I first discovered Dune through David Lynch’s 1984 film adaptation of Frank Herbert’s SF masterpiece. The “Lynchian” style, that novelist David Foster Wallace would later define as “a particular kind of irony where the very macabre and the very mundane combine”, would spin wildly out of control in the Dune universe, where the very macabre combines with … the even more macabre. Nonetheless, Lynch’s broken but mesmerising space-opera-come-art-film remains the best adaptation in a franchise that has been much abused over its 50 year history.

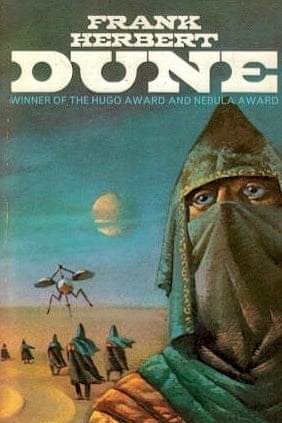

Dune the novel was initially published in two parts, Dune World and Prophet of Dune, in Analog magazine. The full book was published in 1965, and would go on to win the Hugo award the following year, making it an immediate hit with science fiction audiences. Dune’s central conceit, of a feudal fantasy world recast in interstellar space, was not unique. Neither was the archetypal story of a disinherited prince reclaiming his realm. But the themes of ecology, drug use and spiritual enlightenment that Herbert wove into the tapestry of Dune made it vibe with the counter-cultural audience of the 60s and 70s.

It was the messianic journey of Paul Atreides, transformed from a young prince to nothing less than the omnipotent Emperor of the entire universe, that truly captured the hearts and imagination of Dune’s predominantly male audience. Dune is a boy’s own adventure, wrapped in an adolescent coming of age story, spliced with a Bildungsroman, in which boys become men by taming a giant worm and women only appear as princesses, priestesses or temptresses. It’s a book that boys and young men of a certain temperament – intelligent, introverted, angry – often obsess over. Dune is a potent wish-fulfilment fantasy, allowing its readers to play out the status and power they lack in the real world.

Sci-fi owes much of its popularity to film and television, and like many of the most successful books in the genre, Dune’s prose style seeks to reproduce a cinematic reading experience for its audience. Frank Herbert mastered a close third person style that would influence many writers who followed, and has become the standard for commercial SF and Fantasy novels. George RR Martin’s hugely successful Game of Thrones novels clearly took some inspiration from Dune, right down to presenting each character’s inner thoughts as italicised sentences. It’s a style that makes Dune easy for infrequent readers to digest, but equally hard for literary readers to stomach.

Dune’s cinematic qualities have made it a natural target for Hollywood adaptations. But the Lynchian weirdness, followed by a lacklustre mini-series, have left the franchise in a televisual limbo for most of the last two decades. Herbert’s own sequels, while conceptually interesting and widely loved by established fans, lack the storytelling muscle displayed in the first book. A risible series of cash-in prequels have dragged the Dune universe down to the bargain basement of pulp fiction. It’s a sad legacy for such a significant work of fiction.

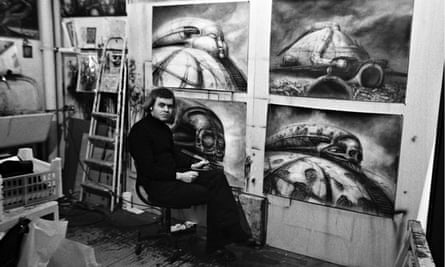

Like a desert planet returning to life, excitement bloomed around Dune again in 2013 with the release of Jodorowsky’s Dune, a documentary film that revealed the unmade movie adaptation that might have been by Alejandro Jodorowsky. A decade before Lynch’s version, Chilean cult movie-maker Jodorowsy planned an even more baroque film, which would have starred Salvador Dalí, Orson Welles and Mick Jagger (presumably stepping naked out of a steam shower in place of Sting) with designs by sci-fi legends HR Giger and Chris Foss.

As it faces its 50th anniversary, Dune may seem to be a story fading into the past. But I suspect there’s life in Frank Herbert’s masterpiece yet. Following the recent successes of Gravity and Interstellar, there’s a taste for epic sci-fi in Hollywood again. And as the recent #gamergate saga confirmed, there’s no lack of angry, alienated young men begging for stories that put them at the centre of a fictional universe. But even 50 years after they reached their pinnacle, it’s Frank Herbert’s skills as a storyteller that will keep Dune alive for many decades to come. Because if there is one truly immortal thing in the universe, it’s a great story.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion