Tiny Microprobes Could Explore Jupiter's Atmosphere By 2030

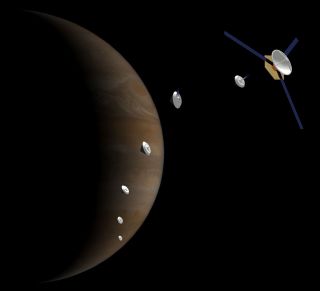

A swarm of tiny probes could zip through the clouds of Jupiter by 2030, beaming home data about the gas giant's dense atmosphere.

The bantam spacecraft should survive for about 15 minutes in Jupiter's thick air before bursting into flame, according to researchers developing a concept mission called SMARA (SMAll Reconnaissance of Atmospheres). During this brief time, the microprobes would transmit enough information to give scientists a greater understanding of the atmosphere of Jupiter.

"Our concept shows that for a small enough probe, you can strip off the parachute and still get enough time in the atmosphere to take meaningful data while keeping the relay close and the data rate high," John Moores, of York University in Toronto, said in a statement.

Moores and his team laid out the SMARA concept in a study published recently in the International Journal of Space Science and Engineering. Under their concept, the microprobes would have multiple, separate functions in order to provide the most complete picture of Jupiter's skies, study team members said. Some might take images, while others could measure the atmosphere's chemical composition.

But the SMARA mission wouldn't just improve scientists' knowledge of Jupiter, which is the closest gas giant to Earth and makes up two-thirds of the mass of the solar system, excluding the sun. SMARA could also shed light on other aspects of planetary science, such as the composition of the nebula from which the solar system formed and the nature of small cosmic bodies like asteroids, researchers said.

Studying Jupiter in depth could additionally help scientists understand gas giants outside Earth's solar system, yielding general insights about flow dynamics, cloud physics and other phenomena.

The probes' small size is essential to the scientists' plan, as larger spacecraft — anything weighing more than, say, 660 lbs. (300 kilograms) — would sample less of Jupiter's atmosphere before burning up.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Moores and his colleagues would ideally like to coordinate their mission with the European Space Agency's Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer effort (JUICE), which is scheduled to launch in 2022 and reach the Jovian system in 2030.

Tiny satellites are already making their mark in space. In February 2014, for example, astronauts on the International Space Station released a record-breaking 33 tiny satellites, also known as cubesats, into orbit.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Kasandra Brabaw is a freelance science writer who covers space, health, and psychology. She's been writing for Space.com since 2014, covering NASA events, sci-fi entertainment, and space news. In addition to Space.com, Kasandra has written for Prevention, Women's Health, SELF, and other health publications. She has also worked with academics to edit books written for popular audiences.