medicaid Directors as saying that Medicaid patients in most states usually receive primary care through managed care programs where "the doctors are [already] getting paid a lot better." For that matter, in a healthcare system moving to pay-for-performance, relying on a fee-for-service raise to bolster Medicaid strikes some experts as an outdated tactic, according to Tollen.

Meanwhile, the studies on the Medicaid pay bump keep coming. Tollen reported that the Department of Health and Human Services has commissioned RAND to analyze claims data to determine how the raise affected the patient mix of providers. She called it an "arguably better measure of access than...provider participation."

Medscape Medical News © 2015 WebMD, LLC

Send comments and news tips to news@medscape.net.

Cite this: Sixteen States Are Now Preserving Medicaid Pay Bump - Medscape - May 13, 2015.

Comments