How to Write: A Year in Advice from Franzen, King, Hosseini, and More

Highlights from 12 months of interviews with writers about their craft and the authors they love

This year, I talked to nearly 50 different writers for the By Heart series, a weekly column about beloved quotes and cherished lines. Each author shared the life-changing, values-shaping passages that have helped sustain creative practice throughout his or her career. Their contributions were eclectic and intensely personal: Jim Crace, whose novel Harvest was a finalist for the Man Booker prize this year, shared a folk rhyme from his childhood, the investigative New York Times journalist Michael Moss (Salt, Sugar, Fat) close-read the Frito-Lay slogan, and This American Life host Ira Glass eulogized a longtime friend and collaborator. Though I began by asking each writer the same question—what line is most important to you?—their responses contained no formula.

There was also no specific requirement to talk about craft. And yet writers—being writers—offered a generous bounty of practical writing advice. They shared exercises. They discussed principles of revision. Some presented ways to beat procrastination, or fight back against writing-desk ennui. And a great many shared their thoughts on the most crucial craft question of all: Why does some writing feel dead on the page, while other words thrum with life?

Taken together, these conversations were like attending an MFA program—I learned that much. Here are the best short pieces of writing advice I heard from writers in 2013, a whole year’s worth of wisdom.

Khaled Hosseini, author of The Kite Runner and this year’s And the Mountains Echoed, reminded us that we can only approximate the book we want to write—the final product will never capture the excitement of initial inspiration. His tribute to Stephen King explained how he deals with that familiar disappointment.

You write because you have an idea in your mind that feels so genuine, so important, so true. And yet, by the time this idea passes through the different filters of your mind, and into your hand, and onto the page or computer screen—it becomes distorted, and it's been diminished. The writing you end up with is an approximation, if you're lucky, of whatever it was you really wanted to say.

When this happens, it's quite a sobering reminder of your limitations as a writer. It can be extremely frustrating. When I'm writing, a thought will occasionally pass unblemished, unperturbed, through my head onto the screen—clearly, like through a glass. It's an intoxicating, euphoric sensation to feel that I've communicated something so real, and so true. But this doesn't happen often. (I can only think that there are some writers who write that way all the time. I think that's the difference between greatness and just being good.)

Even my finished books are approximations of what I intended to do. I try to narrow the gap, as much as I possibly can, between what I wanted to say and what's actually on the page. But there's still a gap, there always is. It's very, very difficult. And it's humbling.

But that's what art is for—for both reader and writer to overcome their respective limitations and encounter something true. It seems miraculous, doesn't it? That somebody can articulate something clearly and beautifully that exists inside you, something shrouded in impenetrable fog. Great art reaches through the fog, towards this secret heart—and it shows it to you, holds it before you. It's a revelatory, incredibly moving experience when this happens. You feel understood. You feel heard. That's why we come to art—we feel less alone. We are less alone. You see, through art, that others have felt the way you have—and you feel better.

Jim Shepard, author of Love and Hydrogen, argued against the conventional literary wisdom that has prevailed since Joyce: that short stories should be structured around a life-changing epiphany. In his reading of Flannery O’ Connor’s classic story “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” suggests moments of insight don’t last—and knowing this is key to crafting realistic characters.

O'Connor really believes that we can flood, momentarily, with the kind of grace that epiphany is supposed to represent. But I think she also believes that we're essentially sinners. She's saying: Don't think for a moment that because you've had a brief instant of illumination, and you suddenly see yourself with clarity, that you're not going to transgress two days down the road.

I find this idea enormously useful in my own work. My characters are all about gaining an understanding of the right thing to do—and avoiding it anyway. That sense that we can be in some ways geniuses of our own self-destruction runs, in some ways, counter to the more traditional notion of the epiphany—which tells us that stories are all about providing information to characters who badly need it. Epiphanies are, in some ways, staged and underimportant.

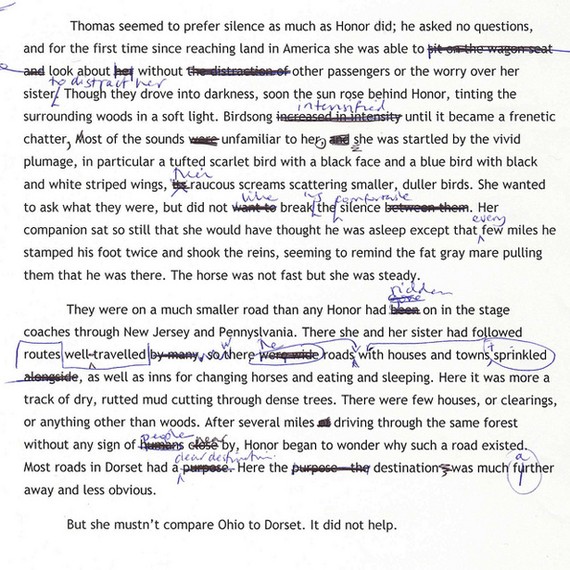

Tracy Chevalier, author of Girl With a Pearl Earring, praised the minimalist designer Mies van der Rohe—and his famous mandate “Less is more.” She shared how she trims the narrative fat, and why concision matters.

Taking away concentrates what's left. Restraint is powerful. In Girl With a Pearl Earring, the two main characters touch just twice—a hand, an ear—but readers tell me those are some of the most erotic moments they've read. In my new novel, The Last Runaway, the heroine is a Quaker and says little, in keeping with the tradition of silence at Quaker meetings. Through the drafts I kept cutting her lines, so that now when Honor Bright speaks, you notice.

By using fewer words, I am also giving readers the chance to fill the gaps with their own. "Less is more" encourages collaboration, which is what a book should be—a contract between writer and reader.

Chevalier also showed us this process at work:

Fay Weldon acknowledged that, on a day-to-day level, writing can seem like pointless drudgery. She described how Camus’s aphorism “One must imagine Sisyphus happy” helps her fight back against unproductive feelings of meaninglessness.

If we consider, like Camus, Sisyphus at the foot of his mountain, we can see that he is smiling. He is content in his task of defying the Gods, the journey more important than the goal. To achieve a beginning, a middle, an end, a meaning to the chaos of creation—that's more than any deity seems to manage: But it's what writers do. So I tidy the desk, even polish it up a bit, stick some flowers in a vase and start.

As I begin a novel I remind myself as ever of Camus's admonition that the purpose of a writer is to keep civilization from destroying itself. And even while thinking, well, fat chance! I find courage, reach for the heights, and if the rock keeps rolling down again so it does. What the hell, start again. Rewrite. Be of good cheer. Smile on, Sisyphus!

For Mohsin Hamid, author of How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia, physical exercise helped break through writer’s block. Following the counsel of literary ultra-marathoner Haruki Murakami, Hamid found that long, daily walks made him more creative.

I needed to get unstuck. And, nearing the age of 40, I'd already used up many of the usual tricks writers before me had employed to shake things up when they were in a rut: travel chemically, break your heart, change continents, get married, have a child, quit your job, etc. I was desperate. So I started to walk. Every morning. First thing, as soon as I got up, which as a dad now meant 6 or 7 a.m. I walked for half an hour. Then I walked for an hour. Then I walked for 90 minutes…

Murakami's quote is about writing long novels. I write short novels. So it made sense that while he has to run to get fit enough to do what he has to do, I could manage with just walking. And, the significant speed difference notwithstanding, a daily five-mile walk turned out to be exactly what I needed. My head cleared. My energy soared. My neck pains diminished. Sometimes I texted myself ideas, sentences, entire paragraphs as I walked. Other times I just floated along, arms at my sides, stewing and filtering and looking.

Walking unlocked me. It's like LSD. Or a library. It does things to you. I finished my novel in only two more years (for a total of six), walking every day. And I don't plan on stopping. If the choice is between extended periods of abject writing failure and prescription orthotics, I know which side my man Murakami and I are on.

Michael Pollan advocated getting one’s hands dirty. For him, the act of starting a garden helped him develop the questions he never could have posed abstractly—through gardening and the work of Wendell Berry, he uncovered his subject and approach.

I'd learned a set of values from Thoreau in the library, but it was only when I tested them—in the crucible of an actual garden with actual pests on an actual patch of land—that I was able to form my values more fully.

It was in reading Wendell Berry that I came across a particular line that formed a template for much of my work: "eating is an agricultural act." It's a line that urges you to connect the dots between two realms—the farm, and the plate—that can seem very far apart. We must link our eating, in other words, to the way our food is grown. In a way, all my writing about food has been about connecting dots in the way Berry asks of us. It's why, when I write about something like the meat industry, I try to trace the whole long chain: from your plate to the feedlot, and from there to the corn field, and from there to the oil fields in the Middle East. Berry reminds us that we're part of a food system, and we need to think about our eating with this fact—and its implications—in mind.

Ultimately, this revelation led to a change in my career. I was an editor at Harper's, and I loved editing magazines. I didn't think it was ever realistic that I could make a living as a writer, but my editorial work—helping writers with their prose, watching the process of revision, finding a narrative paths through a complex subject—made me increasingly curious to try it myself. I didn't have a subject until I kind of hit on the garden by mistake. And by engaging with my own agricultural struggle on a small scale, I became reoriented: I learned a way of thinking and living that I didn't know before. I wanted to write more and more about the agricultural and political realities I am joined to by my eating.

Jessica Francis Kane has taken solace over the years in the Stoic philosopher Marcus Aurelius. His injunction—“What is there in this that is unbearable and beyond endurance?”—helps her remember that facing the blank page is not so relatively painful, and this helps her stop procrastinating.

Writing is hard, but is it unbearable? Who would say that it is? Even asking the question, I'm reminded of the one exclamation in the passage: "You would be ashamed to confess it!" His words helped me navigate rejection, which is certainly no fun, but if you ask yourself if it's unbearable, you find yourself preparing the next self-addressed stamped envelope pretty quickly. The words helped me survive the protracted sale of my first novel, and they reminded me to start writing again after a long hiatus after the birth of my first child. I wasn't sure how to make room for writing with a baby. It is difficult, but beyond endurance? I got myself back to the desk.

Stephen King’s classic craft memoir On Writing addresses almost everything the master storyteller knows. But one key topic is not covered in that book: how to write a perfect opening sentence. King shared his thoughts, developed over many years of writing, on how books should start and why beginnings matter.

A book won't stand or fall on the very first line of prose -- the story has got to be there, and that's the real work. And yet a really good first line can do so much to establish that crucial sense of voice -- it's the first thing that acquaints you, that makes you eager, that starts to enlist you for the long haul. So there's incredible power in it, when you say, come in here. You want to know about this. And someone begins to listen.

Paul Harding, author of Enon, explained how juxtaposition and contradiction underlie great fiction—and held up John Cheever as a sterling example of this principle at work.

Contradiction is the essential move or method for art. In music it’s counterpoint. In landscape painting it’s the contrast between the foreground, which is always dark, and the background, which is light. And in writing, it’s death and life. The imminent arrival of death—what greater thing to set life in relief against? In Enon, the whole thing is just a sonata—it’s just one voice—against the threat of utter darkness. The darker it gets, when we arrives at just one remaining pinpoint of light, that pinpoint becomes all the more beautiful and resplendent for its rarity and clarity against the gloom. You put contradictory things next to each other, and in the intermingling of them you get something like the mystery of human experience.

The same kind of principle works for juxtaposition—the infinite with the infinitesimal. This works in writing, when you describe something on the scale of the universe, and then describe something as tiny as a grain of sand. So you could take a tiny, intimate domestic scene—someone drinking a cup of tea at a desk—that scalability, that intuitive human truth that the great and the small, the good and the bad, the light and the dark, are all intermingled.

The poles must be structured around the truly irreducible questions—mysteries you can’t get to the bottom of. Otherwise, you’re in danger of explaining yourself away. Second-rate writing will tell you which pole to pick: “Be kind to strangers!” Then you’re in the realm of propaganda or received opinion or truisms. I think the definition of kitsch, or sentimentality, is denying either pole in favor over the other. It goes back to what Cheever’s character, is attempting but failing, to do—trying to deny the dark part and show only the light. But in the model, that conceptual model, no subject has any meaning if it’s been separated from its opposite. It’s Einstein, it’s relativity: Nothing has meaning without being relative to its opposite.

In the digital age, people are more seamlessly connected than ever before. Jonathan Franzen reminded us that fiction writers must be singular. He explained why great writing happens far from the cloud, the crowd:

The Internet is fabulous for a lot of things. It’s a fabulous research tool. It’s great for buying stuff, it’s great for bringing together people to work on communal things, like software, or people who share a passion or are all suffering from the same disease and want to find each other and communicate. It’s wonderful for that. But the Internet in general—and social media in particular—fosters this notion that everything should be shared, everything is communal. When it works, it’s great. But it specifically doesn’t work, I think, in the realm of cultural production—and particularly literary production. Good novels aren’t written by committee. Good novels aren’t collaborated on. Good novels are produced by people who voluntarily isolate themselves, and go deep, and report from the depths on what they find. They do put what they find in a form that’s communally accessible, communally shareable, but not at the production end. What makes a good novel, apart from the skill of the writer, is how true it is to the individual subjectivity. People talk about “finding your voice”: Well, that’s what it is. You’re finding your own individual voice, not a group voice…

And this is true, especially true, for anyone who aspires to write serious fiction. When I first met Don DeLillo, he was making the case that if we ever stop having fiction writers it will mean we’ve given up on the concept of the individual person. We will only be a crowd. And so it seems to me that the writer’s responsibility nowadays is very basic: to continue to try to be a person, not merely a member of a crowd. (Of course, the place where the crowd is forming now is largely electronic.) This is a primary assignment for anyone setting up to be and remain a writer now. So even as I spend half my day on the Internet—doing email, buying plane tickets, ordering stuff online, looking at bird pictures, all of it—I personally need to be careful to restrict my access. I need to make sure I still have a private self. Because the private self is where my writing comes from. The more I’m pulled out of that, the more I simply become another loudspeaker for what already exists. As a writer, I’m trying to pay attention to the stuff the people aren’t paying attention to. I’m trying to monitor my own soul as carefully as I can and find ways to express what I find there.

Andre Dubus III made the case against outlining. In his warning against intellectualizing one’s work—“Do not think, dream”—he insisted that fiction comes to life when you stop trying to control it by working towards an ending planned out in advance.

We’re all born with an imagination. Everybody gets one. And I really believe—this is just from years of daily writing—that good fiction comes from the same place as our dreams. I think the desire to step into someone else’s dream world, is a universal impulse that’s shared by us all. That’s what fiction is. As a writing teacher, if I say nothing else to my students, it’s this.

I began to learn characters will come alive if you back the fuck off.

Here’s the distinction. There’s a profound difference between making something up and imagining it. You’re making something up when you think out a scene, when you’re being logical about it. You think, “I need this to happen so some other thing can happen.” There’s an aspect of controlling the material that I don’t think is artful. I think it leads to contrived work, frankly, no matter how beautifully written it might be. You can hear the false note in this kind of writing.

This was my main problem when I was just starting out: I was trying to say something. When I began to write, I was deeply self-conscious. I was writing stories hoping they would say something thematic, or address something that I was wrestling with philosophically. I’ve learned, for me at least, it’s a dead road. It’s writing from the outside in instead of the inside out.

But during my very early writing, certainly before I’d published, I began to learn characters will come alive if you back the fuck off. It was exciting, and even a little terrifying. If you allow them to do what they’re going to do, think and feel what they’re going to think and feel, things start to happen on their own. It’s a beautiful and exciting alchemy. And all these years later, that’s the thrill I write to get: to feel things start to happen on their own.

So I’ve learned over the years to free-fall into what’s happening. What happens then is, you start writing something you don’t even really want to write about. Things start to happen under your pencil that you don’t want to happen, or don’t understand. But that’s when the work starts to have a beating heart.

Sherman Alexie, author of Lone Ranger and Tonto Fistfight in Heaven, explained how writers are kept captive by the things that torment them—in his case, it was his upbringing on an Indian reservation—but in our childhood prisons lie the seeds of inspiration. He urged us to reclaim our traumas and make great art.

We tend to revisit our prisons. And we always go back. This is not only true for reservation Indians, of course. I have white friends who grew up very comfortably, but who hate their families, and yet they go back everything Thanksgiving and Christmas. Every year, they’re ruined until February. I’m always telling them, “You know, you don’t have to go. You can come to my house.” Why are they addicted to being demeaned and devalued by the people who are supposed to love them? So you can see the broader applicability: I’m in the suburb of my mind. I’m in the farm town of my mind. I’m in the childhood bedroom of my mind.

I think every writer stands in the doorway of their prison. Half in, half out. The very act of storytelling is a return to the prison of what torments us and keeps us captive, and writers are repeat offenders. You go through this whole journey with your prison, revisiting it in your mind. Hopefully, you get to a point when you realize there was beauty in your prison, too. Maybe, when you get to that point, “I’m on the reservation of my mind” can also be a beautiful thing. It’s on the rez, after all, where I learned to tell stories.

Aimee Bender, author of The Color Master, said that the best writing is enigmatic—she lets the music language guide her, rather than traditional notions of plot, character, and knowing where she’s going.

The writing I tend to think of as “good” is good because it’s mysterious. It tends to happen when I get out of the way–-when I let it go a little bit, I surprise myself. I feel most pleased with my language when I don’t understand it completely. When it sustains hope that there’s more to write about, that there’s an open door for me to explore. That’s when the writing gets really fun. I feel like it’s all about waiting for a kind of discovery that takes place on the sentence level—as opposed to having a light-bulb about a character. That’s the thing that drives me from first sentence to last sentence.

I know my own writing is working when I feel like there’s something hovering beneath the verbal, that mysterious emotional place.

Language is the ticket to plot and character, after all, because both are built out of language. If you write a page a day for 30 days, and you pick the parts where the language is working, plot and character will start to emerge organically. For me, plot and character emerge directly from the word—as opposed to having a light-bulb about a character or event. I just don’t work like that. Though I know some writers do, I can’t. I’ll think, oh I have an insight about the character, and when I’ll sit down to write, it feels extremely imposed and last for two minutes. I find I can write for two lines and then I have nothing else to say. For me, the only way to find something comes through the sentence level, and sticking with the sentences that give a subtle feeling that there’s something more to say. This means I’ve hit on something unconscious enough to write about—something with enough unknown in there to be brought out. On some level I can sense that, and it keeps me going….

Some of those mysteries clarify, but they’re not all going to clarify. I think a good poem will always stay a little mysterious. The best writing does. The words that click into place, wrap around something mysterious. They create a shape around which something lives—and they give hints about what that thing is, but do not reveal it fully. That’s the thing I want to do in my own writing: present words that act as a vessel for something more mysterious. I know it’s working when I feel like there’s something hovering beneath it the verbal, that mysterious emotional place.

Amy Tan, author of The Joy Luck Club, believes in the value of small details. She shared a writing exercise involving family photographs—a practice that inspired her new novel—and explains why she likes to move pixel by pixel.

I really admire the ACLU, and I value the important work they do. But I said, “You look at things universally, telescopically, macroscopically. I’m microscopic.” I’m at that tiny end where stories begin. I wouldn’t be able to say—it should always be this way, for all people. Generalizations are just not part of how I think. Stories begin with microscopic-level detail, in the particularities that make up each individual life. That’s my territory.

As I write a story, I have to be open to all the possibilities of what these characters are thinking and doing and what might apply. For me, the best way to do this is writing longhand, the way I write the early drafts of a novel. Writing by hand helps me remain open to all those particular circumstances, all those little details that add up to the truth.

So much of my work through the beginning—and especially through the middle—of writing a story is establishing what the characters believe as they go on and face ever-changing situations and hardships. Whether they fall in love, or have a death that occurs, or think that they’re dying—how do they respond, and what experiences shape the way they respond? I have to be open to their beliefs, whatever framework they might come up with to respond to the circumstances of their lives. As Whitman says, “Perhaps it is everywhere on water and on land”: I don’t try to confine myself to one particular road, but instead allow myself wide-ranging exploration.

There’s so much chaos in my early drafts. As I try to open myself up to all possibilities, anarchy tends to reign. So how do I know when I’m moving in a productive direction? If anything might happen in a character’s life, how do I determine which details will serve me well? I err on the side of going into too much detail when I do research and write. I abandon 95 percent of it. But I love it. It’s part of my writing process. I never consider it a waste of time….

I try to see as much as possible—in microscopic detail. I have an exercise that helps me with this, using old family photographs. I’ll blow an image up as much as I can, and work through it pixel by pixel. This isn’t the way we typically look at pictures—where we take in the whole gestalt, eyes focusing mostly on the central image. Ill start at, say, a corner, looking at every detail. And the strangest things happen: you end up noticing things you never would have noticed. Sometimes, I’ve discovered crucial, overlooked details that are important to my family’s story. This process is a metaphor for the way I work—it’s the same process of looking closely, looking carefully, looking in the unexpected places, and being receptive to what you find there.

Craig Nova, author of All the Dead Yale Men, offered advice from Robert Graves: “There is no good writing, only rewriting.” He explained how making radical changes—changing genre, voice, narrator, and so on—helps him learn about his subject and move towards a final draft.

Take point of view, for example. Let's say you are writing a scene in which a man and a woman are breaking up. They are doing this while they are having breakfast in their apartment. But the scene doesn't work. It is dull and flat.

Applying the [notion] mentioned above, the solution would be to change point of view. That is, if it is told from the man's point of view, change it to the woman's, and if that doesn't work, tell it from the point of view of the neighborhood, who is listening through the wall in the apartment next door, and if that doesn't work have this neighbor tell the story of the break up, as he hears it, to his girlfriend. And if that doesn't work tell it from the point of view of a burglar who is in the apartment, and who hid in a closet in the kitchen when the man and woman who are breaking up came in and started arguing.

It seems to me that each time you add a new point of view and tell the story again, you will discover something you didn't know before. And if this is true for point of view, it should hold true for structure, language, and all the other elements that go into a piece of fiction.

Finally, Elizabeth Gilbert disputed the idea that great art is rooted in suffering. For her, maintaining “stubborn gladness” helps her back away from self-hatred—and become a more productive, fulfilled artist.

Writing can be a very dramatic pursuit, full of catastrophes and disasters and emotion and attempts that fail. My path as a writer became much more smooth when I learned that, when things aren’t going well, to regard my struggles as curious, not tragic.

So, How do we get through this puzzle? That’s funny, I thought I could write this book and I can’t, instead of, I have to drink a bottle of gin before 11:00 to numb myself at how horrifying this is. You could almost call it a spiritual practice I’ve cultivated over the years. I really worked to create that kind of relationship—so that it’s not a chaotic fight. I don’t go up against my writing and come out bloody-knuckled. I don’t wrestle with the muse. I don’t argue. I try to get away from self-hatred, and competition, all those things that mark and mar so many writers’ careers and lives. I try to remain stubborn in my gladness.

We have this very German, romantic idea that if you’re not in pain, and if you’re not causing pain by making your art, then you’re not really doing it right. I’ve always questioned that … I mean, listen to the language we use to talk about creative process: “Open up your vein and bleed.” “Kill your darlings.” I always want to weep when people speak about a project and say: “I think I finally broke its back.” That is a really fucked-up relationship you have with your work! You’re trying to crack its spine? No wonder you’re so stressed out! You’ve made this into battlefield! We should know enough about the world to realize that anything that you fight fights you back.