In cutoff shorts and a hand-me-down T-shirt, I performed the dance moves 7-year-old me had choreographed to Tiffany's "I Think We're Alone Now." My mom and I were in the garage that my father had converted into a bedroom for his four youngest kids, and my mother was dutifully gagging as I lip-synced with fearless ineptitude for a solid four minutes. When the mini-cassette stopped in my little Fisher-Price Pocket Rocker, my mother applauded. "I think I want to be a singer," I told her. She smiled and told me I could do anything.

When I was young, I craved success and recognition because my family was relatively poor and there were so many of us. I'm the fifth of my parents' eight children, with four brothers and three sisters. Several years prior to that aforementioned Tiffany impression, when I was 3 or 4, I told my parents I was a boy. They disagreed. They dismissed me, and with damnation on the table — we were staunch Catholics — I conceded. It wasn't until I was an adult that I realized there was more to that conversation than my childish fancy. These days, I am aware of and incredibly comfortable with my very fluid gender identity and sexuality, and fortunate enough not to have to worry about it too much. I vacillate between feminine and masculine aesthetics, and not just in the way I dress, the way I keep my hair, and the way I do my makeup, but also in subtleties of presentation and body language. Sometimes I feel (and am) more toward one end of the gender spectrum than the other. Last year, when I wrote something on Tumblr about identifying as genderfluid, my father disowned me. I later forgave him of my own accord, but we haven't spoken since. I wonder sometimes if he would have been more or less understanding if it were one of my brothers that had come out as queer or trans.

Through a weird and winding road of events and circumstances, I ended up returning to my Tiffany-inspired dreams of singing after a brief dalliance with the violin. I've been writing, performing, recording, and touring my own music for about a decade now. I've toured solo, as a member of other people's bands, and most recently as the leader of my own band, Lower Dens. Often times I've toured as a woman, or at the very least been perceived as a woman by most of the people that I meet — genderfluidity doesn't necessarily mean I always go out of my way to hide the physical aspects of my body that people have long associated with womanhood.

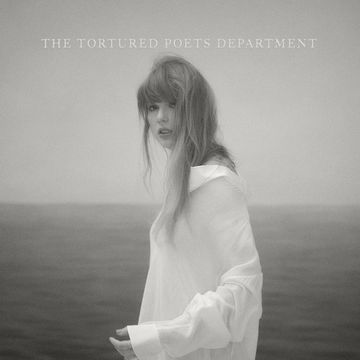

But because I don't think of myself as a woman, it's always been especially jarring and confusing when I come across run-of-the-mill misogyny on the road. Misogyny in the music industry is an oft-covered topic of late. Björk recently spoke about two-man duo Matmos having been repeatedly credited for songs she produced herself despite Matmos's insistence that it was Björk who deserved the applause. Grimes, an accomplished producer and songwriter, has written about amateur male musicians offering to "help her out," as if she's not perfectly capable of handling things on her own. Even someone as hugely famous as Taylor Swift has trouble convincing people that she writes her own songs, including her fellow musicians: When she collaborated with Imogen Heap on a track for 1989, Imogen said she had previously assumed that Taylor was "puppeteered by an aging gang of music executives."

This is something women and those identified as women, not to mention trans musicians and people of color, deal with constantly. For myself, I've learned not so much to fight it directly as to work around it, because I'd rather be making things than arguing. Let me paint a picture for those who aren't sure what I mean.

You are checking sound in any city, anywhere. The promoter starts asking your (male) bandmate questions. The bandmate looks at you. You answer. The promoter continues to face your bandmate as he asks questions. You sigh and continue to answer.

An unscrupulous friend texts you a screenshot of a comment thread wherein anonymous strangers are deciding whether or not you look fat to them. You delete the text.

You wake in the middle of the night to use the bathroom in the disgusting home you're crashing at on tour and are told by the strange man holding open his sleeping bag, "It's OK. Just get in." You say nothing, wake your bandmates, and shell out for a cheap hotel room.

Over the years, you get a creeping sensation — which eventually develops into a queasy feeling and then a simmering rage — that no, you're not crazy. Things really are harder and more repulsive than they should be, and yes, if people thought of you as man, it would be easier and you would probably be making at least some money.

And that is the thing that gets me, at least lately. That you have to talk yourself into believing that misogyny exists, even when the evidence is stacked up, even when you're banging your head into the wall over and over and over. Our insistence on valuing some humans above others is such an inscrutable quandary. Every day, all humans are judged and all humans are judging, but why do some get the benefit of the doubt? Why do we choose to rate people against each other based on such an arbitrary designation as gender when it's obvious this brings us nothing but grief? I don't want to believe the world is that way, and I don't want to believe I am subject to something so arbitrary, so false. It isn't that I feel sorry for myself; it's that I don't want to be disappointed in the world around me.

That's just me though. It's a luxury to be able to elude rather than be forced to fight. When it comes to other people getting stepped on, overlooked, over-tasked, underappreciated, I do not mind letting my blood boil. I think about my mom a lot. Cross her or anyone that remotely reminds me of her, and watch out. When I was singing for her in that carpeted garage all of those years ago, she'd already had eight children. She'd dropped out of college to be a wife and mother after graduating as the valedictorian of her high-school class. She knew as well as anybody what the odds were, what sacrifice meant, and how faith is sometimes all you have going for you, and despite all that, she still told me I could be anything I wanted to be. We've had our disagreements in the past, but ultimately my mother knows me as well as anyone, and her love for me is beyond questioning. Every day, no matter what comes and in full knowledge of the world I live in, I know my capabilities and myself. No matter what anybody else thinks, says, or does, thanks in large part to my mother, I am who I say I am.

Lower Dens' new album Escape From Evil is out now.