On 1 July 2014 – Canada Day – a 15-year-old Anishinaabe girl named Tina Fontaine left Sagkeeng First Nation to visit her estranged mother in Winnipeg, Manitoba.

Five weeks later, on 8 August, Fontaine was picked up by police in a vehicle that had been pulled over for drunk driving. The police released her. Later the same day she was found passed out in a downtown Winnipeg alley. Paramedics took her to hospital, where she was handed over to a social worker. Fontaine escaped. The next day, 9 August, she was reported missing.

On 17 August, Fontaine’s body, wrapped in a plastic bag, was recovered on the muddy banks of the Red River, a meandering prairie waterway traversed by indigenous Canadians for thousands of years before the first European paddled up to what is now Winnipeg in 1738.

The death of a child anywhere provokes anger. In Winnipeg, home to Canada’s largest urban indigenous population and second in North America after Anchorage (by proportion), it has sent the city into convulsions.

The same day Fontaine was found in the alley, unconscious but alive, mayoral candidate Gord Steeves made a bold announcement: he planned to rid downtown Winnipeg of public drunkenness. Hours later, a polemic from his wife Lorrie’s Facebook page in 2010 went viral. Her complaint that she was “really tired of getting harassed by the drunken native guys” in downtown Winnipeg skywalks – “We all donate enough money to keep their sorry asses on welfare, so shut the fuck up and don’t ask me for another handout!” – has forced Winnipeg to confront an ethnic chasm, one reminiscent of nothing so much as southern US cities before the civil rights movement.

*

Winnipeg votes on a new mayor on Wednesday, and indigenous relations have dominated the race. By any metric you choose – income, education, employment, health, life expectancy, access to housing, incarceration and above all exposure to violent crime – Winnipeg’s roughly 80,000 First Nations, Métis or Inuit residents are worse off, on average, than the other 620,000 city dwellers. Closing this “great divide,” as it’s coming to be known in Winnipeg, has emerged as the city’s crucial obstacle.

Two of the candidates are indigenous: Brian Bowman, a Métis privacy lawyer who will become the first indigenous mayor in Winnipeg’s 140-year history if he can pull ahead (he’s in a statistical tie for first place) and Robert-Falcon Ouellette, a Cree university administrator polling in third. “Whoever is elected mayor has a responsibility to build bridges between the aboriginal and non-aboriginal community,” Bowman said at a fundraiser for the Winnipeg Art Gallery, which is planning on building a new structure to better display the world’s largest collection of Inuit art.

The two candiates – slender, urbanist Bowman and the PhD-educated, charismatic Ouellette – are the new faces of indigenous Winnipeg: well-spoken, suburban-dwelling professionals.

“Aboriginal Winnipeggers are the fastest-growing segment of the middle class,” trumpted Kevin Chief, the provincial minister for Winnipeg, in a sunny editorial for the Winnipeg Free Press. “All the evidence shows a big part of that success is education. This is an incredible emerging story, and Winnipeggers are recognising it and responding.”

Much of the city’s aboriginal community, however, remains underemployed, undereducated and relegated to relatively impoverished neighbourhoods in Winnipeg’s inner city and North End. Two of the three poorest postal codes in Canada are in Winnipeg. Both are predominantly indigenous neighbourhoods. They are plagued by substandard housing, inadequate financial and retail services and higher-than-average levels of violent crime, mostly because of the domestic violence associated with poverty but also because of the presence of indigenous gangs.

In an exit interview in September, outgoing mayor Sam Katz portrayed aboriginals as refugees in their own country. “I know that there’s a lot of First Nations people leaving the reserves and coming to the big city of Winnipeg. They have no training. They have no education. They have no hope,” he said. “I’m sorry, you don’t have to be Einstein to figure out what’s going to happen. They’re going to end up in gangs. They’re going to end up in drugs. They’re going to end up in prostitution. And from there, it only gets worse.”

In this divided city, those are often the only indigenous people whom some suburbanites like Lorrie Steeves see: the panhandlers, solvent abusers and mentally ill. Steeves’ rant which may have precipitated the subsequent decline of popular support for her husband, but it also garnered some praise – adding insult to injury for many indigenous Winnipeggers.

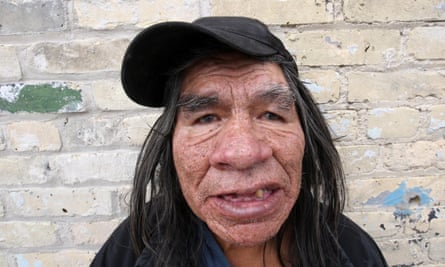

“I try not to think about stuff like that because it gets me upset,” says Jon Maytwayashing, a homeless Cree man who has lived on Winnipeg’s streets for three years. Maytwayashing wears a freshly donated winter jacket and a shoulder bag containing medication for his diabetes. He carries his clothing and personal-hygiene products within two grey plastic shopping bags. An aluminum coffee mug dangles from one finger.

We are standing at the downtown intersection of Martha Street and Henry Avenue. To the left is a 25,000-square-foot Salvation Army facility that can house 360 people. To the right is the Main Street Project, an emergency drop-in shelter and detox centre. Indigenous people are over-represented among the ranks of the homeless and addicted; solvent abuse is as common as alcoholism in this downtown district. We are mere blocks from the city’s financial core.

Being homeless isn’t easy in a city where the average overnight low in January is -23C, Maytwayashing explains. “You go anywhere you could find a heater. Heated bus shacks. Or even walking around Winnipeg Square.” That’s the financial district’s indoor mall.

The city does not lack for social organisations trying to help downtrodden indigenous people: SEED Winnipeg, which helps poor inner-city residents open bank accounts or start businesses; Ndinawe, whose indigenous-focused services range from a safe house for street kids to recreational hockey games; Ka Ni Kanichihk, which runs mentorships for teens leaving the care of child and family services; or the North End Food Security Network, which buses people who live in “food deserts” to supermarkets that sell fresh produce.

But it’s difficult when nobody seems to be addressing the root causes, say community groups. “Lots of banks and businesses have run for the hills,” said co-ordinator Jasmine Tara, who derives her funding from Neighbourhoods Alive, a provincial funding entity that’s poured millions into community-development programs in 12 Winnipeg neighbourhoods.

Part of the problem is that housing and social services are responsibilities of the province, while the cash-strapped city has chafed at getting involved in community programs out of fear that the province would offload services on to it.

The City of Winnipeg does devote $1m a year out of its $968m operating budget toward a housing-and-homelessness initiative. It also contributes $2m annually toward an urban aboriginal strategy, half of which covers indigenous job training. That’s key: indigenous people are the city’s fastest-growing ethnic group, and both the city and province want to harness it to meet labour-market needs. In doing so, they hope to kill two birds with one stone: solve the ethnic divide by creating a skilled and prosperous indigenous workforce.

“This city is going to be 20% indigenous in 10 years,” said Wab Kinew, 32, a musician, TV host and now acting associate vice-president of indigenous affairs at the University of Winnipeg. Along with other prominent leaders, the Anishinaabe-speaking Kinew has grown weary of characterising the “great divide” divide as a social problem that must be solved, rather than opportunity to be harnessed.

“We need to switch from the deficit way of thinking, where it’s all about suffering,” he says at the campus Starbucks. “We can drag our heels and cultivate a relationship that’s acrimonious and have an ‘us vs. them’ mentality. Or we can say ‘here’s a vibrant community with a beautiful culture. How do we have everyone become a successful person?’”

*

Winnipeg has a 6,000-year history of indigenous habitation. The first French-Canadian explorers only paddled up the Red less than 300 years ago, ushering in a fur trade that lasted more than 150 years. The children they had with First Nations people led to the rise of the French-speaking Métis, whose armed resistance led by Louis Riel against an influx of English-speaking Protestants resulted in the founding of Manitoba at what’s now Winnipeg in 1870. No other Canadian province was founded in an act of violence.

Many Métis were subsequently chased out of the Winnipeg area, and the young city’s first mayor was an Métis-hating racist. Meanwhile, the Canadian government established the reserve system, and spent more than a century wresting indigenous children away from their homes and placing them in residential schools, where they were forbidden to speak their languages or engage in traditional spiritual practices, and were often beaten and sexually assaulted. The goal was to assimilate the “Indian” population, who were considered less than citizens even though, as treaty signatories, they have deeply entrenched constitutional rights.

“There’s a baseline of knowledge about indigenous people and the history of this part of the world that needs to happen,” Kinew said. “Like it or not, we’re not stakeholders. We’re rights holders.”

This is not just rhetoric. The Winnipeg Police Service, for example, actively talks up the treaty relationship that grants First Nations a role in the way policing is conducted. In recent years, the police have expended considerable efforts cultivating relationships with indigenous leaders and urging them to condemn Winnipeg’s aboriginal street gangs, whose ranks include the Manitoba Warriors, Indian Posse and Native Syndicate.

Cultural awareness is also growing, said Lance Guilbault, an Anishinaabe high-school teacher at Garden City Collegiate who tries to instill a greater awareness of traditions such as sweat lodges, the four-day “sun dances” or the smudging of sage or sweetgrass.

“People have never been to a sweat to see how beautiful it is,” says Guilbault. “They’ve never smelled that wonderful sage. They’ve never come to a sun dance.” He says he wishes Winnipeg was more like cities in British Columbia, where indigenous art and imagery are woven into everything from police-car insignias to strip-mall architecture.

On a more basic level, middle-class indigenous Winnipeggers have grown weary of the persistent myth that First Nations or Métis residents don’t pay taxes or hold jobs. Oji-Cree Winnipeg artist KC Adams said her own white sister-in-law “had no idea there were so many ‘normal’ First Nations people out there” until she started playing in an aboriginal baseball league with her spouse.

“I recognized she had never seen a First Nations person outside my family, other than what she’s read in the newspaper and what she’s seen in the streets,” Adams said.

She says she’s actually thankful for Lorrie Steeves’ rant. “I’m actually grateful that post came out because it allowed a dialogue to happen. Instead of keeping it behind closed doors, we’re all having this conversation right now.”

*

The same day police recovered Fontaine’s body, they also recovered the drowned remains of Faron Hall, a Dakota man dubbed “Winnipeg’s homeless hero” because he twice saved people from drowning in the river that eventually claimed his life.

A joint vigil for Hall and Fontaine, held on 19 August, was attended by thousands of indigenous and non-indigenous Winnipeggers alike. Niigaan Sinclair, a University of Manitoba professor who helped organise the vigil, called it “one of the most remarkable and massive in Winnipeg’s history – and a turning point” in ethnic relations.

The spontaneous display of unity over the two high-profile deaths created a wave of optimism about the possibility of city-wide reconciliation – building on the spirit of Canada’s Truth And Reconciliation Commission, a nationwide effort to heal the wounds caused by the residential schools.

But when indigenous Winnipeggers learned about the police’s failure to keep tabs on Fontaine the night she disappeared, much of the euphoria fizzled. Canadian prime minister Stephen Harper’s flat refusal to launch a national inquiry into missing and murdered women also did not help the mood. A group of indigenous volunteers began to drag the Red River in an effort to find more bodies, despite suggestions bodies are highly unlikely to remain on the bottom of the high-volume waterway.

Tensions remain high. Earlier this month, Inuit singer Tanya Tagaq, winner of the Polaris Prize – the Canadian equivalent of the Mercury Prize – complained of being sexually harassed because she is indigenous. “I was in Winnipeg for the ballet, walking to lunch, when a man started following me calling me a ‘sexy little Indian’ and asking to f**k,” she tweeted. Ironically, Tagaq (a resident of Brandon, Manitoba’s second-largest city) was performing in Winnipeg as part of the Royal Winnipeg Ballet’s production of Going Home Star: Truth and Reconciliation, which depicts the sexual assault of indigenous girls at residential schools.

“That is why it is creepy and scary. It happens when we are alone. In the day or night,” Tagaq wrote, adding the hashtag #mmiw, for missing and murdered indigenous women.

Whatever the election results tomorrow, Winnipeg’s next mayor faces the not-inconsequential challenge of closing the great divide. How tough a task that will be depends on who you ask. The divide is narrowing; but candidate Ouellette believes much of that is due to more middle-class Winnipeggers choosing to self-identify as Métis. “I don’t think First Nations are doing as well as they think,” he said. “If they were, I don’t think we would have as many social issues in Winnipeg as we do.”

Last month, the brand-new Canadian Museum for Human Rights opened in Winnipeg. The irony of building a $351m shrine to human rights in a divided city is lost on no one. It looms over the Red River, which is actually a light shade of brown.

Indian v. indigenous: a glossary of terms (or, How to avoid insulting strangers in Manitoba)

Indigenous: A catchall term for Canada’s first inhabitants, which include the First Nations, Métis and Inuit.

Aboriginal: Means the same as indigenous, but is falling out of favour, especially because the term “aboriginals” – as opposed to “aboriginal people” – can be offensive.

First Nations: The Canadian equivalent to the US term “Native American” and the modern version of the usually offensive term “Indian”. First Nations are indigenous Canadians who are neither Métis nor Inuit.

Inuit: The indigenous people of Canada’s far north. Inuk is the singular form. The term replaces the archaic term Eskimos, now considered offensive.

Métis: Indigenous people of mixed European and First Nations ancestry; a distinct Métis identity was formed by the 1800s. The province of Manitoba was founded by Louis Riel, leader of the Red River Resistance, in 1870.

Native: A now-archaic and almost always offensive synonym for “aboriginal.”

Indian: An archaic and usually offensive synonym for First Nations. First Nations people, however, may use the term with impunity.

Anishinaabe: Also known as Ojibway. An Algonkian speaking group of First Nations, located in Canada in Manitoba, Quebec, Ontario, Saskatchewan and Alberta. Also located in nine midwestern US states.

Cree: Another Algonkian-speaking group of First Nations, located in Manitoba, Quebec, Ontario, Saskatchewan and Alberta, generally but not always further north than the Anishinaabe.

Oji-Cree: An Algonkian-speaking group of First Nations in Manitoba and Ontario. The Oji-Cree identity emerged from intermarriage between Ojibway and Cree.

Dene: An Athabaskan-speaking group of First Nations located in northern Manitoba, as well as in Saskatchewan, Alberta, British Columbia, the Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut.

Dakota: A Siouxian speaking group of First Nations found in Manitoba, as well as in Ontario, North and South Dakota, Montana and Saskatchewan.