The gap between boys' and girls' respective reading abilities has been getting a lot of attention lately, but the trend itself is not new.

Girls have been better readers than boys for a long, long time, according to a report released Tuesday by the Brown Center on Education Policy at the Brookings Institution. The annual report analyzes three topics in contemporary education through the lens of up-to-date research. This year, the report looked at the effectiveness of the Common Core state standards, the relationship between student engagement and academic achievement, and the gender gap in reading.

Below are three key insights into gender gaps the report provided:

1. These Gaps Have Existed For A While, But They Might Closing

When the first National Assessment of Educational Progress was given to students in 1971, girls significantly outperformed boys on reading. Since then, girls have continued to outperform boys in this area, although the gap has gotten smaller, as shown in the graph below. Both male and female students have made gains in their NAEP scores over the years, but recently boys have made bigger gains, the report found.

Notably, gender gaps in NAEP reading scores are not as big as gaps between other groups of students. The gap is much, much bigger between low-income and affluent students (with affluent students attaining higher scores). The gap between black and white students -- with white students attaining higher scores -- is also significant.

2. It's A Global Problem

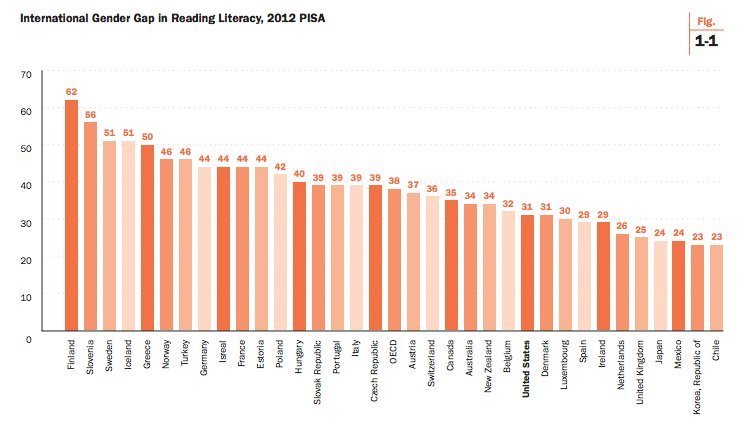

Gender gaps in reading scores are not unique to America. Scores on the Programme for International Student Assessment, an exam taken by 15-year-olds, indicate that the same phenomenon is occurring internationally.

Some countries have larger gaps than others, as shown in the graph below of PISA score disparities. Most notable is the gap in Finland's scores.

Given that Finland is often lauded for its especially high PISA scores, the report said this gap is potentially troubling. Finland's dominant PISA scores can be attributed entirely to over-performing girls, as Finnish boys tend to perform at the international average in reading.

From the report:

"That's the headline story here, and it contains a lesson for cautiously interpreting international test scores," wrote Tom Loveless, author of the report, who is a senior fellow at Brookings. "Think of all the commentators who cite Finland to promote particular policies ... Have you ever read a warning that even if those policies contribute to Finland's high PISA scores -- which the advocates assume but serious policy scholars know to be unproven -- the policies also may be having a negative effect on the 50 percent of Finland's school population that happens to be male?"

However, evidence from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, the group that distributes PISA, suggests that this literacy gap closes for boys by the time they reach adulthood.

"On average among 16-29 year-olds, young women outperform young men in literacy by an average of one score point -- meaning that there is, effectively, no gender difference in literacy proficiency," said an OECD report released in March.

3. Enjoyment Of Reading Has Nothing To Do With It

In addition to measuring students' reading abilities, PISA asks students how much they enjoy reading. Unsurprisingly, girls reported an affinity for reading more often than boys did.

However, reading enjoyment may not have a role in girls' higher proficiency. Between the years of 2000 and 2009, when boys reported increased enjoyment of reading, that did not necessarily translate to higher PISA scores in many countries.

The reasons for the gender gap in reading are still unknown, the report noted, and it is unclear whether the gap is a function of biology, cultural influences or school practices.

"The universality of the gap certainly supports the argument that it originates in biological or developmental differences between the two sexes," the report said. "But some of the data examined above also argue against the developmental explanation. The gap has been shrinking on NAEP. At age nine, it is less than half of what it was forty years ago. Biology doesn't change that fast."