Story highlights

Amid civil war, al Qaeda affiliates are fighting more moderate rebels in north Syria

Governments of Turkey and Iraq, and the Kurds of northern Iraq, have interests and allies there

Kurdish group has declared an autonomous region, drawing criticism from other rebels

Area villages, border crossings change hands, and alliances shift, complicating peace efforts

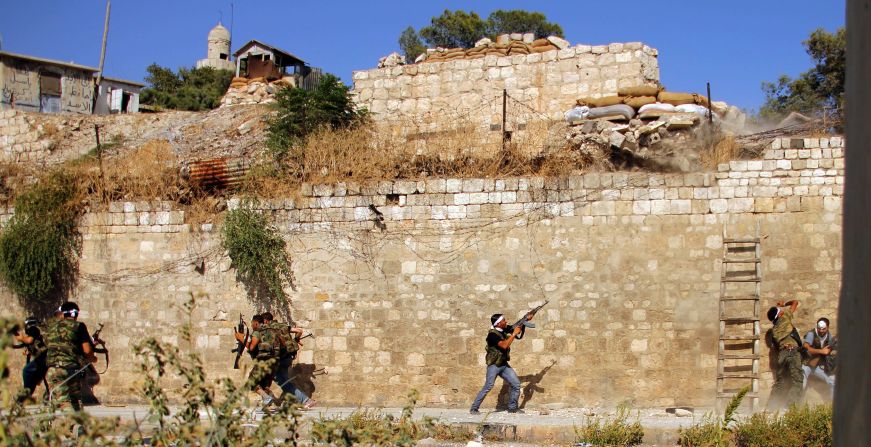

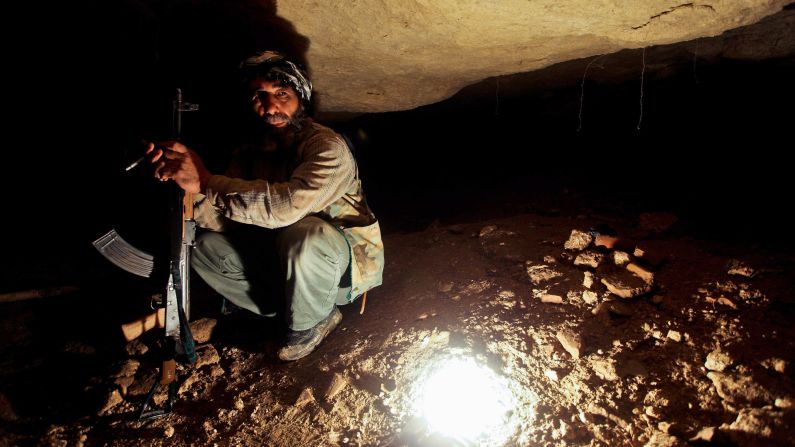

While the world has been focused on eliminating Syria’s chemical weapons, a vicious war within a war has gained momentum in northern Syria. It is a complex conflict that pits al Qaeda affiliates against more moderate rebel factions and against Syria’s 2-million strong Kurdish minority. But it also threatens to spill far beyond Syria’s borders.

The largest Kurdish group – the Democratic Union Party (PYD) – raised the stakes last week by declaring the autonomous region of “western Kurdistan” in a part of Syria that normally produces about one-third of the country’s oil.

Other rebel factions condemned the move as a step toward a declaration of independence and the breakup of Syria. The opposition Syrian National Council said the PYD and its allies represented “a separatist movement, disavowing any relationship between themselves and the Syrian people, who are struggling for a united nation independent and free from tyranny.”

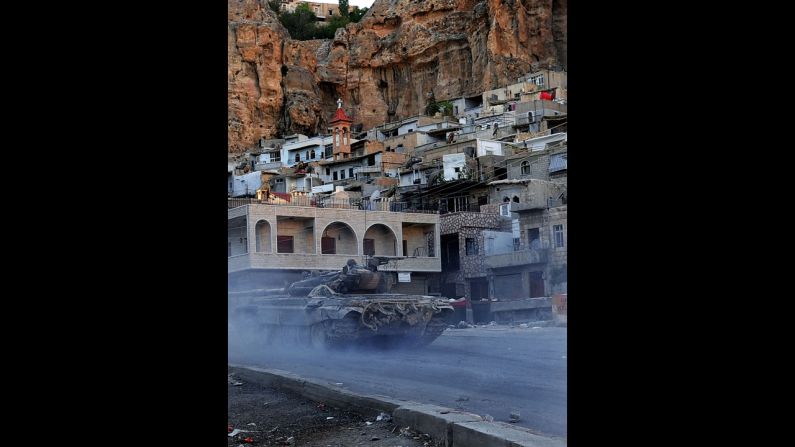

What happens in this region is of acute concern to the governments of Turkey and Iraq, and to the Kurds of northern Iraq, all of which have their own interests and allies there. For the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, Kurdish success at the expense of the Free Syrian Army and Islamists is the least worst outcome, dividing the opposition and depriving its main adversaries of an operational hinterland. The government retains military outposts in places like Qamishli, the largest Kurdish city, in what appears to be a tacit understanding with the Kurds.

Northern Syria has now become a patchwork of fiefdoms, with villages and border crossings changing hands and shifting alliances among opposition groups: yet another obstacle for the United States and other countries trying to kick-start a political process in Syria. The PYD is demanding its own place at the table in any peace negotiations as the Kurds’ representative.

A growing threat from ISIS

On the battlefield, the PYD has focused its firepower on the al Qaeda-affiliated Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIS), driving it out of several border villages and taking control of areas along the Syrian border with Iraq. Kurdish “popular protection units” now control the crossing into Iraq at Yarubiya, potentially giving the Kurds an opportunity to export oil and gain revenue. The crossing is on the main highway to Mosul and Baghdad.

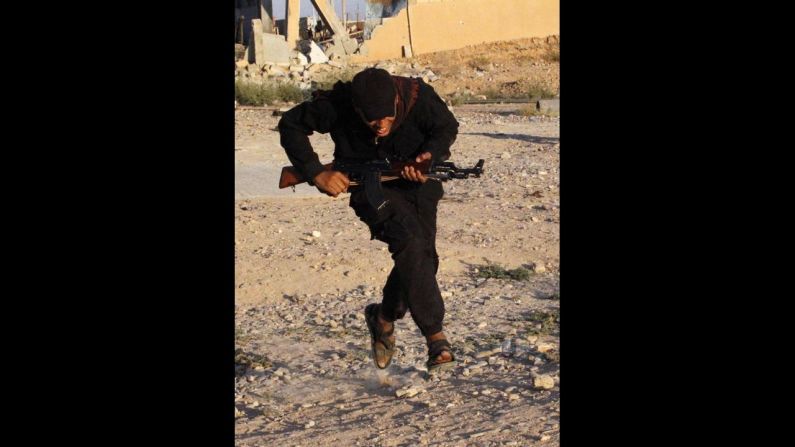

ISIS is far from down and out, however. It has vastly expanded its presence in northern Syria this year thanks to an influx of hundreds of foreign fighters. In October, ISIS seized the town of Azaz on the Syrian-Turkish border after heavy clashes with the Free Syrian Army’s Northern Storm Brigade. It accused the brigade of being in league with Kurdish “separatists” and warned the Free Syrian Army “not to be dragged into what is planned by them for the enemies who plot day and night, and seek by all means to pit these factions and the Islamic State against one another.”

ISIS also seized the Bab al Hawa crossing on the Turkish border from an FSA brigade, giving it the ability to bring in weapons and other supplies.

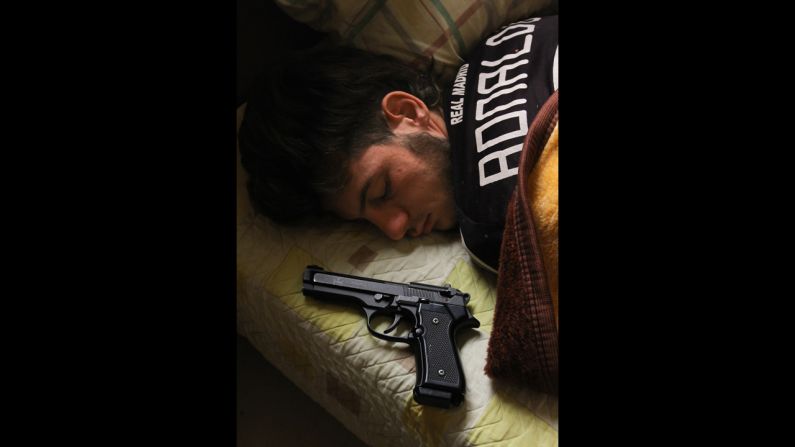

ISIS has gained a gruesome reputation for torturing and murdering prisoners taken during clashes with other rebel factions. A video posted by the Syrian Observatory on Saturday showed several FSA fighters who had been tortured and killed; the mediator sent to negotiate for their release was also reportedly murdered.

Joshua Landis, director of the Center for Middle East Studies at the University of Oklahoma, writes that according to one former prisoner, the ISIS “emir” in Azaz is a 16-year-old who has personally taken part in the torture of captives.

Recognizing the growing threat from ISIS, the Syrian National Council has accused it of “aggression towards Syrian revolutionary forces and indifference to the lives of the Syrian people.”

Islamist groups form alliance

Another al Qaeda affiliate, the al Nusra Front, is also involved in this mosaic of conflict. It has been trying to take control of areas north and east of Aleppo, Syria’s largest city, attacking Kurdish villages in the process. But al Nusra and ISIS appear to loathe each other as much as they do the non-Islamist rebel groups.

Landis, who runs the blog Syria Comment, says al Nusra and another Islamist group, Ahrar al-Sham, “are working together more closely than ever both to counter ISIS and to take power from weaker factions of the Free Syria Army.”

It’s another sign that the Syrian opposition continues to fracture on the battlefield but also that al Nusra needs allies as it seeks to take on ISIS and the Kurds.

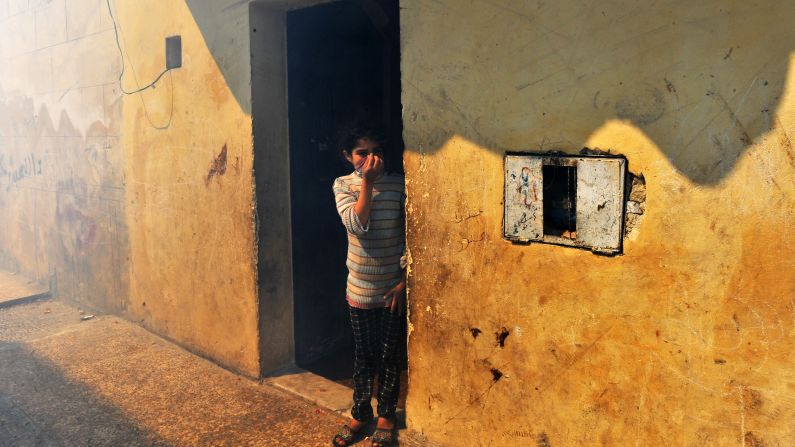

Kurdish militias, in turn, have evicted al Nusra from several villages along the Turkish border in recent weeks. But human rights activists claim the Kurds have also targeted Arab villages. At a local level at least, ethnic cleansing appears to be redrawing the map of northern Syria.

The PYD insists it does not want to see the breakup of Syria, nor ethnic conflict. But as in Iraq 10 years ago, the Kurds in Syria sense an opportunity to right old wrongs, and especially reverse the Arabization of Kurdish areas decreed by Bashar al Assad’s father. In the 1970s, Hafez al Assad essentially rendered the Kurds stateless and encouraged Arabs to settle in areas bordering Turkey, such as Hasakah province. About 60,000 Kurds were displaced in the process.

Writing in the current edition of the Combating Terrorism Center’s Sentinel, Nicholas Heras says “Hasakah presents a complex human terrain where conflict is driven by the patchwork authority of the Syrian military and local and long-standing communal antagonism. … Hasakah’s oil resources are also important and a source of frequent conflict between Arab and Kurdish armed groups. “

Heras sees an opportunity for the Kurdish militia in Hasakah province, if it protects minorities there. But it will, he writes, “need to continue to demonstrate battlefield successes against its antagonists, primarily Sunni armed groups such as the Salafi-jihadi organizations and tribal militias.”

Al Qaeda-linked group strengthens hold in northern Syria

Spillover into Turkey, northern Iraq

Turkey is already seeing fighting between the Kurds and other groups spill into its territory, with errant rocket fire killing several Turkish civilians over the past few months. Turkish forces have responded with howitzers, and Turkish authorities have begun building a border wall in several areas along the 820-kilometer (510-mile) border with Syria.

Ankara doesn’t want to see either al Qaeda or the Kurds prevail in northern Syria. Beset with its own Kurdish problem, it has no desire to see the PYD emerge as the dominant player. The PYD has long been an ally of the Kurdish Workers’ Party (PKK) in Turkey, which has fought a guerrilla war against the Turkish state for nearly 30 years. There is now a fragile truce while negotiations on a political settlement stutter on, but should those negotiations fail, the PKK could use Syria’s implosion to its advantage. Activists in northern Syria say hundreds of PKK fighters have already crossed the border.

The Turkish government has tentatively reached out to the PYD, whose leader Saleh Muslim Mohammed visited Ankara in July. But in subsequent interviews, he has accused Turkey of helping other Kurdish groups against the PYD and allowing Islamist militants to cross from Turkey into Syria, accusations denied by Ankara.

Muslim told Reuters this weekend that the Turks “are trying to divide the Kurds by bringing certain (Kurdish) parties into the Syrian National Coalition.”

The Kurds of northern Iraq have also been pulled into Syria’s war, not least because the fighting has pushed tens of thousands of Syrian Kurds across the border. There were just under 200,000 Syrians registered in refugee camps in northern Iraq in late October, according to UNICEF, the great majority of them Kurds.

The support of the Kurdish regional government for brethren over the border has brought a swift response from al Qaeda, which carried out two suicide bomb attacks in the Iraqi-Kurdish capital, Erbil, in September, killing several people. The Iraqi Kurdish leader, Masoud Barzani, responded by warning: “We will not hesitate in directing strikes (against) the terrorist criminals in any place.”

But at the same time, Barzani is wary of the PYD’s ambitions and has been trying to unite other Kurdish groups as a counterweight against it. Barzani has invested heavily in a good working relationship with Turkey – seeing it as a route for exporting oil from northern Iraq – and has no desire to see the PYD provoke Ankara. After its declaration of autonomy, Barzani accused the PYD of being in league with al Assad and of wrecking a golden opportunity for Kurdish unity in Syria. He was in the Turkish city of Diyarbakir on Saturday to meet Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan and back his negotiations with Turkey’s Kurds.

The Shia-dominated Iraqi government in Baghdad has other concerns, especially about al Qaeda’s new freedom of action in Syria. The scale and frequency of al Qaeda attacks inside Iraq have increased, with the violence there now at its worst since 2007. ISIS now has a rear base in northern Syria from which to plan attacks in Iraq, and it may have the support or at least tolerance of several powerful Sunni tribes that straddle the border.

Whatever happens around Damascus and in other theaters in Syria, the northeast threatens to become a vortex of conflict into which different Syrian groups, foreign fighters and outside powers are inexorably dragged.