What If America Had Canada's Healthcare System?

It would not be a socialist paradise. At least, not entirely.

It's not uncommon, when Republicans score a major political victory, for American liberals to throw up their hands and say, "Screw this! I'm moving to Canada."

More often than not, it's an empty threat—deterred either by the intricacies of the visa process or a glance at the January weather forecast in Winnipeg.

But what if the opposite happened? What if Canada moved here? Specifically, what if its healthcare system were to pack up, migrate southward, and rain its single-payer munificence over America, for a change?

Earlier this year, the Commonwealth Fund released a ranking of 11 developed countries' healthcare systems. The American one, the world's most expensive, ranked dead last. As I wrote at the time, the U.S. scored poorly on managing administrative hassles for both doctors and patients, avoiding emergency-room use, and reducing duplicative medical testing, among other things.

To be fair, the Canadian system didn't fare much better, coming in 10th out of 11. Still, according to a new interactive released by the Commonwealth Fund and based on the earlier report, if Americans had Canada's healthcare, we might see some surprising gains in our quality of life and reductions in our healthcare expenditures.

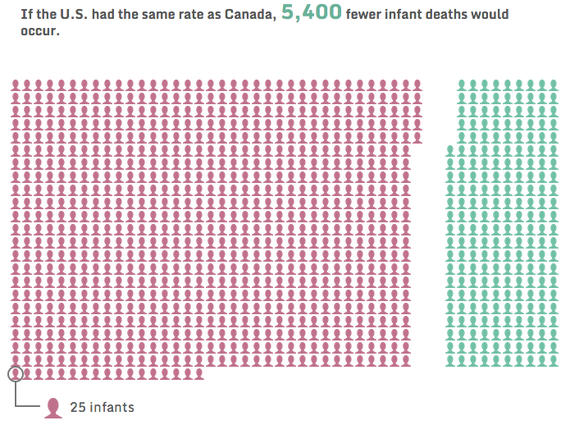

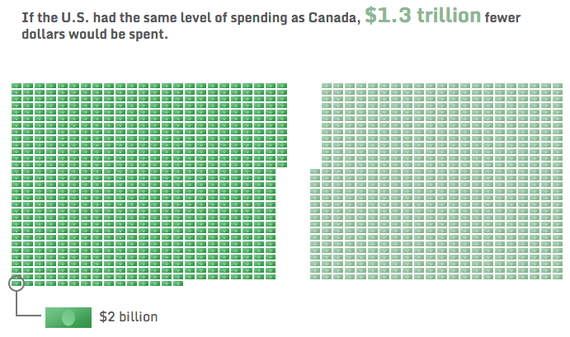

First, the good news: 5,400 fewer babies would die in infancy, and we'd save about $1.3 trillion dollars in healthcare spending. (The green blocks on the right show the number of dollars or lives saved, while the red blocks on the left show the expenditures or deaths that would still happen.)

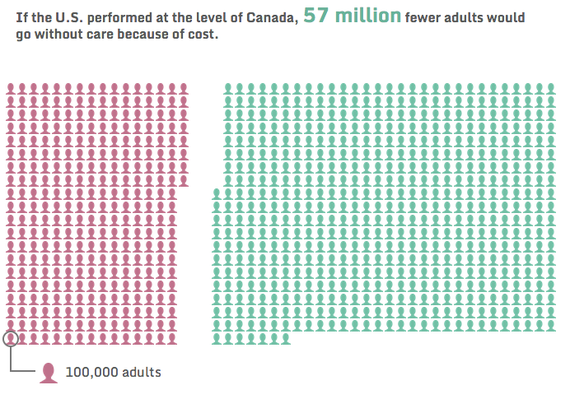

What's more, 57 million fewer people would go without medical care because of the cost. "Roughly 40 percent of both insured and uninsured U.S. respondents spent $1,000 or more out-of-pocket during the year on medical care, not counting premiums," the report authors write. (Though, it's worth noting that the data for the report was collected before the full implementation of Obamacare, which dramatically expanded health insurance coverage in the U.S.)

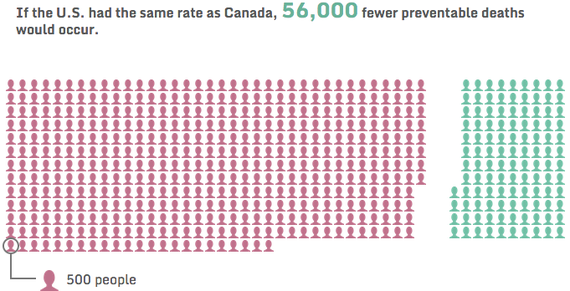

And, perhaps as a result, more than 50,000 preventable deaths would be avoided:

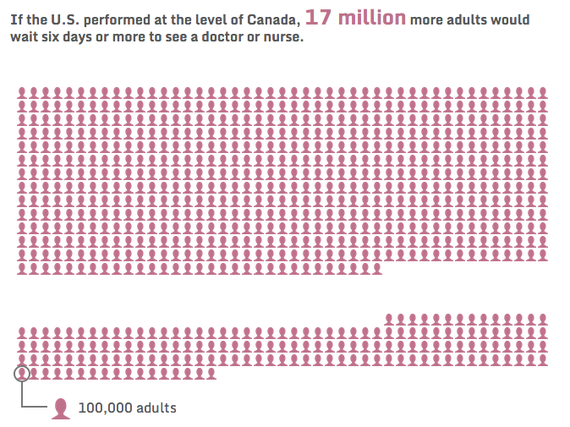

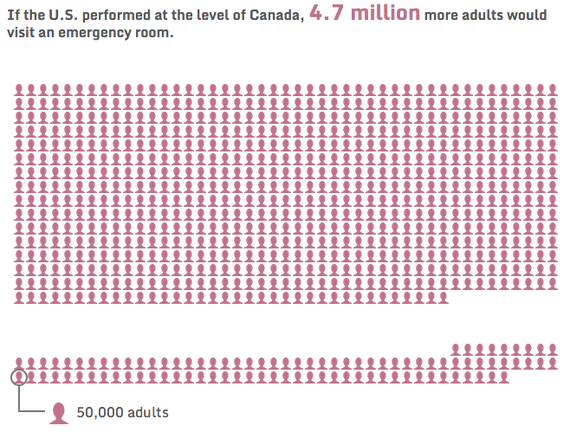

But it wouldn't all be good news. Canada's free system comes at the cost of greater wait times for some services. In 2010, the Commonwealth Fund found that 33 percent of Canadians waited six days or more to see a specialist, compared with 19 percent of Americans. And Canadians tend to wait longer for ER care than patients in other countries: One in 10 patients in a Canadian ER will wait eight hours or more, and the average wait time is four hours. (Here, the shorter red blocks below represent how many additional patients would have to wait or would visit the ER if we had the Canadian system.)

On top of that, more people would visit the ER in general:

That last point could either be a positive or negative, depending on how you look at it. On one hand, having lots of ER patients is expensive and inefficient for hospitals, and Canadians might be headed to emergency departments because wait times for regular doctors are too long. But on the other hand, it's free for patients—so, some might wonder, why not use it if it's there?

The Commonwealth Fund site's interactive allows users to compare the healthcare systems of 11 different countries, so if Canada's not your cup of tea, you can try, say, England, or Sweden, or France. Bon healthcare voyage!