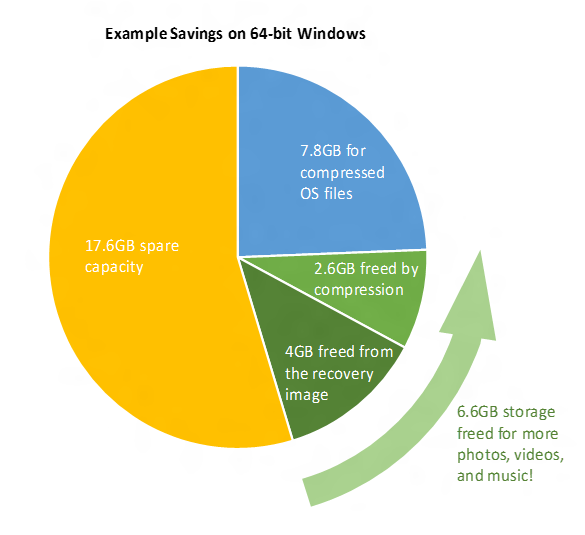

With the Windows 8.1 Update, Microsoft shrank the Windows 8.1 install footprint to make it suitable for low-cost tablets with just 16GB of permanent storage, a reduction from the 32GB generally required for Windows 8. Windows 10 will shrink the disk footprint further, potentially freeing as much as 6.6GB of space on OEM preinstalls.

Microsoft describes two sources of savings. The first is the re-use of a time-honored technique that fell out of fashion as hard drives grew larger and larger: per-file compression.

The NTFS filesystem used in Windows has long allowed individual files and folders to be compressed, reducing their on-disk size at the expense of a small processor overhead when reading them. With spinning disks getting so large as to feel almost unlimited, per-file compression felt like a relic from a bygone age by the mid-2000s. But with the rise of solid state storage and ultra-cheap devices with just a handful of gigabytes available, per-file compression has gained a new lease on life.

When installing Windows 10 from scratch, it will assess the system's performance to figure out if the system processor is fast enough that it can decompress system files without any noticeable performance impact. If it's fast enough (and it's hard to imagine a system built in the last decade that wouldn't be fast enough, though Microsoft doesn't appear to have disclosed the exact requirements) then a selection of system files will be stored compressed on disk. Store apps are also eligible for compression.

To enable high performance decompression, Microsoft has added a number of new compression algorithms to the NTFS filesystem that are designed for compressing executable files. These all appear to be variants of algorithms already well used and tested in other Windows software; three are variants of the "Xpress" algorithm used for hibernation files, Windows Updates, and the Windows Imaging Format (WIM) files used by the Windows installer. The fourth algorithm, LZX, is used in Microsoft's CAB archives, and it's also an option for WIM. The different algorithms each offer different size/space trade-offs. These join the LZNT1 algorithm that's more suitable for general data compression.

In total, Microsoft reckons that compression can save 1.5GB on 32-bit systems and 2.6GB on 64-bit ones. These savings extend to Windows 10 for Phones, too.

The second set of savings come from eliminating something that takes up a ton of disk space: the recovery image. OEM systems have a hidden partition containing a fresh image that's used for system recovery. At a bare minimum this will usually take about 4GB of space; with a ton of pre-installed software (or just sloppy sizing), it can take much more. With Windows 10, the entire thing is eliminated.

This isn't Microsoft's first attempt to reduce the space required for recovery. Windows 8.1 Update introduced a clever space-saving technique to save the recovery partition space; instead of duplicating the recovery files onto the working Windows install (and thereby doubling the amount of space required), the working install just contained pointers to the files on the recovery partition. This is what enabled the use of 16GB drives. However, the technique was complicated to administer and setup, so Microsoft has gone back to the drawing board in Windows 10.

Windows 10's recovery will simply use the system files from the working operating system. Windows already knows which files belong to Windows and which ones don't; to reset the PC, it simply needs to delete everything that isn't Windows and restore the registry and other settings files to sensible defaults.

The savings from eliminating the restore image won't apply to Windows 10 on phones, because they already use a similar mechanism for their reset process.

As well as reducing the disk footprint, this should make restoring faster, because it will remove the need to download security updates and operating system patches after recovery: the Windows system files used for recovery will already be the up-to-date patched versions. This addresses one of the biggest problems with recovery partitions: they're essentially unserviceable, and every time a system is restored using one, it becomes immediately susceptible to security flaws.

We do wonder if it will offer the same robustness as a recovery partition, however. Although deleting system32 is harder to do than it used to be—much to the chagrin of 4chan trolls everywhere—the in-use operating system files still feel more immediately vulnerable to damage or destruction at the hands of malicious or broken software.

Windows 10 will still be able to recover from such scenarios, provided that you make recovery media of your own.

The only sticking point, currently, is those 16GB Windows 8.1 Update machines using its clever space-saving recovery image technique. To ensure that a failed upgrade can be safely rolled back, upgrading those machines to Windows 10 requires enough space for both operating systems to exist side-by-side. Microsoft isn't yet sure how to handle these machines, but it's apparently evaluating "a couple of options" to allow them to upgrade.

reader comments

118