Environment

Departing Earth

What does it say to leave your home planet forever?

Posted March 27, 2015

In the early 2000s I attended a public lecture by the eminent physicist Freeman Dyson at the University of California, Berkeley, about recent discoveries in physics and astronomy. At the end of his talk an audience member questioned Dyson on the role of biotechnology and genetic engineering, a controversial subject that includes the specter of designer babies, plants that produce their own pesticides, and tomatoes with genes taken from fish—developments that could affect society in myriad positive and negative ways.

Dyson told the audience that genetic engineering is very important because we’ve damaged the ecosystems of Earth so badly that we’ll have to genetically engineer the human species to be able to live somewhere off the planet. Our descendants will need bodies with lungs that work in atmospheres with less oxygen and bones that require less gravity, for example.

![By NASA [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons By NASA [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://cdn.psychologytoday.com/sites/default/files/styles/article-inline-half/public/field_blog_entry_images/Mars_atmosphere_2.jpg?itok=4J4jSdRx)

While I accept the authority of scientists over scientific findings, I deplore the way in which our technophilic society sometimes treats scientists as priests who can tell us how we should act on these findings. Such decisions as whether to begin genetically engineering humans or to release genetically modified crops into the biosphere need the full and democratic participation of the public (informed by the best science and scientists). Such developments have many political, legal, social, and ethical consequences that will shape life for future generations. Who gets to decide what traits go into the babies? How much will it cost and who will pay? Will poor people’s babies be left behind?

Dyson surely has a right to his opinion, but I hope that people will take it with a grain of salt. The idea that we should use technology to engineer humanity so that we can no longer be dependent on Earth alleviates us from responsibility to care for and nurture this planet, which is still beautiful and bounteous. Dyson’s suggestion is an example of techno-salvation: more and better science and technology will allow us to surmount all problems. Yet after five centuries of modern science and technological development, ecological conditions on Earth only seem to be getting worse on the whole, and many people are looking at psychological and philosophical reasons for this trend.

The idea of escaping the planet—running away from the mess we’ve created here—is certainly not the answer. It only takes a few minutes of contemplating this cycle of destroy-and-move-on to realize how terminally ill it is. We would just take it with us to the next place(s) we settle and damage them. It’s a destructive logic that drives the environmental crisis.

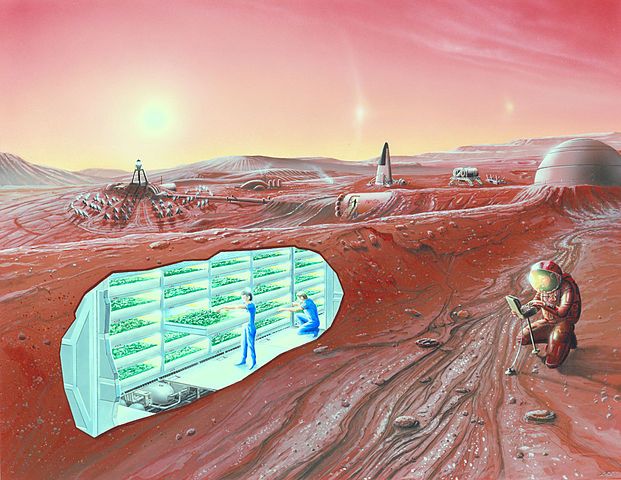

I wonder about the psychology of escapism also when I hear of projects such as the “Mars One” mission, aimed at putting people on the red planet by the mid 2020s.[1] Over the last century many schemes have been hatched to put people on Mars. Because of the logistics and huge expense of bringing people back, “Mars One” intends to send its astronauts there on a one-way trip: they’ll never return to Earth. Two hundred thousand people from around the world have volunteered.

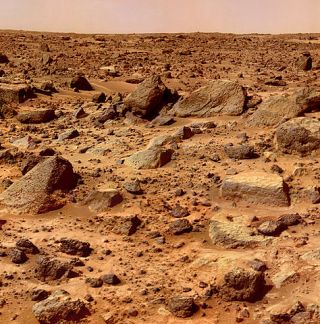

On one level, the mission could produce invaluable scientific findings and engineering developments. But on another, the idea of permanently leaving Earth, never to wander outside again in the fresh air, never to be in a natural environment, always enclosed by artificial surroundings and vulnerable to tenuous life support systems, reminds me of Dyson’s suggestion that we give up on Earth. To me, it boggles the mind that people would choose to surrender the chance to be in nature ever again—or face to face with their families or friends.

Someone should do a study of the psychology of people willing to permanently leave their homes, families, and planet. Certainly, it would be thrilling to be part of such a mission, part of such a complex network of systems and engineers. But to never come back, with no option to change your mind? What does this say about people’s attachment to place (or lack thereof)? In some senses we are already quite disconnected from nature in our everyday lives, which we live mostly inside cars, homes, and offices, in front of screens most of the day (for most of us). Perhaps we have already partly departed from Earth and nature. Maybe Mars is just the next logical step in this retreat?

In my view the Mars One mission is unlikely to take place, at least in the timeframe given, because the technical and psychological hurdles are so great (think of the failure of Biosphere 2, the project to house people in a fully closed ecological system here on Earth). But I hope that these volunteers for Mars are not the pioneers of a long-range movement to abandon this glorious and irreplaceable blue marble we call home.

My book: Invisible Nature

Follow me: Twitter or Facebook

My environmental blog: Finding the Human Place in Nature

Read more of my posts: The Green Mind

[1] http://www.mars-one.com, http://www.cnbc.com/id/102531473, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mars_One, http://www.timeslive.co.za/scitech/2015/03/23/finalist-criticises-mars-….