Newsroom Diversity: A Casualty of Journalism's Financial Crisis

New numbers from the American Society of News Editors show that the progress of women and minorities in media has halted.

The American Society of News Editors (ASNE) recently released its annual study of newsroom diversity. The results only confirmed what many who have lived through the industry's deep recession have already experienced: a steady decline in minority journalists and stagnation in prior progress. Despite claims by news organizations that they value and promote diversity, the numbers in this year's study show 90 percent of newsroom supervisors from participating news organizations were white.

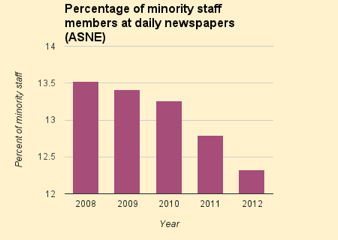

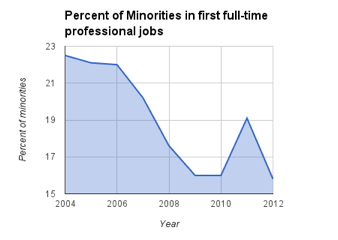

At a time when non-whites make up roughly 37 percent of the U.S. population, the percentage of minorities in the newsroom has fallen to 12.37 percent from its 13.73 percent high in 2006. According to last year's 2012 ASNE study, overall newsroom employment at daily newspapers dropped 2.4 percent in 2011, but the picture looked much worse -- down 5.7 percent -- for minorities.*

This means that fewer minorities are getting the opportunity to work in news, and news organizations are losing their ability to empower, represent, and -- especially in cases where language ability is crucial -- even to report on minority populations in their communities.

Why have minorities been disproportionately hit by the state of the media industry? Two dozen industry leaders I talked to in recent months point to a series of mostly cost-saving decisions at papers across the country that had unintended consequences.

One piece of this puzzle is layoff policies and union contracts that often rewarded seniority and pushed the most recent hires to leave first. Many journalists of color have the least protected jobs because they're the least senior employees, says Doris Truong, a Washington Post editor and acting president of Unity, an umbrella group of minority journalist organizations.

At papers like The Washington Post, which has had five rounds of buyouts since 2003, "You could see the writing on the wall: you take the buyout today, or face the layoff tomorrow," Woods says.

Any attempts that might otherwise be made to remedy the problem have taken a backseat to economic concerns. Newspaper advertising revenues are less than half of what they were in 2006, and papers once accustomed to healthy profit margins struggle to stay afloat. Journalist Sally Lehrman, a professor at Santa Clara University, says she has heard a news executive say that "wondering about diverse voices and perspectives is a bit like wondering about the fate of Mrs. Gardner's rose garden after a tornado has decimated the entire village."

The result is that Dori Maynard, president of the Robert C. Maynard Institute for Journalism Education, says she has watched journalists of color leave newsrooms at an alarming rate, even as the audience consuming news has grown more diverse. "The news media and the nation are moving in two different directions," she says. "News media is getting whiter as the country is getting browner." Journalists of color "feel their voice is not heard, their story ideas are not validated, and they don't see room for advancement."

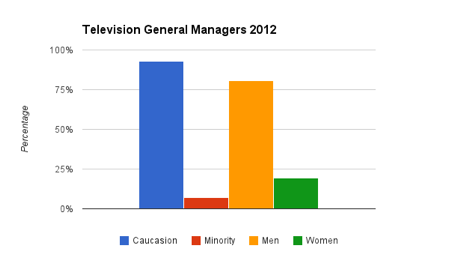

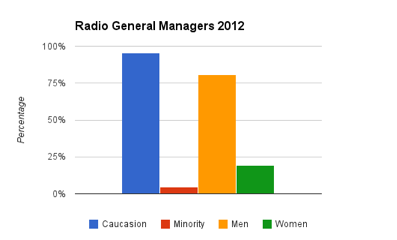

With notable exceptions, minority journalists remain even more under-represented in leadership positions across newspapers and the broadcast news industry than in the newsroom in general. Particularly in broadcast, "the higher you get, the whiter it gets," says Felix Gutierrez, professor of journalism and American studies & ethnicity at the University of Southern California. The Radio Television Digital News Association (RTDNA)'s 2012 diversity study reports that 86 percent of television news directors and 91.3 percent of radio news directors are Caucasian.

Benet Wilson, who chairs the National Association of Black Journalists (NABJ) digital task force, believes the issue of minority representation is exacerbated by a loss of diversity leaders. As senior diversity champions have left newsrooms, she explains, the minorities who stay have felt they have no voice at the top.

There's "a loss of management, a loss of older reporters, a loss of diversity champions -- people who had the title officially or unofficially," says Wilson, who left Aviation Week in 2011 and now works for the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association.

The consequences have been less diversity advocacy around issues of training, media partnerships and community coverage, she says. "You've got to cut somewhere, and you cut where there is the least amount of squawking. There's no one left to say, 'you can't do this.' The stone starts rolling down the hill, and you can't stop it."

Diversity efforts, Woods adds, generally "resided in an individual who left, got reassigned, retired, or who was laid off." In other cases, diversity was part of a specific outreach initiative that ended with the loss of a grant or project.

Minority journalist conferences, once a key source of revenue for diversity projects and a major recruiting tool for newspapers, have plummeted in attendance. Luther Jackson, former executive officer for the San Jose Newspaper Guild, remembers strong partnerships between newspapers and minority journalist associations starting in the 1980s, which began to taper off in 2001.

The Business Case

The problem, fundamentally, has been reconciling diversity with newsroom business models. "Most media companies look at diversity as a cost center," says Paul Cheung, President of the Asian American Journalists Association. "They see it as something nice to do." Few, he says, actually connect the dots and make it into a business case.

Cheung believes this has contributed to the industry's financial losses. Diversity is not just "a nice thing to have--it's crucial for a company's survival in the future," he says. "More than 50 percent of Americans by 2050 will be non-Caucasian."

Why does it matter, from the business perspective, if newsrooms don't reflect society at large? Because publications need readers. Robert Hernandez, assistant professor of journalism at the University of Southern California, attributes a decline in reader engagement to the fact that so many people don't see themselves reflected in coverage. "When I left The Seattle Times, I was the last Spanish speaker on staff," he says. "There would be crime stories-- and I'm the web guy-- and they called me over to translate interviews in Spanish."

Radio, Television, and Online News

The broadcasting industry has faced similar challenges. The Radio and Television Digital News Association (RTDNA) reports that in the last 22 years, the minority population in the U.S. has risen 10.4 percent, while the minority workforce in television news is up only 3.7 percent, and the minority workforce in radio is up 0.9 percent.

"Broadcast was kind of a leading edge of major social changes taking place in the country," says Bob Papper, who has overseen the RTDNA study for 19 years. "What television stations learned over time is if you want to appeal to the audience in your market, you need to look like your audience." Broadcast diversity figures have held relatively steady over the last few years as radio has seen much lower figures.

But overall, Papper says, "the minority population in this country is growing about 3/10th of a percent a year. If you hold steady, then every year you're falling behind."

On the positive side, the digital landscape has opened up new channels for a wide variety of people to produce and consume news. "There are now so many websites and community sites that let you get closer to subjects that interest you," says Jim Brady, Editor-in-Chief at Digital First Media and President of the Online News Association. "Everyone has an opportunity to zone in on their interests in a way that didn't exist when 200 news organizations drove the conversation."

While established newspapers once had the power to serve as gatekeepers, now anyone who can pay for a data plan and WordPress account can write about an area of interest, he says.

Mark Luckie, Manager of Journalism and News at Twitter, says with social media "it's less about who you are but 'are you bringing value to the conversation?'"

Sree Sreenivasan, Chief Digital Officer at Columbia University, says African Americans and Indonesians often play the biggest roles in setting trends on Twitter.

With the rise of smartphones in many communities, everyone has a newsgathering tool in their pocket, Brady says, and mobile has brought down cost needed to give oneself a digital presence. Pew studies suggest that mobile penetration is indeed increasing, particularly in Hispanic and African American communities.

But many are skeptical about diversity in web 2.0 culture. "Online news gives everyone a chance to work in news, but the issue is how do you get paid?" asks Doris Truong, president of Unity, an umbrella organization of minority journalists.

"Very few people have had access or desire to have training as a reporter, journalist, critical thinker," says Danyel Smith, a writer, editor, and Knight Fellow at Stanford University. "Just because there's Tumblr, WordPress, and Twitter in terms of instant publishing, doesn't mean these populations are much better served to the degree they can and should be."

The idea that the Internet has made the news more diverse "is a bit of a trap," agrees Lehrman, the Santa Clara University professor. While journalists once felt responsible for creating diverse public spaces and forums, today, she contends, journalists sometimes assume people create them for themselves and don't attempt proper civic debate.

"Digital tools increasingly narrow the scope of information you have access to unless you deliberately push it open," says Lehrman.

Search engines, for instance, have changed news consumption patterns in ways that can filter out these more diverse outlets. Customized news, she says, "is a force against this kind of digital diversity." Google's algorithms, in her view, work against broadening the spectrum of voices people access and hear daily.

In some ways, Internet news "allows us to dig deeper into our silos and become less informed about communities outside our own," says Maynard.

The staff behind new online publications has also caused many diversity champions to pause. "The online pioneers looked very much like the traditional Old White Boy's club," says Juana Summers, a Politico reporter and member of the board of directors at the Online News Association.

"It gets back to the networks by which people get funding and attention for projects. They're historically a lot stronger, in journalism and venture capital, among white men," says Lehrman. "If you went to a few ONA conferences, initially, it was like a sea of white faces."

ONA has devoted considerable efforts to diversifying its panels and leadership in the last year as a result.

"I think part of it is that with online news, there is so much opportunity but it takes a whole lot of risk," says Summers. Minorities, particularly those with less financial security, may find it very hard to jump into a web startup than traditional companies with 401ks. "I'm dealing with students a lot, women who are often new to the field and that may prove a barrier to entry," she says.

Summers, 24, understands the hesitation on a personal level. "As someone who grew up in a lower-middle class family, paycheck to paycheck, it was a very hard risk to take to take a chance at a startup, knowing I might not have a job in three to six months. I'm black, from a single parent family. That's a tough sell to make," she recalls.

Unpaid internships compound diversity concerns by reserving entry-level journalism positions to financially advantaged youth who can afford to work for free.

Woods says the roots of inequality in digital journalism are different from those in traditional media. "Back when we began fighting for change, the foe was malevolent exclusion. It was a society that segregated and separated and believed in superiority and inferiority," he says. "When dotcom news organizations popped up, what you had was a bunch of people using their savings, retirement plans, or investments of their own money, who got together with friends who also had money and created organizations because damned if they'd be driven out of the business."

In short, he says, "I do not believe it has the [same] roots in exclusion our industry's history would have, but the result looks exactly the same."

In terms of digital skills, minorities may also lose out due to training issues. People who have more established job and are better connected within the political hierarchy of the news organization have more access to training.

"When I started as a journalist, I started on a typewriter," Wilson recalls. "You need to network and be in with the people revolutionizing." In this sense, she says, minorities are sometimes at a disadvantage. "My newsroom went digital in 2006, and until I got laid off I was waiting for that training."

In some cases, especially with relatively young institutions, the question of diversity in digital newsrooms may have simply not come up. "When I talk to people about diversity in the news, it's often seen as an old idea," says Lehrman.

Just how fast digital newsrooms are making diversity a priority can be almost impossible to measure. Professor Adam Maksl, who analyses data for the ASNE diversity study, believes the institution of journalism should be more diverse. "What's difficult is we don't know what the institution of journalism is anymore," he says. With online news, Maksl explains, there is no list of all the online news sources, or even a clear definition of what constitutes an online news organization.

But despite these challenges, dedicated diversity leaders are still working to try to insert diversity back into the agenda at newsrooms across the country, digital or otherwise.

"The news media is not only failing to serve the communities but the country at large when they fail to reflect what's going on in communities of color," says Maynard. This lack of diversity in newsroom employment shapes news coverage regardless of the medium. Looking at news today, she says, "African Americans are in stories about crime, sports, entertainment. Latinos in immigration. Native Americans and Asian Americans apparently don't contribute to the fabric of our lives."

For Woods, "when you fail to pursue the most diverse news staff, you fail to open up the possibilities created when you bring a broader range of life experience, insight, understanding, curiosity-- all the things that go into creating story ideas and coverage plans, and all the things that bring us news."

* This sentence has been edited for clarity.