The Plan to Move an Entire Swedish Town

Can a city pick itself up and head down the road? The people of Kiruna intend to find out.

Can a city pick itself up and head down the road? In perhaps the most radical urban relocation project so far this century, the town of Kiruna is trying to do just that. A mining settlement in Sweden’s remote far-north, Kiruna finds itself endangered by the very natural resource that gave it life: the immense seam of iron ore beneath it. If miners don’t reach new ore by tunneling deeper—as much as three-quarters of a mile down—Kiruna’s 18,200 inhabitants will face mass layoffs. And yet, deeper tunnels will leave the ground too unstable to support buildings.

Faced with either unemployment or exodus, Kiruna is choosing the latter. In so doing, it could provide other precariously located towns around the world a glimpse of their future—and some practical lessons about how to survive climate change and rising sea levels. Earlier this year, the town began its gradual move to a new site just a few miles to the east. Demolition of buildings started in the spring; by the time you read this, some of the parts of Kiruna closest to the mine will already be gone.

Though some aspects of the move may prove wrenching, the new Kiruna will be a substantial improvement over the old one, which was founded in 1900. A master plan by White, a Swedish architecture firm, provides for a denser and altogether livelier town center. Kiruna is now somewhat sprawling and unfocused. As in other towns and cities, stores have been drifting from downtown to the outskirts. Despite its small population, Kiruna has some of the downsides of a larger city: the surrounding pine forests aren’t easily accessible on foot, and depending on where you live, downtown may not be either.

The new plan gives Kiruna’s center more magnetic pull. Stores, cafés, and the town hall will be regrouped around a compact square designed by the firm Kjellander + Sjöberg, with narrow feeder streets designed to protect pedestrians from the wind. These new streets will wrap around the city square like a cocoon , making outside activities more attractive during the dark winter months and providing a key site for a biennial culture festival. The new town’s residential streets will also be surprisingly metropolitan. Residents will be concentrated in ultra-insulated (and in some cases yardless) apartments on streets arranged along an east-west axis. This plan will stretch the city into a more walkable configuration, with residents a short stroll from the forest.

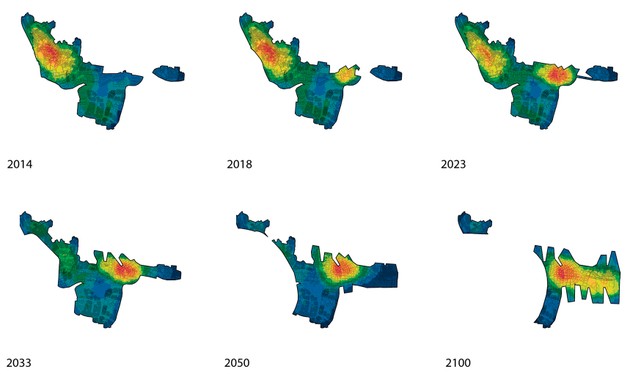

Kiruna’s move will happen slowly—very slowly. Starting with the first demolitions this spring, the town has given itself 85 years to retreat fully from the mine . The break between old and new will be neither sudden nor absolute; instead, as new neighborhoods are built on Kiruna’s eastern edge and old ones disappear, the town will inch eastward. By 2100, a greener city will have a zigzagging border that will bring fingers of open space close to the town’s heart.

Much of the old Kiruna is coming along for the ride, and with good reason. The town’s earliest structures are distinguished by durable, high-quality construction not commonly seen in frontier boomtowns.

The town plans to hold on to its best buildings, including a clock tower and a beloved church built in 1912 , by taking them apart and reassembling them in the new town center. Other materials left over from the old Kiruna will be recycled via a depot called the Portal , where residents will be able to both deposit and pick up wood, metal, and glass that could serve the new Kiruna’s rebuilding and repair needs for quite some time. Meanwhile, the old Kiruna’s site (which will remain safe to walk on) will be transformed into parkland, and a possible migration path for reindeer herds. Walking through the area in 100 years, one might not know that it had ever been a city.