The Startup That Wants to Cure Social Anxiety

This Bay Area company says its website can treat the debilitating mental illness—and clinical psychology doesn’t disagree.

Brett Redding felt like he was out of options.

“It started with little things—having trouble making eye contact,” he told me.

Soon it got worse. Redding, a 28-year-old salesman in Seattle, found himself freaking out during normal, everyday conversations. He worried any time his boss wanted to talk. He would dread his regular sales calls, and the city’s booming housing market—he works in construction—seemed to make his ever-increasing meetings all the more crushing. He was suffering social anxiety, a common but debilitating mental illness.

“I was afraid of losing my job because I couldn’t do it,” he says. His meetings with a therapist weren’t working, and he didn’t “want to mess with antidepressants.”

“I’ve always been so social—I’ve never had issues with looking people in the eye and talking with people,” he says. That’s when Redding’s girlfriend saw an ad on Craigslist that promised an online program could help treat Redding’s social anxiety through methods proven by science.

“I had nothing to lose,” he says—so he signed up.

That service is now called Joyable. I first saw Joyable when an ad for it appeared in Facebook on my phone. “90 percent of our clients see their anxiety decline,” said the ad, next to a sun-glinted, bokeh-heavy photo of a blonde woman.

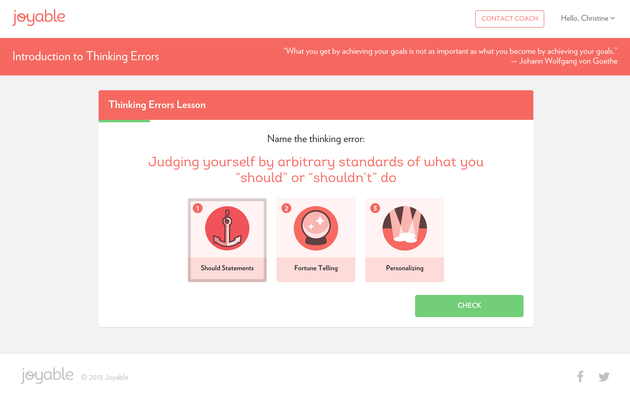

I clicked on. Joyable’s website, full of affable sans serifs and cheery salmon rectangles, looks Pinterest-esque, at least in its design. Except its text didn’t discuss eye glasses or home decor but “evidence-based” methods shown to reduce social anxiety. I knew those phrases: “Evidence-based” is the watchword of cognitive behavioral therapy, or CBT, the treatment now considered most effective for certain anxiety disorders. Joyable dresses a psychologists’s pitch in a Bay Area startup’s clothes.

Which makes a certain kind of sense, because Joyable is based in the Bay Area. Peter Shalek, its CEO, says he’s always wanted to be a therapist but has ended up founding and running companies instead. During his undergraduate years at Columbia, he founded and sold a laundry delivery service. After that, he worked as an analyst at Morgan Stanley and went to Stanford Business School. And it was there, he says—with consultation from university psychologists—that he and his cofounder created Joyable.

“I believe mental health is the single biggest waste of human potential in the developed world, and there’s quite a bit of statistics, unfortunately, to back that up,” Shalek told me. “Our mission is to cure the world of anxiety and depression.” One in four Americans suffers from a mental illness every year, and 85 percent don’t get help, he says, citing the National Alliance on Mental Illness. (The National Institute of Mental Health doesn’t issue statistics on mental health as a whole, but it estimates 28.8 percent of Americans will suffer an anxiety disorder in their lifetime. Nearly everyone agrees that the vast majority of cases go untreated.)

Though Joyable’s mission could grow to include many conditions and “hundreds of millions [of users] worldwide,” Shalek says, right now Joyable is starting with social anxiety. Why? Among other reasons, it’s the most effective: “CBT is the most effective treatment for social anxiety, bar none—it’s more effective than medication and more effective than other forms of therapy,” he says.

The research agrees. Study after study has shown that patients who are trained in CBT really do get over their anxiety, at a better rate than those using more traditional treatments like talk therapy (though many CBT therapists also deploy talk therapy-like methods).

“The core idea is that it’s not a situation that makes you anxious, but how you interpret that situation. Being on the phone is not anxiety-inducing, but how you interpret it is,” says Shalek. CBT trains patients to follow anxious thoughts all the way to their conclusion, to exhaust the brain’s ability to fret about its anxieties.

What’s more, research conducted over the past half-decade shows that CBT delivered via a website can be just as effective as CBT delivered through an in-person therapist. “It seems safe to conclude that guided self-help and face-to-face treatments can have comparable effects. It is time to start thinking about implementation in routine care,” wrote the authors of the most recent meta-analysis.

This has made CBT-by-website extremely popular in Europe and Australia, where health systems are more nationalized, says Stephen Schueller, an assistant professor of preventative medicine at Northwestern University. Schueller works in what he says is the largest team in the U.S. researching “technologies for behavioral change.” (Projects from that team include a social network meant to help depressive people.)

In the U.K., there is a version of online CBT for depression called Beating the Blues, which became popular despite only being available by prescription. “They would write you out a prescription with a web address and access code, and you’d be able to access that,” Schueller told me.

In the U.S., big managed-care consortiums like Kaiser Permanente have shown the most interest in CBT delivered through the Internet. (Kaiser has even licensed a version of Beating the Blues.) But when online CBT isn’t supported by large providers, Schueller says, it struggles to make money.

“I’ve seen a lot of people try this, and no one has been very successful at getting one to stick around,” he says. The main thing, it seems, preventing effective Internet therapy from entering the American market is … the market.

Joyable costs $99 per month or $239 for three months. It assigns every client—the site never calls them patients—a coach, who has a 30-minute-long telephone call with the patient at the beginning of their treatment. After that, the coach is available by text, email, or scheduled phone call, and they’re supposed to reach out once a week.

The coaches aren’t licensed therapists, though they are trained in CBT and motivational methods by Joyable. (They’re also all salaried, for now: “Today all of our coaches are full-time Joyable team members and they sit with us in our headquarters,” Shalek told me.)

“Imagine you wanted to get in shape and you went to the gym and had a personal trainer. They’ll tell you what to do, you do exercises, and you’d get in shape. But if you went to the gym by yourself and did those same exercises, you’d also get in shape,” says Shalek. (Or you might hurt yourself doing dead lifts—less of a liability with home CBT, though its fair to surmise that many would welcome the supervision of a trained professional.)

With the coach assigned, Joyable has three phases. First, it educates clients about how CBT approaches social anxiety with readings and interactive videos. Then, it teaches clients to recognize anxious thoughts and break them down: This, says Shalek, is the “cognitive” part of “cognitive behavioral therapy.” Finally, there’s the behavioral section, when the website guides users through small, offline activities.

“You do things that make you a little bit anxious, and in doing so you realize that the thing you’re afraid of is less likely to happen—and if it does happen, then you can cope with it,” he says. Typical activities in this phase might include getting coffee with a friend, making a phone call, or speaking up at a meeting.

Joyable opened to the public in March. In the month after it went public, its user base has multiplied by 10. (Joyable declined to release further user numbers.) The company’s cofounders said they didn’t think their product would cut into existing therapists’s business. They said it could help them: Some sufferers of post-traumatic stress disorder, for instance, suffer social anxiety along with their PTSD, but their trauma needs to be addressed and treated before they can turn to their anxiety, says Shalek. A cheery product like Joyable, which sells mental-health support like Warby Parker sells sunglasses, also reduces the stigma around seeking out therapy.

“It’s easier to tell someone, ‘I have cancer,’ than it is to tell someone, ‘I have social anxiety and depression.’ But everyone has some anxiety and depression, and everyone could be a better version of themselves if they didn’t have those feelings,” he told me. (That may be going too far—not everyone has either disorder—but Shalek is an entrepreneur, after all.)

Schueller agrees that online CBT won’t make therapists lose clients. “I see a lot of therapists concerned that this is something that will cut into their business,” he says. “The way I look at it is, a lot of people need help and aren’t getting it.”

He phrases it instead as “an issue of market segmentation.” In his home city of Chicago, he says, there are lots of therapists and it’s easy to find one. “But if I live in rural Iowa, it’s much harder to find a therapist if I need one.” Therapy-as-an-app could really help someone in a place with scant resources.

Talking to these two men, both trying to make a popular, palatable online psychological treatment, I kept thinking back to Starbucks. During its expansion in the 1990s, Starbucks aggressively opened new stores next door to local coffee houses, seeking to drive them out of business. But in many cases, Starbucks just made them more money: Visitors would pull over at the Starbucks, find it jammed with people, and try the smaller place next door. Other customers, turned on to “good” coffee by Starbucks, began to seek out even an even better cup, and they already knew where to find it.

Joyable isn’t Starbucks, and it may not be the company that manages to break online CBT out into a mainstream American audience. But there’s something potent about it. CBT is culturally ascendant, and its ideas regularly bleed over into the mainstream. When the comedian Stephen Fry writes to a fellow depressive that depressive thoughts are like stormy clouds—they are real and must be endured, but will end one day—he’s alluding to CBT ideas.

Joyable fuses two languages we’re used to—startups and psychology—and its appeal is hip, convenient, and health-focused. (Consider how many debates now are actually about psychology: The dispute over “trigger warnings” is partly about what kinds of psychological claims we can make in public debate.) And even Shalek’s words—“everyone could be a better version of themselves”—seems to fuse the sensibilities of Github and Couéism. And, most beguiling, like a new iPhone game, Joyable advertises itself to potential clients on their Facebook timelines—right where they might be feeling most anxious.

When Redding used Joyable, his coach was Steve Marks, the company’s other cofounder. Redding began using Joyable in April of last year and finished the program in July. He couldn’t endorse the service enough. One of his final exercises was a meeting he had to have with his boss. He feared getting fired: She expanded his duties and gave him a raise. Last month, nearly a year later, he found himself promoted again.

“I think CBT is so cool,” he says. “It really works. It’s so, so cheesy, but it does.”