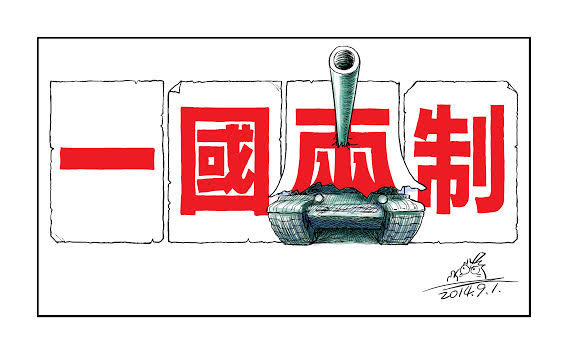

Biantailajiao's award-winning political cartoon about the White Paper issued by the Chinese government's State Council on “one country, two systems.” People in Hong Kong believe that the new interpretation of “one country, two systems” will ruin the city's autonomy. Used with permission.

Below is an interview with Biantailajiao, a mainland Chinese political cartoonist who recently won the Best Political Cartoon in Hong Kong In-Media's E-Citizen Awards, which aim to promote original reporting, political cartoons, photography and commentary online. The interview was originally written in Chinese by Oiwan Lam and translated into English by Jennifer Cheung.

“I never thought I could win this award, especially when I saw so many excellent creations at the Occupy Central sites. I felt a little ashamed,” says Biantailajiao humbly. He won the Best Political Cartoon in Hong Kong In-Media’s E-Citizen Awards this year.

Biantailajiao's profile picture in social media. Use with permission.

Biantailajiao, which means Metamorphosis Chili, is the pseudonym of Wang Liming, a mainland China-based political cartoonist. During his honeymoon in Japan, he was criticised by a number of state-run media outlets in China and labelled a “pro-Japanese traitor”. He decided to stay abroad and now lives in Japan as a university researcher. He hopes to travel to Hong Kong to receive the award and observe the creative political expressions at the sites of the so-called Umbrella Revolution there.

He used to draw cartoons for iSun Affairs Magazine, an independent publication focused on greater Chinese communities, but the magazine was shuttered in 2013. Compared to other mainland netizens, Biantailajiao pays close attention to the political affairs of Hong Kong, a special administrative region of China, and Taiwan, whose independence as a country China rejects. He believes the democratic future of these two places will serve as examples for the mainland. Although Hong Kong doesn’t have democracy, the citizens’ determination in the pursuit of democracy excites him. In contrast, in mainland China, many people defend the communist party’s totalitarian rule, which leaves citizens hopeless.

An recent example of intellectuals protecting Chinese authoritarianism came during a literature forum in October, when Chinese President Xi Jinping praised young writer Zhou Xiaoping for spreading “positive energy” on the Internet. Mainland netizens have largely debunked Zhou's work as “full of lies”. In fact, famous blogger Fang Zhouzi, who is a skilled fact-checker, was kicked off popular Chinese microblogging site Sina Weibo for his criticism of Zhou. Biantailajiao created a figurative caricature of the incident; netizens who retweeted the cartoon were questioned by police.

Biantailajiao points out that since Xi took office, Chinese citizens have enjoyed less freedom of expression. In October 2013, when the Central Propaganda Department cracked down on Weibo's opinion leaders, he received a subpoena from police accusing him of “spreading false information”. During the interrogation, the officers cautioned him to be careful, given that he had hundreds of thousands Weibo followers at the time.

Facing such pressure, Biantailajiao and other online opinion leaders have acted more cautiously since November 2013. Following the questioning, he limited his drawings to social problems that didn’t criticise the communist regime. Instead, he put his energy into a Taobao online store selling snacks from Japan and Taiwan that he operated with his friends. He never imagined that in May, when he was on honeymoon with his wife in Japan and collecting items for his Taobao store, that mainland authorities would level accusations of being a “pro-Japanese traitor” against him.

His accounts on Sina Weibo and Tencent Weibo, a similar service, were later deleted, and his Taobao shop was closed (later re-opened), cutting off a major source of income. On 9 August, he described the episode in a tweet as “the worst censorship” he had ever experienced.

Some speculated that the move was a retaliation against his satirical cartoon on Hong Kong's Occupy Central protests, a massive movement calling on the Hong Kong and mainland Chinese governments to allow genuine democratic elections. On 17 August, he published a cartoon that featured a mainland delegate going to Hong Kong to denounce Occupy Central and implied that mainland Chinese authorities mobilized anti-Occupy Central protests from behind the scenes. The next day, dozens of official mainland media outlets republished an article titled “See Through the Pro-Japanese Traitor Face of Biantailajiao”.

He felt wronged. “I have been very careful not to talk about politics and any topics related to Sino-Japan relations. I only wrote about people and things I appreciate, but for that I was labelled as a traitor”, he says.

A political accusation like that worries him a lot. He believes his suppression has nothing to do with him being “pro-Japanese”, but due to his drawings criticising Xi Jinping and supporting Occupy Central. As the attack he faced came from both online and print media, such coordinated moves convinced him that it was an “unified deployment from inside the party”. He was afraid he might be further persecuted when he returned to China. Eventually, with the help of a Japanese friend, he found a two-year unpaid research position at a university and decided to remain in Japan.

‘Irony and satire can also help citizens disperse their inner fear’

Political cartoons are a low-income, high-risk venture in mainland China. How did Biantailajiao step into profession of no return?

He says he began drawing comics when he was young. In the beginning, he drew love stories like other cartoon fans. But in 2006, when he signed up for “Mop hodgepodge”, a popular mainland forum on social affairs, he started using simple drawings to respond to social problems and gradually branched out into political cartoons.

Earlier, he worked in the advertising industry. In 2009, he began using the pseudonym Biantailajiao to publish his political cartoons on Weibo. At that time, he idolized the opinion leaders, or the so-called “big Vs” on Weibo. However, since there are not many political cartoonists who dare criticise the government, he quickly became a big V himself and embraced hundreds of thousands of followers, which surprised him.

Living in an authoritarian society gives Biantailajiao endless inspiration: “In this society bizarre things happen every day. You can simply retell these stories in the form of cartoon, then the cartoon will carry a sense of absurdity.”

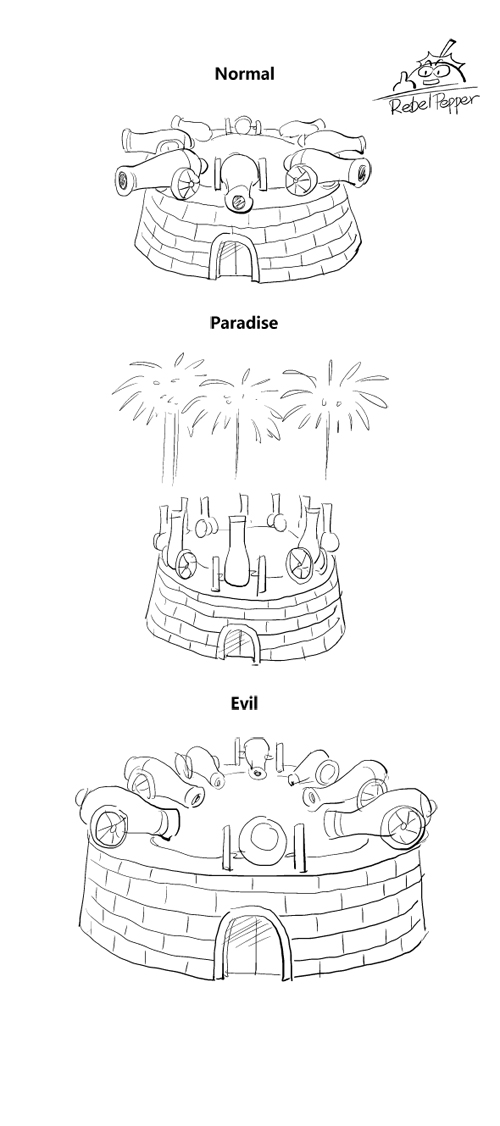

One of Biantailajiao's favorite political cartoons.

Of course, Biantailajiao has had to self-censor his drawings. Yet the euphemistic expressions he adopts can have wider appeal, and have become part of his unique style. One of his favorite cartoons uses three fortresses to represent three different types of countries: the normal one has its guns pointed outward, the ideal one has its guns pointed at the sky, and the evil one has its guns pointed inward. Everyone who reads the cartoon knows which country the cartoon is mocking.

“Humour is a sharp weapon challenging an authoritarian regime. The dictators have no sense of humour. Irony and satire can also help citizens disperse their inner fear”, Biantailajiao says, an opinion formed after many years of drawing cartoons under pressure in mainland China.

However, apart from facing political repression, drawing political cartoons in mainland China has also alienated him from some of his family and friends. His income has not been stable, either.

In 2011, he left the advertising industry and freelanced illustrations for various publishing houses. He also managed social media accounts for some companies. By working this way, he could have more time to publish his political cartoons on Weibo.

Since leaving China, he can enjoy the freedom to draw cartoons and express what is on his mind. However, he now faces new dilemmas too. Many mainland netizens have begun asking him to self-censor his cartoons because if they are too explicit and too critical, netizens who retweet them will be harassed by the police. Recently, a friend was questioned by the police after he retweeted a cartoon by Biantailajiao that mocked President Xi Jinping and writer Zhou Xiaoping. “In the future, I still need to practice self-censorship to make my cartoons subtle so that my work can continue to be circulated on China’s social media”, Biantailajiao says in frustration.

His readers have always been mainland friends and fans. Now that he has left the country, it is likely that in the future, he will need to draw cartoons that address Sino-Japanese relations for his career to take root in Japan.

1 comment

Don’t think Japan will like it either, especially with Abe Administration