Two people in business suits sit chatting outside. Source: Francis Moran

When I recently read this fantastic article from Jamelle Bouie entitled Why Do Millenials Not Understand Racism?, I couldn’t help but think it didn’t go far enough.

As someone who works with young people all the time, I definitely see the patterns Bouie describes in his analysis of research done by MTV (yeah, MTV does research! Whodathunk?), but it’s just too simple to say that Millenials don’t understand racism.

I think a lot of millenials in general misunderstand the connection between systems of oppression and interpersonal experiences of prejudice, but this is also a race-specific problem.

And by race-specific, I mean that this is a White people problem more than anything.

Now, let me be clear about why this article is directed at White people.

First, I am White, and as such, my role in ending racial oppression must be in engaging other White people to join accountable work for racial justice. Plain and simple.

Second, because privilege conceals itself from those who have it and because White people benefit most from the current systems of racial oppression, we as White people have a particular tendency to bury our head in the sand on issues of race, but we also have a particular role in acting for racial justice.

Are there people of Color who act in ways that reinforce systems of racial oppression? Sure. But it is not my place to address those issues. It is my place to work with White folks.

Thus, inspired in part by 18 Things White People Should Know/Do Before Discussing Racism, I would posit that there are a few things that it’s about time all White people figured out.

These are things we’ve been told collectively by people of Color countless times, but we don’t seem to be hearing them. Perhaps we can hear them differently when called in by a White person to consider how we can actively work to end racial injustice and oppression.

1. Racial prejudice and racism are not the same thing.

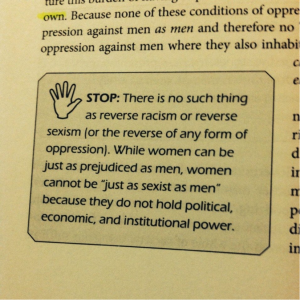

I recently posted the following graphic on Facebook:

Originally posted by Afropunk, though I’m not sure the original source.

(If you’re not sure why reverse racism isn’t a thing, that’s a wholly different article. Read this before continuing.)

It led to a frustrating and tense conversation with a White man who called it “the single dumbest thing [he’d] ever read.” I tried to unpack the “Prejudice + Power = Racism” argument, but it wasn’t working.

He kept coming back to something I often hear from White people when this notion of racism is presented.

He was very concerned about how this sentiment is unfair, as it seems to let women or people of Color or other oppressed people off the hook for prejudicial behavior.

Perhaps this speaks to how we as White people need to engage White folks differently in the conversation. Reverse racism is not real because racial prejudice directed at White people doesn’t have the weight of institutional oppression behind it, but that doesn’t meant that White people aren’t sometimes hurt by racial prejudice.

This is not to say that we should cater to White people’s feelings in conversations about racism or that this hurt is in any way comparable to the hurts caused by racism. It is to say, though, that we as White folks need to talk about this concept in a new way when engaging other White people.

If we never acknowledge the ways that White people feel wounded by interpersonal racial bigotry, we can’t push past this defensiveness to make change.

So no, it does not feel good to be called a “cracker.” It’s legitimate to feel hurt by that language. And as White folks, we can validate that hurt in other White people as we call them in to a conversation about racism.

It’s not legitimate, though, to equate that language with racist language that reinforces the oppression of people of Color. Sure, it can be a hurtful reaction, but equating racial prejudice against White folks with that experienced by people of Color erases the often-invisible structures of oppression at play, and doing so ensures that we never actually deal with root causes.

2. Interpersonal racism and systems of racial oppression rely on one another.

Race as we know it was created to ensure that poor Europeans utilize interpersonal expressions of racism to uphold bigger systems of oppression.

Thus, whether we’re talking lynchings or everyday microaggressions, the end result is the same: the actions taken by individuals further marginalize and devastate those already oppressed by racist structures like our educational system, our criminal injustice system, and so on.

Thus, while we absolutely must focus our energy on racist individuals or actions, it’s not simply for the sake of that individual or those they impact.

We must see engagement of interpersonal racism as a tool in the wider dismantling of racist structures.

3. Race isn’t real, but the impacts of race and racism are very real.

One of the more common responses that I hear from White people when confronted with the socially-constructed nature of race for the first time is for them to push a “race-neutral” ideology. This is often characterized by statements like, “But I don’t see race” or, “If race isn’t real, then we really are all one human family!”

The problem with this, though, is that despite race having no actual root in biology, race as a social construct and the subsequent racism are very real. Thus, “race-neutral” ideology is problematic for a few reasons.

First, it erases people of Color’s cultural experiences and the reality of their lives and the oppression they face. This can’t be stressed enough.

When you say that you “don’t see color” or “but we’re all one human family,” you are erasing people’s lives, cultures, and the oppression they face.

Second, it doesn’t actually help us to approach the problem in “race-neutral” ways because the problem isn’t neutral. The problem is one of racial hierarchy that privileges the lightest-skinned among us.

4. Yes, White people have a racial identity.

For many White people, particularly those who live in White-centric communities, we never have to consider our own racial identity.

I cannot tell you how many times I’ve heard White people called upon to describe their race only to have them say, “I’ve never really thought about it. I guess I’m just normal.” Hell, I’m pretty sure I was talking this way not too long ago.

The reality, though, is that White people do have a racial identity, and sadly, for much of recent history, our racial identity has been intrinsically tied to oppression. But recognizing that we have a racial identity allows us to do a few things.

First, it allows us to begin the process of being more accountable to others in the ways we benefit from racial oppression. Acknowledging that we, too, are racialized beings is literally the first step in acting for racial justice.

Second, acknowledging our racial identity allows us to begin working to cultivate a more anti-racist White identity (as described well in the scholarship of Janet Helms and Beverly Daniel Tatum’s racial identity development models). Being White doesn’t have to mean that we passively allow ourselves to be a tool of racial oppression. We have the power to build actively anti-racist racial identities.

Part of that process, then, is holding the tension of our Whiteness and our cultural and ethnic identity outside of being White. Doing so allows us to imagine ourselves as more than just “oppressors,” which opens up doors into anti-racist work.

5. Race cannot be divorced from other aspects of identity.

Our identities are complex, and while we may be racialized beings, we are also gendered beings and abled/disabled beings and beings with sexualities and more.

If we talk about our race in isolation, we can fall into a few troubling patterns.

Either we choose to play up other aspects of our identity to avoid accountability to our race (i.e. “I understand racial oppression because I’m oppressed as a White woman”), or we focus so intently on race that we don’t consider how our race is also informed by the other aspects of our identities.

In Mapping the Margins: Identity, Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color, Kimberly Crenshaw, originator of the term intersectionality, notes, “My focus on intersections of race and gender only highlights the need to account for multiple grounds of identity when considering how the social world is constructed.”

To pretend that White experience is monolithic doesn’t help us to bring White people into anti-racist struggle. After all, our experiences of being White are influenced by many other aspects of our identity.

A poor White person’s experience with race is not the same as a wealthy White person’s experience. A cisgender White person’s experience with race is not the same as a Transgender or non-binary person’s White person’s experience.

At the same time, we need to be careful not to let other aspects of our identity shield us from accountability for our Whiteness and our privilege, as doing so also doesn’t help us work for racial justice and only serves to reinforce our racialized privileges.

Simply put, intersectionality is vital to any movement for justice, and our racial identities must be considered in the context of other aspects of our identity.

6. Racism isn’t a partisan issue. It’s a White people issue.

Part of acknowledging that race has real impacts in our lives is taking responsibility for the subtle and overt ways that we may contribute to racial oppression. However, we as White folks like to simply point fingers, as it absolves us of doing the more difficult work of self-reflection.

Over and over we see partisan bickering over which party in the United States is, in fact, racist:

Let’s be clear, though. When it comes to maintaining systems of oppression, there’s been plenty of White bipartisan cooperation.

School-to-prison pipeline? Bipartisan. Expansion of racist criminal industrial complex? Bipartisan. Structuring of wealth to flow toward wealthy White people and away from everyone else? Bipartisan.

Why is this? Well, politics in the United States, whether advanced by Republicans or Democrats, have by and large created, reinforced, and entrenched White supremacy in our systems.

Thus, racism is a White people problem, not a partisan problem. Until we as White people understand our own investment in ending racial oppression, there will be plenty of people all across the political spectrum who will say and do racist things and, more dangerously, pass racist policies.

7. If we want to end racism, White people need to do more listening.

Something that often offends White people (especially since we can be socialized to believe we’re experts on anything and everything) is the idea that there are many, many things about race and racism in the United States that we inherently do not understand because we are White.

It’s impossible, though, for a White person to fully understand racial oppression because of the fact that White people do not experience racial oppression.

As noted above, White people can experience racial prejudice, but there is fundamentally much we cannot ever truly know about how racism operates in our society.

Thus, it is important for us to listen more. And when we listen, we need to trust the voices of people of Color who are telling us about the ways that racism impacts them, and we need to be careful not to just react defensively.

Let’s be clear, though, about what listening is not:

- Listening does not mean tokenizing a few people of Color for their experience. Instead, we need to listen to as many varied viewpoints as possible to better understand the complexity of racialized realities around us.

- Listening does not mean we expect people of Color to teach us. When people of Color choose to engage us or teach us, we should graciously listen, but we must not expect people of Color to be our educators on demand. Google is real, y’all.

- Listening does not mean demanding emotional energy from people of Color. Dealing with everyday racism is taxing enough without having White folks make emotional demands on the time and energies of people of Color or without White folks asking people of Color to take care of us when we’re having a hard time processing.

Authentic, non-defensive listening is key to all social justice work, but for people of racial privilege, there are few things that are more important.

8. White people need to engage White people in ending racism.

Because we cannot rely on people of Color to expend all emotional energy in being our teachers, we as White folks have a responsibility to engage other White people.

Honestly, I have a lot of growth to do in this area. It’s much easier for me to shake my damn head at the racist things White folks around me say rather than to do the hard work of calling them in to consider privilege and our role in reinforcing oppression.

But if all I ever do is shake my head, how am I really advancing the cause for racial justice?

In the end, my anti-racist work is only as good as my ability to engage other White folks in ending systems of oppression, for if White people do not divest from White supremacy, the road to racial justice is significantly harder for people of Color.

And if I’m going to do that, I have to express my love for my people by showing them the respect of calling them in and holding them and myself accountable to the work of building racial justice.

***

While these eight things are pretty darn important for White folks to know, this list is in no way exhaustive.

What would you add to the list?

Like this article? Then you won’t want to miss our new free workshop on “Healing from Toxic Whiteness to Better Fight for Racial Justice.” Join the other 5,000+ participants by signing up here!

[do_widget id=”text-101″]

Jamie Utt is a Contributing Writer at Everyday Feminism. He is the Founder and Director of Education at CivilSchools, a comprehensive bullying prevention program, a diversity and inclusion consultant, and sexual violence prevention educator based in Minneapolis, MN. He lives with his loving partner and his funtastic dog. He blogs weekly at Change from Within. Learn more about his work at his website here and follow him on Twitter @utt_jamie. Read his articles here and book him for speaking engagements here.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more